|

Annie Gérin

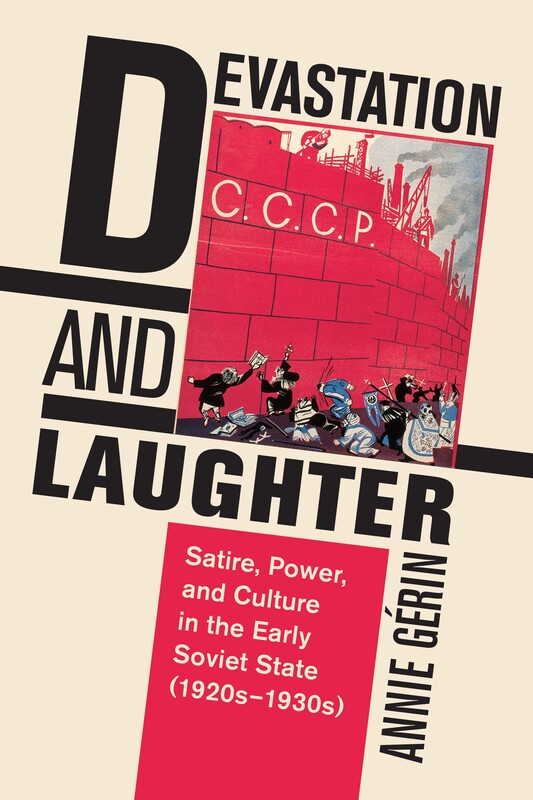

Devastation and Laughter: Satire, Power, and Culture in the Early Soviet State, 1920-1930s Toronto; London; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 2018 288 pp. 10 colour and 62 b/w illus. $82.00 (cloth) ISBN 9781487502430 With the 2017 centennial celebration of Bolshevik revolution, a flock of new studies dedicated to Soviet visual culture and propaganda have come to light, many of them accompanied by exhibitions (Revolution Every Day: A Calendar; Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1932; Rouge).[1] Among these, Annie Gérin’s book aims at a reevaluation of the place of laughter (smekh) in Russian culture in the 1920s and 1930s. Mainly envisioned as a weapon (oruzhie) in an ideological struggle, and as a tool (orudie) in the redaction of a new Socialist narrative, laughter is described in this study as a very serious affair, as a matter of state. For instance, some satirical posters of the Civil War bore warnings such as “anyone who tears down this poster or covers it up is performing a counter-revolutionary act” (50); a dominant and successful satirical journal like Krokodil (1922–2000) would regularly receive, between the 1920s and the 1950s, instructions from the Party’s Central Committee about its form as well as about its content. The very creation of Krokodil, established by a governmental decree, was directly aimed at “attack[ing] the enemies, internal, and external, of the Soviet Union” (185). In that respect, as the author astutely remarks, Soviet state-sponsored satire appears as a paradoxical object, since satire, as a counter-power and as means of opposition, usually targets an established power. If Soviet satirical literature has been widely studied, the visual manifestations of Soviet laughter still need to be investigated, hence Gérin’s choice to exclusively deal with visual objects, through an interdisciplinary lens encompassing graphic satire in posters, journals, circus, theatre, and cinema, each medium being supplied with a useful and synthetic overview of its uses from eighteenth-century Russia to Soviet times. Such a cross-media approach is more than welcome given the widespread circulation of images and ideas among various media in that period and given the fact that Soviet artists would very often work simultaneously in different fields of creation. Relying upon numerous archives and official materials and focusing upon the “production” of a Soviet laughter, “Gérin unveils, as an heir of the formalists, its various strategies (caricature, collage, irony, parody) and its reappropriation of pre-revolutionary popular devices, tools, and formats. She illustrates these points by scrutinizing three dominant topics handled by Soviet visual satire: the campaign against everyday life (byt), the anti-religion campaign, and the campaign against Trotsky. As the author explains, what launched her research was her encounter in 1988 with the British collector David King, a writer, photographer, and graphic designer, who established one of the richest and largest world collections of Soviet visual culture. The David King Collection, acquired in 2016 by the Tate Library and Archive, was highlighted, for instance, in the 2017 show presented at the Tate Gallery in London, Red Star Over Russia: A Revolution in Visual Culture 1905-1955. Gérin’s close knowledge of King’s collection enables her to include rare and fascinating images in her analysis. For instance, when she discusses the practice of auto-criticism in Soviet satirical journals in the 1920s and 1930s, she brings up covers and illustrations which display a reflexive meta-discourse not only about the journals’ satirical activity as such but also about the very material issues they are facing, such as bureaucratic obstacles. Framing her study with a conceptual and historical overview of the various understandings of humour and laughter and of their mechanisms from antiquity to the present, including such thinkers as Aristotle, Herbert Spencer, James Sully, Theodor Lipps, and the founders of the GVTH (General Verbal Theory of Humour), Gérin traces Soviet discussions and debates on humour and satire, in their attempt to define a specific Soviet and socialist laughter, distinct from a bourgeois and a Western one. Gérin dedicates significant attention to the figure of the Soviet Commissar of Enlightenment, Anatoly Lunacharsky (1875–1933), who exerted a tremendous influence upon Soviet arts and culture and who, ironically, always expressed his caution towards a mere ideological art deprived of aesthetic qualities, as well as towards a state favoring one artistic trend to the detriment of another. While Lunacharsky’s role and career as a Commissar of Enlightenment has been thoroughly scrutinized by researchers such as Sheila Fitzpatrick, his strong interest in satire, caricature, and