|

Josephine Jungić

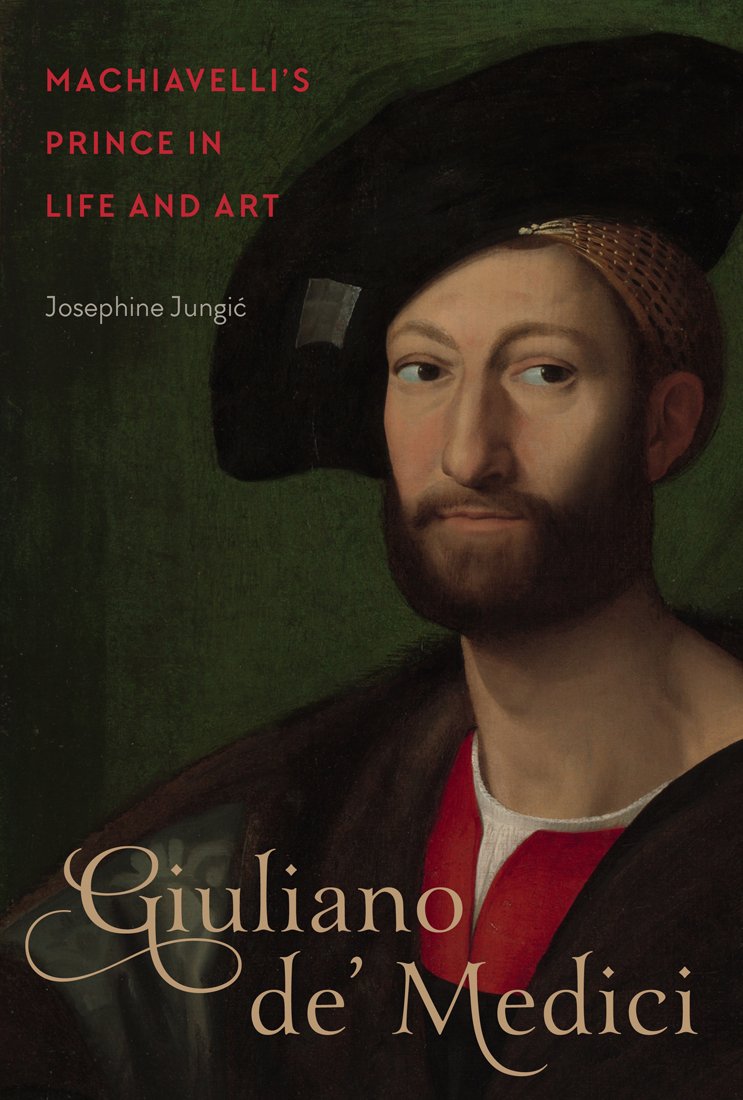

Giuliano de’ Medici: Machiavelli’s Prince in Life and Art Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2018 312 pp. 40 colour illus. $49.95 (hardcover) ISBN 9780773553200 Loved and feared as one of the most powerful families in Renaissance Italy, the Medici were politically astute, well-connected, fabulously wealthy, and patrons of the most famous artists of their time, including Michelangelo and Raphael. Their patronage of the arts has received intense scrutiny by distinguished art historians, including Charles de Tolnay, Johannes Wilde, John Pope-Hennessey, John Shearman, William Wallace, and Gabrielle Langdon, to name just a few, and we feel we know their story well enough not to expect any dramatic new perspectives. Yet, in this fascinating study, Josephine Jungić shows us there is still much to discover. The book focuses on the much-maligned figure of Giuliano de’ Medici (1479–1516), whom most art historians meet through the study of Michelangelo’s celebrated funeral chapel in the family church of San Lorenzo in Florence, known as the New Sacristy. Taking her point of departure from the enigmatic text that Michelangelo scribbled on a drawing of architectural mouldings for the tomb, Jungić entangles the reader in an engrossing tale of politics, patronage, and artworks that succeeds in revising the well-accepted perception of Giuliano as an ineffectual, dissolute, pleasure-seeking lightweight with little political acumen. Offering the first modern, full-length scholarly biography in English of this marginalized figure,[1] the book provides a densely-woven narrative which the author calls a political biography. Yet, for art historians, what emerges from this forensic study of correspondence, poems, treatises, artworks, and other sources, is the ability to see Giuliano’s patronage through fresh eyes, without the negative bias that has accumulated around him over the centuries and which continues to be perpetuated by modern historians. Jungić shows that, despite dying at age thirty-seven in 1516, Giuliano—the youngest child of Lorenzo the Magnificent and Clarice Orsini—was politically and culturally influential during a turbulent period in Florentine and Italian history. This was an era of outstanding achievements in art and literature and of intense political conflict, as France, Spain, the Holy Roman Emperor, and the pope jockeyed for position. The book begins by asking why this particular Medici has consistently “been portrayed as irrelevant at best and as a degenerate at worst” (6). Investigating his connections to artists, intellectuals, religious reformers, and political figures, and building on Dale Kent’s study of patronage networks and the importance of friendships, Jungić aims to prove how much Giuliano was loved, valued, and admired by such cultural giants as Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, Machiavelli, Pietro Bembo, Baldassare Castiglione, and Cesare Borgia. Starting with the enigmatic verses by Michelangelo written in 1524, the author singles out the last line, which has long puzzled art historians eager to dismiss or downplay Giuliano’s cultural and political influence, including such notable scholars as Charles de Tolnay, Creighton Gilbert, and Howard Hibbard. The first part of the text, a dialogue between Night and Day, speaks to how Giuliano’s early death has extinguished the light of the world: “he, dead, has taken the light from us, and with his closed eyes has locked ours shut, which no longer shine on earth” (3). However, the final line asks “What then would he have done with us while alive?” Dispelling the suspicion raised by some scholars that the representations of Giuliano and Lorenzo as Day and Night respectively have been attributed incorrectly (starting with Herman Grimm in the mid-nineteenth century and later with Martin Weinberger, Howard Hibbard, and Richard Trexler, all of whom suggest that the characteristics of