|

Jocelyn Jean, Gilles Lapointe, and Ginette Michaud, eds.

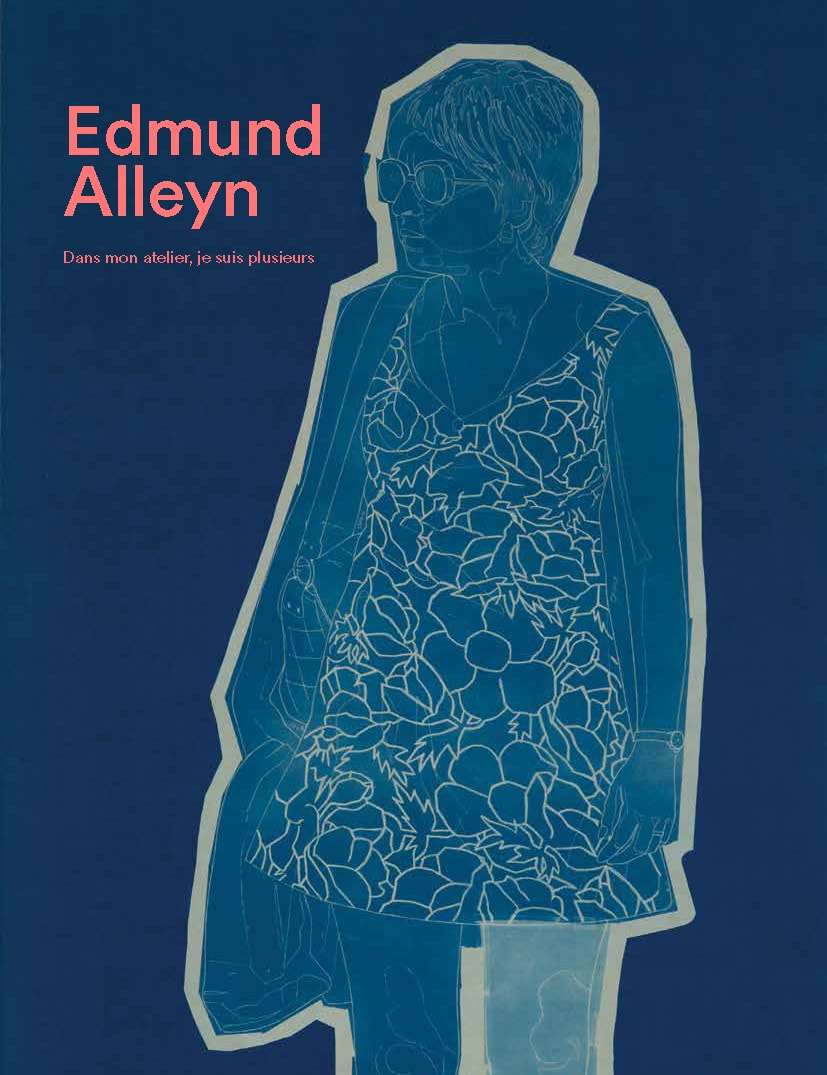

Edmund Alleyn, Indigo sur tous les tons Montréal: Les éditions du passage, 2005 280 pp., 100 + colour and b/w illus. Out of print (paper) ISBN 2-922892-14-X Edmund Alleyn De jour, de nuit: Écrits sur l'art Jennifer Alleyn and Gilles Lapointe, eds. Montréal: Les éditions du passage, 2013 102 pp., 49 b/w and colour illus. $19.95 (paper) ISBN 978-2-922892-65-9 Mark Lanctôt, ed. Edmund Alleyn: Dans mon atelier, je suis plusieurs Montréal: Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal, 2016 216 pp., 100 + b/w and colour illus. $39.95 (paper) ISBN 978-2-551-25749-2 Gilles Lapointe Edmund Alleyn: Biographie Montréal: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2017 448 p., 100 + b/w and colour illus. $59.95 (paper) ISBN 978-2-7606-3712-2 Au début, il ne s’agissait que d'être peintre, plus tard, il importait d'être aussi un artiste. Et en devenant artiste, il devenait de plus en plus difficile d'être peintre. —Edmund Alleyn, “Fragments posthumes,” in De jour, de nuit Although I was invited to write about the last three titles on this list, I can't really do so without mentioning the first, a celebration of Edmund Alleyn that includes texts and artworks of various kinds by more than fifty writers, artists, friends, and family members, collected just months before the artist’s death, with his participation. The book also had two inserts: one was a DVD including a film made by Charles Chaboud at the time of the 1970 showing in Paris of Alleyn's Introscaphe (discussed below) and also a 2001 film by Jennifer Alleyn, in which she interviews her father in his Montreal studio; the other was a small, fifty-page “carnet” of Alleyn’s notes and poems edited by Gilles Lapointe and Ginette Michaud. I can remember being struck, at the time, by the bold and beautiful design of Edmund Alleyn, Indigo sur tous les tons. The book is now out of print, but anyone who really wants to appreciate the other three publications would be well advised to consult a copy, if possible. My interest in these books was piqued by the involvement of Ginette Michaud and Gilles Lapointe, whom I have known as friends and collaborators over many years. Michaud is a celebrated editor and writer on Quebecois and French authors, notably Jacques Ferron, Jacques Derrida, and Hélène Cixous. Lapointe is recognized especially as a prolific scholar on Borduas and the Automatist movement. Edmund Alleyn was an infamous thorn in the side of us Automatistophiles, ever since he participated in a mocking submission of “false” abstract paintings, chosen for exhibition by Borduas at the last major show sponsored by the Automatist group, La matière chante (1954). I have learned that Alleyn and Lapointe met, at Alleyn’s request, after the latter read Lapointe’s book L’Envol des signes: Borduas et ses lettres (1996). While Alleyn never understood or appreciated what he regarded as the Borduas cult, Lapointe was ready to defend it heatedly, and Alleyn liked an argument. Thus began a friendship that led to interviews, to the collecting and editing of some of Alleyn's writings, and eventually to this series of remarkable publications. De jour, de nuit: Écrits sur l’art is based on the “carnet” of short texts by Alleyn inserted in Indigo sur tous les tons. It has been augmented with more texts and with original drawings to make a handsome little volume. The catalogue of the 2016 solo exhibition organized by the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (MAC) includes texts by Lapointe and others (described below), and was obviously the starting point for Lapointe's biography, which has to be at the centre of this review, because it provides the information I need to explain not only the genesis of Alleyn's work, but the genesis of this interesting and varied series of books. George Edmund Alleyn was born in Quebec City on June 9, 1931 into a comfortable Irish-Quebecois family. As his first language was English, he did badly when his father obliged him to continue his studies in French, first with the Jesuits in Quebec City and later at Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf in Montreal. In one of the brief poems included in De jour, de nuit, Alleyn wrote, “I am English to the bone/and French to the skin.” His interest in visual art began early, encouraged by an aunt, and he indulged it especially during summer holidays in Kamouraska. By his late teens, he was in full rebellion against his conservative parents, going to New York in 1949 to hang