humour has remained overlooked. An author himself of several satirical plays, Lunacharsky wrote theoretical and critical texts on humour, including an unfinished book on laughter (preserved in the Russian National Archives of Literature and Art, RGALI), a textual corpus which Annie Gérin is the first to handle in detail and to translate. Her study includes a valuable English translation of Lunacharsky’s 1931 speech “On Laughter,” in which he develops his specific vision, coined from a Marxist perspective, of laughter as a phenomenon with a social function, which has to be “organized” as a tool of class struggle. A powerful and poisonous revolutionary weapon able to reveal the insignificance of the enemy and therefore to weaken him, laughter represents an element of a tremendous importance in the “struggle for the emancipation of human beings” (206). Lunacharsky’s speech is inscribed within the acrimonious debates, mapped by Gérin, occurring in the end of the 1920s, about the relevance and usefulness of Soviet satire in the context of the “successful construction of ‘socialism in one country’” (177). A passionate collector and connoisseur of satiric graphic material, Lunacharsky clearly defends the necessity of a Soviet laughter, even establishing in 1930 a Commission for the Study of Satirical Genres at the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Its purpose was to gather a massive archive and library on worldwide visual satire, in order to analyze and encompass various satirical practices through time and space. As Gérin demonstrates, Soviet uses of laughter go through a shift in the 1930s as the paradigm of socialist realism shapes the Soviet cultural landscape. Satirical practices become less experimental, more controlled, and more risky in times of increased state repression and Stalinist Terror. With the establishment of the First Five-Year plan, the artists are expected to celebrate Soviet achievements in a light and palliative manner—hence, in theatre and cinema, a sharp turn from enlightening satire to comedy, a happy and entertaining laughter, as advocated by Boris Shumyatsky, the head of Soyouzkino. Lunacharsky’s positions increasingly become marginalized, including his defence of satire, which he tries to reconcile with the goals of socialist realism, describing the exaggeration and stylization encapsulated in caricature and in satire as methods to reveal reality (184). Carefully documented, Gérin’s book provides a very precious contribution on Soviet visual humour, akin to seminal studies on the topic such as the 2002 two-volume edition of Agitmassovoe Iskusstvo Sovetskoi Rossii: Materialy i dokumenty [Mass-Agitational Art in Soviet Russia: Materials and Documents].[2] Some remaining questions might be handled in future works: how to study Soviet visual satire from the perspective of the dynamics between centres and peripheries? What about censored satirical material, especially when representing main Soviet figures? In the discussion on cinema and theatre, it would have been stimulating to discuss lesser-known cases, which challenge traditional narratives, such as A Severe Young Man by Abram Room (1936), a film subject to censorship and displaying an unexpected satirical message against official credos, endowed with a baffling use of nonsense for that time. In some cases, Gérin’s cross-media approach could go further. When examining the campaign against religion in satirical journals, and especially their challenge to represent visually the absence of God, Gérin could have brought up the case of films such as October by Sergei Eisenstein (1927) or Enthusiasm by Dziga Vertov (1931), in which the filmmakers experiment with filmic devices in order to foster conceptual and satirical atheist discourses, with very similar concerns and strategies to those of the illustrators Gérin comments upon. Annie Gérin’s book will be, therefore, of great interest for historians of the Soviet Union as well as for researchers in visual studies, and especially for scholars working on caricature and satire. It maps exciting new paths of research, which will be, hopefully, explored. An art historian and a specialist of Sergei Eisenstein's oeuvre, Ada Ackerman works as a Permanent Researcher at THALIM/CNRS (French National Research Center). — [email protected] [1] Robert Bird, Christina Kiaer, Zachary Cahill, eds., Revolution Everyday: A Calendar. 1917–2017, exh. cat. (Milan: Mousse Publishing, 2018); Natalia Murray, ed., Revolution. Russian Art: 1917–1932, exh. cat. (London, Royal Academy of Arts, 2017); Nicolas Liucci-Goutnikov, ed., Rouge. Art et utopie au pays des Soviets, exh. cat. (Paris: RMN, 2019). [2] Irina Bibikova, ed., Agitmassovoe Iskousstvo Sovietskoi Rossii: Materialy i dokoumenty. 1918-1932, 2 vol. (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 2002). Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|