|

Claudette Lauzon

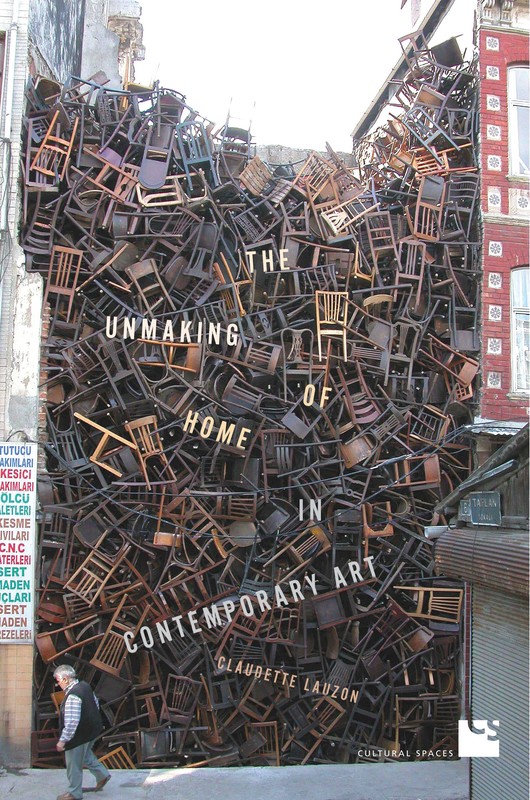

The Unmaking of Home in Contemporary Art Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017 212 pp, 50 b/w illus. $65 (hardback) ISBN: 9781442649828. At the end of the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy wakes up in her own bed – in the midst of the dust-bowl of Kansas – and exclaims, “There’s no place like home.” After her colourful experience in the Land of Oz, the film’s narrative reinforces the superiority of home and its security and sense of belonging – no matter how bleak the reality may be. The film, through the lens of fantasy and escape, asks, what makes a home? How do we measure the idea of home? The Wizard of Oz offers a rich set of dramatic narratives and ambiguous metaphors of home, homelessness, and homeliness that have also underpinned and informed the work of theorists as well as many artists. Judith Butler and Mieke Bal are the theorists to whom Claudette Lauzon turns most frequently in her book The Unmaking of Home in Contemporary Art. For Judith Butler the home is a starting point for the performativity of identity and, because of the regulatory nature of home, it is often represented as an oppressive structure that needs to be contested in order to honour diversity and dignity. Mieke Bal regards the home as a place of the (overly) familiar and therefore there is a need to escape it. As Lauzon traces the aesthetics of migration, or at the least the ways the in/visibility of migratory culture is traced temporally on the body, Bal is very much behind her arguments. From the outset, The Unmaking of Home in Contemporary Art situates home as an uncomfortable space by informing the reader that, “In a world where the notion of home is more traumatizing than it is comforting, artists are using this literal and figurative space to reframe human responses to trauma.” This book sets out to perform itself as a site of disconnection from home. Lauzon has sought out artists who situate home as destabilized and a place of melancholy. The three central themes of the book are: melancholy as a source of political agency (with social justice as a sub-theme), witnessing (as) dispossession, and the unhomely. I find this to be a narrow stance, even though much of the art that Lauzon uses to animate her arguments is provocative, political and often powerfully inventive. She brings to our attention artists working in many different contexts and political situations in or through which they significantly examine itinerancy and attachment to place. The artists highlighted in the book include Mona Hatoum, Doris Salcedo, and Emily Jacir, amongst many others whose art practices activate and draw attention to spaces of belonging and un-belonging. For Lauzon, “these artists exemplify…the unhomely aesthetic that prevails in contemporary art practice and contemplates the global politics of borders, belonging, and the unhomely nature of contemporary global society” (176). As described by Lauzon, Mona Hatoum’s work explores themes of home and displacement, using common domestic objects that often, on closer inspection, reveal menacing qualities. Interior Landscape (2008) and Mobile Home (2005) consist of everyday objects: a steel bed frame in the first and, in the second, a variety of nondescript pieces of furniture and household items framed above and below by a pulley system which carries objects across the space with wire and clothespins. Hatoum’s work evokes home but it a place that is neither comforting nor long-lasting. Doris Salcedo’s installations also rely on commonplace items such as chairs and clothing, often with wood, wire and concrete incorporated. Her objective is to give form to pain, loss and trauma as based on her life experiences in Columbia, where members of her family were amongst the many kidnapped during political strife. Emily Jacir’s work refers to the depopulation of Palestine. The embroidery on the rough and utilitarian refugee tent plays with both the knowledge and recognition