|

Caroline A. Jones

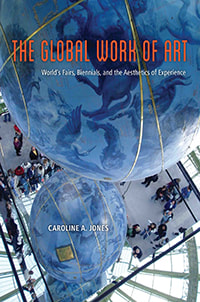

The Global Work of Art: World’s Fairs, Biennials, and the Aesthetic of Experience Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017 400 pp., 37 colour plates, 128 b/w illus. $65 (cloth) ISBN: 9780226291741 The focus of Caroline A. Jones’ new book, The Global Work of Art: World’s Fairs, Biennials, and the Aesthetic of Experience, is the widening of the international and global art world. She bases her study on the lineage of world’s fairs and biennials and examines globalisation in contemporary art. Building outward from an exhibitionary complex that began in the nineteenth century, Jones probes key concepts like cosmopolitanism, nationalism, internationalism, transnationalism, globalism, and aesthetic experience. Jones argues that the contemporary biennial circuit holds the potential for global art to make viewers aware of global entanglements through an aesthetic “experience.” She emphasizes the action and agency of artworks as they move transnationally through and between world’s fairs and now biennials. For Jones, “Art works. It is and has been active, working on the viewer historically, working on me still” (x). Conceptually, this entails thinking about “work as a verb” (x) in order to reflect the historical transition of art from an object to an experience. What results for visitors of these events is an awareness of art’s global position, or “globalism.” Jones describes this as “an aesthetic response to economic, technological, and cultural processes of globalization” (xiii) that resists the longer history of the art market. In the first of its seven chapters, The Global Work of Art outlines its theoretical framework, which Jones refers to as “blind epistemology.” In her view, world’s fairs were conceived as microcosms of the world or the world-as-picture. In their emphasis on sight and perspective, they materialized Enlightenment philosophies. Jones, however, traces the importance of blindness in epistemology from Plato to Descartes to Georgina Kleege in order to rethink how biennial culture produces a different sort of knowledge through world-picturing. Where Martin Heidegger conceived of the world-as-picture as a frame for a singular idea, Jones argues that it is partial and globally linked. From nineteenth-century world’s fairs to twentieth-century biennials, artists have critiqued the world-as-picture model through the development of strategies of blindness that treat multisensory knowledge as an aesthetic experience. In her second chapter, Jones convincingly argues that blind epistemology enters biennial culture by shaping and contemplating the finite limits of situated knowledge. Artistic techniques of conceptualism and institutional critique, which were part of the turn towards an aesthetics of experience, offer multisensory strategies of knowing that challenge the notion developed at world’s fairs of the world-as-picture. She develops a lineage from Hiram Powers’ work The Greek Slave (first completed as a plaster model around 1843), which was an international sensation prior to its display in London’s Great Exhibition, to twentieth-century artists like Pablo Picasso and Max Bill. She then moves on to global postwar artists, such as Hélio Oiticia and Javier Téllez, and ends with contemporary artists, such as Cai Guo-Qiang and Tino Sehgal. The case of Power’s marble statue is most telling, especially as it relates to Jones’s arguments regarding the physical encounters with art that fairs produced, and how their context often speaks to difference, that is, the difference between local and global situations. For Jones, biennials inherited and built upon the international art audience of world’s fairs by replicating earlier notions of the world-as-picture. Like world’s fairs, biennials operate within a European colonising legacy. However, biennials have had a more global goal, one that embraces experience as the driving force behind aesthetic changes in contemporary art. These changes to the content and form of contemporary art were produced, in part, by the way biennials incorporated a recurring structure into their organization. The repetition of biennials retains and builds audiences, thus producing a “biennial culture” that is, as Jones argues, conditioned by the “practice and appetites” of artists and curators who provide visitors with an “art of experience” (86). In her third chapter, Jones historicizes the development of biennial culture from the Venice Biennale to the present day. Jones explains that biennials both implicate the nation and attempt to promote a kind of universalism that reinforces difference. However, as outlined in her fourth chapter, the early editions of the São Paulo Biennial briefly refused global difference. Jones’ southern hemispheric focus on the São Paulo Biennial aligns with recent scholarship that emphasizes historical reconstruction from a postcolonial and southern perspective, including Charles Green and Anthony Gardner’s Biennials, Triennials