out and do sketches in jazz clubs in Harlem. As his parents wanted him to study medicine, they resisted at first, but eventually allowed him to enter the École des beaux-arts de Québec in 1951, under the friendly tutelage of Jean Paul Lemieux. Gilles Lapointe’s biography provides a full description of the École des beaux-arts at the time—its programs and its professors—most of whom (with the exception of Lemieux) failed to impress Alleyn. Much of this information is based on a half-dozen interviews with Alleyn conducted by Ginette Michaud and Gilles Lapointe in 2004, along with autobiographical material written by Alleyn and an important 1976 Radio-Canada interview with Guy Robert entitled “Un artiste et son milieu.” Alleyn was a hard-working student, reading art history while getting a sense of what was happening in New York. During his time at the École des beaux-arts, he was a figurative painter, aware of, but not swayed by, the theories of Clement Greenberg, which he had read about in Life magazine. Gilles Lapointe describes in some detail the moment when Lemieux and Alleyn made their mocking contributions to La matière chante in April 1954, since it became quite an important public issue, provoking debates between the “figuratives” of Quebec and the “abstractionists” of Montreal. Before long, Alleyn’s serious work attracted the attention of the young, but very influential painter and critic Rodolphe de Repentigny, who, until his untimely death, remained a firm supporter of Alleyn's work. He wrote, for example, about Alleyn's exhibition in February 1955 at the Agnès Lefort gallery, an exhibition that could be seen as marking the real beginning of the young artist’s career. Graduating from the École des beaux-arts, Alleyn was awarded the province’s Grand prix du concours artistique, which would pay his living expenses for two years in Paris. At the same time, his painting was becoming increasingly non-figurative (though never purely abstract). Cultivating a bad-boy image not unlike some of the Painters Eleven who were emerging in Toronto at the same time, he could have gone to New York, but chose Paris. The intended two years would stretch into fifteen. Lapointe’s account of the Paris period gives glimpses into Alleyn’s private life, especially his reluctant dependence on his parents for financial assistance, shown through the correspondence between the struggling artist (anything but a bad boy in his letters home) and his parents. This, and the story of his love for Anne Cherix—a young, adventurous Swiss artist whom he met in Paris in 1962—are among the few, more-or-less intimate details that Lapointe provides. Clearly, the main concern is to give a substantial history of the progress of an artist through details about his exhibitions, extensive quotations showing and comparing reactions by the press, stories of his contacts with other artists, and descriptions of changes in his working conditions and methods over time. What we have is an important source for anyone doing research on Alleyn and his contexts, both Canadian and French, complete with nearly a hundred pages of bibliographical and explanatory notes. Photographs of people, events, objects, and documents are abundant, and there are also five small colour sections devoted to different periods and styles. Alleyn arrived in Paris as a non-figurative painter whose work nonetheless reflected his memories of Kamouraska and the Gaspé. Within two years, he had his first show at the Galerie du Haut Pavé in Paris, somewhat of a triumph, given the fact that Borduas was still waiting for a solo exhibition in France. The Quebec media showed interest in him, and galleries such as Agnes Lefort and Denyse Delrue in Montreal were exhibiting his work to favourable reviews. During his second show at the Haut Pavé in April 1959, he was noticed by Gérald Bassiot-Talabot, a reputable critic who became a friend, supporter, and important connection to a new generation of artists in Paris. Alleyn returned to Quebec City for a year in 1959, but almost upon arrival was talking of going back to France. He had received a Guggenheim scholarship, his work was selling well, and he was the subject of flattering articles in magazines such as Vie des arts. Back in Paris by December 1960, he was becoming dissatisfied with his rather sombre abstractions and rediscovering an interest in line. He was in a group show entitled Peintres canadiens à Paris along with Borduas, Riopelle, Ferron, Le Febure, and Bellefleur. That same exhibition, minus Borduas, was later hung in Zurich, where Alleyn