of cities that have been destroyed and the on-going need for tents as a result of the regular demolition of Palestinian towns and homes by Israeli tanks and bulldozers. For each of these artists, home is a fragile or vulnerable place often related to movement and migration often through upheaval or violence. Because of my research and curatorial work with Indigenous artists (contemporary and historical) I’m inclined to suggest that if Lauzon had examined and included contemporary North American Indigenous art practice, she would have found artists who are expressing or situating home as land, often doing so in a much less anxious manner. The notion of land and territory has been destabilized by colonialism and trauma since the point of contact, but there is also strength in the work that does not (in my opinion) dwell on vulnerability, disconnection, or melancholy. The perspective offered by Indigenous experience of the land and the importance of place is integral to the art practice of many artists, and offers a way to reframe and broaden conceptions of home. I am thinking about artists such as Shelley Niro (Kanien'kehá:ka), Cheryl L’Hirondelle (Métis/Cree), Dylan Miner (Wiisaakodewinini - Métis), Hannah Claus (Kanien'kehá:ka and English) and Dana Claxton (Hunkpapa Lakota). Cultural belonging, place-making as intentional practice, political activism, the semiotics of place: concern for society as a whole is often evident in work by these artists and their contemporaries. It can also be about fragility and perhaps nostalgia but I would hesitate to characterize the work as driven by melancholy or instability. There is much in the book to commend it – Lauzon knows her subject well and she has usefully introduced artists that myself and others may be less familiar with, such as Petrit Halilaj, a Kosavar artist who incorporates or re-creates artefacts from his past. For this artist his personal experiences of home are deeply intertwined with geopolitical events and dislocation; or British artist Donald Rodney whose photographic image, In the House of My Father (1996-97) is a close-up of the artist’s hand, in which is placed a tiny sculpture of a house. The sculpture, constructed from pieces of Rodney’s own skin exists as an independent work. In his short-lived career the artist brought together the notion of home and identity through his familial experiences of emigration (Jamaica to United Kingdom), illness (sickle cell anemia), and life expectancy, with the home as a symbol of fragility. The book shows how artists explore, in a variety of media, the manner in which house and the idea of home and our relationship to these is embroiled in complex overlappings of gender, race, class, and status, and the work of these artists adds to our understanding of the tenuous nature of home as, through lived experiences, they examine home as a shifting notion. This book and its subject matter are timely as we are grappling with global issues of homelessness, immigration, migration, massive waves of refugees, and the separation of families crossing borders to escape violence, terror, or economic uncertainty only to be confronted with a new set of governmental prosecutions. The notion of there being “no place like home” can be considered saccharine if not annoyingly dated and we require a text like this that seeks to question how memory, longing, and displacement impact our understanding of or sense of belonging to a particular home in difficult situations. We can respect the artists who work to unsettle our complacencies, yet I think we can also hold onto ideas of home, land, territory, and community, which are reinforced with shared experiences and belonging. Memories of the past can foreshadow future resilience. Lori Beavis, PhD. is a curator, art educator and art historian based in Montreal. Identifying as being of Mississauga Anishinaabe & Irish-Welsh descent, she is a band member of Hiawatha First Nation at Rice Lake, Ontario. Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|