Day, associated with the tomb of Giuliano and typically understood as representing the active life, are more suitable to Lorenzo), Jungić argues that Michelangelo’s text has been misinterpreted or ignored because scholars could not believe that Giuliano could inspire words that imply the world has been robbed of a figure of such future cultural and political impact, one who would have tempered the Medici’s monarchical ambitions. Jungić persuasively ascribes the biased interpretation of Giuliano to political differences: he was at odds with his family in his wish for the restoration of a republican government in contrast to the desire by the rest of the family to see their power restored. Thus, political differences during a period of religious reform account for his poor treatment in the historical record, from in his own era on and into modern times. While proceeding chronologically to treat the major moments in Giuliano’s career, starting with the Medici family’s return to Florence in 1512 after eighteen years of exile, the chapters develop in detail Giuliano’s friendships with artists, writers, and political figures. Chapter Seven, on Giuliano’s relationship with Leonardo, is particularly compelling, for it allows Jungić to highlight the artist’s less-discussed expertise as a military architect and engineer, including his work on military technology for the Sforza court in Milan and for Cesare Borgia. Giuliano had been forced to relocate to Rome and relinquish his role in governing Florence by his brother, the newly elected pope Leo X, after a plot to assassinate him was uncovered. Once settled in the heart of the old city, Giuliano invited Leonardo to join him. Rome at this time was a leading art centre, with Michelangelo and Raphael involved in major papal commissions along with numerous artists who were attracted to the city hoping for similar commissions. Although Leonardo spent almost three years on and off in Rome before heading to France after Giuliano’s death to join the court of King Francis I, his years in Rome have not received much attention. Jungić attributes this to a “long-standing bias against Leonardo’s Roman period” (137), beginning with Vasari’s dismissal of this phase since it did not produce much painting. Jungić argues that Leonardo was invited because of his talent as a military architect and engineer, and he worked on several engineering projects for Giuliano. The projects were related to Leo X’s plan to form a state from the cities of Parma, Piacenza, Modena, and Reggio to be governed by Giuliano. One of the projects was to drain the Pontine Marshes. This work was suspended on the death of Giuliano and abandoned on the death of Leo X in 1521. Another project was to build a large parabolic burning mirror that could be used for both industrial and military purposes. This project also ended upon Giuliano’s death. Giuiliano’s patronage of Leonardo is significant for Jungic’s argument, since not only does it demonstrate his influence as patron of one of the most important artists of his time, but also that he was thinking strategically as a soon-to-be prince eager to protect his own territory. An even more important contribution of the book is the exploration of Giuliano’s friendship with Machiavelli, which is developed over several chapters. Through a close reading of Machiavelli’s poems, letters, political writings, and other documents, Jungić convincingly establishes that, contrary to scholarly opinion that Giuliano had little direct contact with the author of The Prince, there was in fact a “close relationship” with Machiavelli that lasted from 1502 to Giuliano’s death in 1516. Making the case that Machiavelli composed two poems for Giuliano in Imola in 1502, wrote the “Letter to a Noblewoman” to Isabella D’Este on Giuliano’s request, composed Ai Palleschi “as a warning to Giuliano,” and sent him two sonnets while in prison, Jungić argues that in the last months of 1513 Machiavelli conceived The Prince “for the benefit