met Anne Cherix, his future wife. By 1962, critics were noticing a change of style as Alleyn moved towards a more free, colourful, calligraphic, even totemic and primitive quality. Lapointe cites Alleyn (126–127) acknowledging the influence of Haida and Tlingit art in works of this period, such as Jacques Cartier arrivant à Québec voit des Indians pour la première fois de sa vie (1963), acquired at the time by the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, and Un brave en gala (1964), with its three-dimensional, sculptural quality and incorporation of found materials. In passages cited by Lapointe (135) from a 1981 interview, Alleyn says, “Je suis parti dans un trip de peinture indienne,” and, “Je ne me suis pas donné la peine d'interroger ça plus profondément parce que c'était un emballement extraordinaire.” The Montreal painter and critic Marcel Saint-Pierre spoke of Alleyn's “iroquoiseries.” But this was a brief moment for Alleyn, and one that now tends to be underplayed in surveys of his work, because he realized, as he explained in that same interview with Hénault, “J'essayais d’exprimer peut-être une civilisation qui n’était pas la mienne” (142). Much more important for Alleyn's future work were his social contacts and exhibitions the previous year with the “figuration narrative” group in Paris, including Bernard Rancillac, Cheval Bertrand, and Jacques Monory, along with the critic Gassiot-Talabot, already mentioned. Alleyn had stopped painting for a moment at the end of his stay in Quebec, deciding that his art was too dispersed, too unconscious, and an “ego-trip,” so he was ready to collaborate with this new group, whose work tended to be figurative, involved with social and historical questions, but anti-Pop. It was a period of hot debate over the direction that the visual arts should take, and Gilles Lapointe gives a very complete and useful overview (150–155) of the counter-currents at the time, including the debates about technology, painterly methods, figuration/non-figuration, narration, historical allusion, and so forth. Deciding that his art needed to relate to the contemporary world, Alleyn began a lengthy investigation, influenced by Marshall McLuhan, of the effects of technology on humanity, and used fluorescent and metallic paints as well as electronic devices for various kinetic effects in what he called his “tableaux de science-fiction.” There was broadening interest in his work, exhibitions in France, Italy, and Canada (including both the French and Canadian pavilions at Expo 67), and an invitation to spend the summer of 1967 in Cuba. He joined a now-famous association in New York called Experiments in Art and Technology, spent time with Philip Glass in New York, met Michael Snow in the summer of 1967, and took part in a huge exhibition in Berne entitled Science-Fiction. But these new directions were not always well received by the critics or the public, and the works did not sell well. Alleyn was getting impatient with galleries and the whole business of art, while also beginning to think about his next great project: the Introscaphe. Gilles Lapointe devotes an entire chapter to “L’aventure de l’Introscaphe 1968–1970.” These were highly political times in which Alleyn and his engaged artist friends made posters for student demonstrators and marched with them, although he was finally disappointed by a lack of cohesion among students, workers, and artists. He had stopped painting altogether. Lapointe cites an interview in which Alleyn declares, “C’était l’époque où nous lisions McLuhan, Marcuse…. Il me semblait que la peinture n'offrait pas assez de prise. De là, le recours à des séquences d’images comme au cinéma, au son, à toutes sortes de dispositifs cinétiques” (197). Alleyn wanted to reach a wider audience and was not happy that his early technological works were still hung on walls, still seen from the exterior. The Introscaphe would change that. The “gadget,” as he called it, was a highly complex egg-shaped device the size of a small car, with a wooden frame and a smooth, white acrylic exterior. It opened when coins were inserted in a slot, admitting one person who, seated in a rather plush chair that occasionally vibrated in a climate-controlled environment that was alternately hot and cold, was subjected to four and a half minutes of a sometimes-violent and disturbing film by Alleyn entitled Alias, based largely on footage from newsreels and advertising. Lapointe describes how fellow artists and technicians made the object, at great expense of energy and money, over