and Documenta: The Exhibitions that Created Contemporary Art (2016). Scholars like Rafal Niemojewski, who posits an alternative genesis of contemporary biennials from the Havana Biennial, would contest her teleological insistence on the development from world’s fairs to biennials. For Niemojewski, the postcolonial agenda that informed the Havana Biennial distinguishes its new discursive programs and socially aware art. Jones’ important contribution to the study of the early São Paulo Biennial lies in her discussion of how artists used “geometric nonobjective art” to emphasize their Brazilian roots and, in turn, “to eradicate signs of difference” (114). This eradication was unlike the work of artists at the margins at earlier world’s fairs and the Venice Biennale, who felt the necessity to use an “international” language of art devoid of local meaning to engage in an artistic dialogue. While some scholars, like Rasheed Araeen and Gerardo Mosquera, have argued that artists from the margins are still required to do this, Jones demonstrates through archival research that there has been a turn from modern internationalism to event-driven experience. The early São Paulo Biennials, she argues, reintroduced the friction between the local and global. Also important was the work of artists such as Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, whose transnational discourse was also influential to conceptual art emerging abroad. In her fifth chapter, Jones conceptualises what she calls “tactics of the trans.” This refers to the transactional agency pursued by Clark, Oiticica, and other Brazilian artists at the São Paulo Biennial, which required new terms for naming new states of being. In tracing these shifting terrains, Jones prefers “trans” to “internationalism,” “the world picture,” or the global, because of its adaptability as a prefix that can be added to words such as cultural, national, action, form, and so on. It calls for the study of globalities as crossing paths. By mobilising specific aesthetic and discursive processes, Brazilian artists blurred national borders and simultaneously situated visitors locally and globally through a presumed artistic awareness in of art centres, such as London and New York. Artistic agency, Jones states, “impel[s] visitors to engage in deep reflection on the apparatuses of biennial culture and the worlds connected by them” (193). The emphasis and main contribution of The Global Work of Art takes shape in the last two chapters of the book. The immersive experiences that biennials offer oppose the former universalizing world-as-picture schema presented at world’s fairs. Like Nicholas Bourriaud’s concept of relational aesthetics, which takes audience participation and social context as elements of artistic practice, Jones proposes the concept of “aesthetics of experience” for its critical potential. Because experience comprises time, place, history, and the body, it is the site that situates local difference, and, at the same time, critically negotiates and reconfigures global concepts. In his assessment that biennials and contemporary culture in Latin America are an expedient means for political and corporate interests, scholar George Yúdice has likewise suggested that art “works.” But as Jones argues, “Art’s workings should always leave us with work to do” (223). This is where critical globalism demands viewers to question “what conditions … their view” (229). There is no guarantee that visitors will willingly take on this responsibility, especially if the work is too conceptual. Jones cites as examples of works that allow visitors to take on this responsibility Martin Kippenberger’s contribution to the 2003 Venice Biennale, which was installed posthumously in the German pavilion, and Santiago Sierra’s intervention at the Spanish pavilion. Artists like Kippenberger and Sierra, are, according to Jones, doing their part in biennial culture to enlarge the “focus on where we are in an entangled world, to make us aware, through experience, not of our distanced relation to a picture but of our enmeshment in situations” (249). There are numerous publications on biennials that are either introductory and anthological (Bydler, Altshuler, and Filipovic) or limited to a specific exhibition (Vanderlinden, Weiss, and Lagnado). By focusing on a genealogical history of biennials in art history, The Global Work of Art joins Lawrence Alloway’s 1989 publication on the Venice Biennial and the recent publication by Charles Green and Anthony Gardner (2016). Offering a challenging and dense text on the global workings of art, it optimistically foregrounds critical work done by the public. The next task for scholars is, perhaps, to reveal globally enmeshed existences that Jones sees as “no longer masterable as picture” (249). Amy Bruce is a PhD candidate in Cultural Mediations at the Institute for Comparative Studies in Literature, Art, and Culture at Carleton University [email protected] Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|