of Giuliano.” As Giuliano’s friend, Machiavelli was “deeply concerned for his future as prince” in light of Leo X’s proposed new state (162). Addressing the key questions of intention and audience, Jungić contends that “Machiavelli’s reason for writing The Prince was to give Giuliano helpful advice on how to acquire and maintain his new state” (161). Although Jungić notes that there is “no direct evidence that Giuliano ever received or read the book” (171), she argues that it “would have been extraordinary if he did not read it” (172). While many scholars argue that Chapter Twenty-six was composed later, with most assuming it was written not for Giuliano but for Giuliano’s nephew Lorenzo, Jungić claims that if one approaches the text “free of bias against Giuliano,” then the idea that Chapter Twenty-six was part of the original work and was intended for him makes sense. Advancing this argument allows Jungić to position Giuliano as “Italy’s redeemer” (173). Jungić’s interpretation of the friendship between Machiavelli and Giuliano, and her argument that The Prince was written as “a small book of advice for his new state” (159), offer the opportunity to provide a new reading of the 1515 portrait of Giuliano in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (fig. 38). Proposing that the work is an original by Raphael (which contradicts current scholarly consensus that it is a copy), Jungić reads the work as an official state portrait, intended for his new role as head of the new principality proposed by Leo X. Pointing to the significance of the representation of Castel Sant’Angelo through the window behind Giuliano, and to the paper held in his right hand, Jungić interprets the image as presenting Giuliano as Machiavelli’s new prince, for the central theme of The Prince is that good government depends on the use of “good laws [the paper] and good arms [the Castel]” (193). As Jungić speculates: “Could this neglected portrait have historical significance far beyond what was previously thought? Could it, in fact, suggest that Giuliano had not only read The Prince but was also willing to follow Machiavelli’s precepts with respect to maintaining strength in arms and dispensing justice through good laws?” (194). Although one might take issue with aspects of Jungić’s revisionist biography of Giuliano and some of the necessarily speculative claims and hypotheses, the text is persuasive, and demonstrates the value of continually questioning received wisdom by going back to the sources. The impeccable scholarship, crisp writing, and the unrelenting drive to address historical biases make this a compelling study. The press has produced a handsome volume, with a beautiful dust jacket graced by the portrait of Giuliano (here attributed to Raphael), a frontispiece with a detail of Michelangelo’s sculpture of Giuliano from his tomb in the New Sacristy, and forty colour illustrations. The author has included portraits of many of the historical figures discussed in the text, which helps to bring the past to life. After reading Jungić’s text, we can return to Michelangelo’s figure of Giuliano in the Medici Chapel with new respect, understanding, and even sympathy for this hitherto misrepresented Medici. Erin J. Campbell is a Professor in the Department of Art History & Visual Studies at the University of Victoria. —[email protected] [1] The only recent biography of Giuliano appears to be a brief entry by Stefano Tabacchi, “Giuliano de Medici,” in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 73 (Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 2009), 84–88. Before Tabacchi, for a detailed biography one would have to go back to the 1939 study of Giuliano’s poetry by Giuseppe Fatini, “Di Giuliano de’ Medici Duca di Nemours e delle Sue Poesie (1479–1516): Cenni Biografici,” in Giuliano de’ Medici, Poesie, a cura e con uno studio di Giuseppe Fatini (Florence: F. Le Monnier, 1939), vii–xcvi. Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|