twenty-two months. The idea was not only to provide a more direct communication with the public, but also to do so outside the inhibiting space of museums and galleries, in more public places, and to subvert the art business through direct payment in coin for the experience. In fact, the Introscaphe was shown at the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris in the Fall of 1970 (to considerable success, both popular and critical), but never again in working order—which does not change the fact that it has achieved iconic status in Canadian art. Meanwhile, shortly before this, Jennifer Alleyn was born and the family moved back to Montreal. Attempts to show the device in Canada were foiled by technical problems and eventually it was stored in the artist’s studio. Discouraged by the whole adventure, Alleyn decided to return to painting, but not in the old way: “J’avais envie de peindre, mais je ne voulais pas faire une peinture de style” (232). Lapointe describes him finding his way by photographing unremarkable individuals in public places, then transforming their images into full-length portraits painted on plexiglass, to be placed standing in various poses sometimes looking at, but often indifferent to, the kitschy paintings of sunsets that Alleyn attached to the wall. They are thus both outside of, and part of, the tableau, and they participate in multiple layers of affectionate irony involving not only Quebecois “types,” but also the clichés of popular art. It was a difficult time. Alleyn's marriage with Anne Cherix had ended, and he was broke and forced to do something he had resisted for years: teach. Hired by the University of Ottawa in 1972, he was surprised and pleased to find a stimulating environment. In 1974, there were major showings of his plexiglass figures and tableaux, entitled Une belle fin de journée, at both the Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal and the Musée des beaux-arts du Québec. Lapointe gives a full account of media reactions and of Alleyn’s comments on his painted figures as “nés de ma fascination, depuis des années, avec l’être anonyme,” and his insistence that “pour moi, c’est pas du réalisme” (245). He continued to be an enigmatic figure, and even though his works were showing in Quebec and Ontario in the mid-1970s, he was impatient that his teaching duties did not leave enough time to paint. Lapointe describes Alleyn’s project for a Musée de la Consommation in 1977, and his installation for the Musée de l'hiver at the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal in 1979, along with some projects for public buildings in places like Sept-Isles, as he charts Alleyn’s transformation into a public artist who mixed painting with photography and materials like plexiglass. The following years were difficult for him, but he was becoming fascinated with what he called “l’image-mémoire,” and the result would be a series appearing in the 1990s, whose title was a colour—indigo—and whose images would be highly nostalgic, like the all-indigo, empty power boat floating dreamlike on glassy indigo water in L’invitation au voyage. Near the end of 1990, Alleyn was invited to show the Indigo series in New York, and the public reaction to these works was generally very favourable. In this chapter, Lapointe quotes at length from commentaries on Alleyn, and from interviews with the artist, who often voices his criticism of museums and the art scene in general. Still, he had an important retrospective at the Christiane Chassay Gallery, Edmund Alleyn, Les horizons d'attente 1955–1995, which became the basis for a larger show of the same title at the Musée du Québec in 1997. Alleyn wrote and read a text for that event, and for another at the Ottawa Art Gallery. Lapointe quotes at length from both. In 1999, Alleyn took part in a large group exhibition entitled Déclics, art et société at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, and was pleased to see the Introscaphe (non-functioning) included, along with Chaboud's film and Alias. He was also writing down his thoughts while making preparations for a series that would be called Les Éphémérides, in which meticulously drawn, strangely incongruous objects—presumably surfacing in Alleyn's memory—float against a dark, often grey, blue, or indigo background. Strokes of bright colour are swiped over these static “scenes,” giving the canvases the appearance of two quite different surfaces. One critic called him “un peintre de l'intériorité et de la solitude,” and, during this period, Alleyn, now in his seventies, talked philosophically to his interviewers about important influences (Antonioni, jazz) and failed aspirations. In the summer of 2001, Alleyn learned he had cancer and began to withdraw from contact with anybody but immediate family. In the Spring of 2004, the Musée de Sherbrooke presented Edmund Alleyn. Les Éphémérides. Tableaux et lavis 1998–2004, and he was able to attend the opening. Shortly thereafter, Ginette Michaud proposed the idea of a book on the painter, which would become Edmund Alleyn, Indigo sur tous les tons. The artist died on December 24 of that year. He has been described as a solitary man able to talk of anything except himself (the truth of this can be seen in Jennifer Alleyn's film, Entretien avec toi, published with Indigo sur tous les tons). At the same time, he loved reading, admired and befriended writers, dreamed of writing a novel, tried his hand at poetry, and wrote very articulate, short texts on life and art, some of which are included in the “carnet” of Indigo. Here is a small sample: Travailler comme artiste, c’est tenter de satisfaire une libido bien particulière—tout aussi encombrante que . . . l’autre (17). Je crois que la peinture, aujourd’hui plus que jamais auparavant, est une activité parfaitement paradoxale: elle utilise un maximum de ressources de l'esprit pour un résultat minimalement intelligible (39). La condition humaine en est une de détresse pour une bonne partie des habitants de cette planète, en transit entre deux néants. Mon travail, son contenu, tente de tirer quelque chose de positif de cette détresse; quelque chose de partageable peut-être. Peut-être rien de plus qu'un divertissement pour un bien petit nombre de gens. Une minuscule fente par laquelle le regard peut, de temps en temps, s’échapper (prendre la clé des champs) (58). De jour, de nuit includes such texts and more, along with upwards of forty previously unpublished small drawings and wash drawings, which are strangely mystical and mundane at the same time and relate to the Éphémérides series. Edmund Alleyn: Dans mon atelier, je suis plusieurs, the catalogue of the retrospective exhibition held at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal in 2016, was, no doubt, a huge stimulus for Gilles Lapointe’s biography, as I mentioned earlier. He did, after all, contribute a chronology, a bibliography, and an article discussing Alleyn’s troubled relationship with the avant-garde, using the terms of sociologist Nathalie Heinich to situate him among the figures of “contemporary art” (as opposed to both classical and modern art). Another text by Olivier Asselin and Aude Weber-Houde provides a media-centered, detailed focus on the Introscaphe, which is well illustrated with photos of the “gadget” itself, as well as eight pages of stills from Alias. Vincent Bonin’s essay on Alleyn’s late painting, which he refers to as “les suites québécoises,” makes comparisons with Michelangelo Pistoletto and Michael Snow, and discusses how Alleyn plays with notions of figuration, narration, and space while taking painting outside gallery walls. Bonin also places the painter in a Quebec context that includes groups such as Véhicule Art Inc. and publications such as Parachute. Marc Lanctôt’s contribution makes an association between Alleyn’s paintings and Denys Arcand’s film The Decline of the American Empire, situating them both in the context of postmodernism, which “inevitably redefined not only social relationships, but also aesthetic issues, strongly impacting the power relationships among individuals, the community, and authority” (149). One peculiarity I noticed when considering these books together was that the MAC catalogue shows on its cover a piece from the 1978 series Blue Prints, as well as offering a six-page spread showing others. Yet only Vincent Bonin makes a brief reference to these works, and Lapointe’s biography makes little or no mention of them. This is disappointing to me, because I find them among the most puzzling of Alleyn's works. But, in general, the MAC catalogue is attractive, well-illustrated, and informative, and contains one of those pleasant and useful illustrated chronologies full of the ephemera of an artist’s life. Since the catalogue is completely bilingual (though I assume all the texts were originally written in French), I decided to concentrate on the translations to see how they stood up to a variety of complicated texts. And I was impressed. Ray Ellenwood is Professor Emeritus, Senior Scholar, at York University. [email protected] Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|