|

Colleen Skidmore

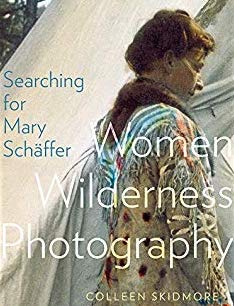

Searching for Mary Schäffer: Women, Wilderness, Photography Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press, 2017 448 pp., 60 + colour illus. $34.95 (paper) ISBN: 9781772122985 Mary T. S. Schäffer, the Philadelphian botanist, adventurer, and photographer, is perhaps best known for being one of a handful of women to have braved the back country of the Canadian Rocky Mountains at the turn of the twentieth-century. While her life and work have taken on particular resonance in Banff, where she settled later in life, they have also attracted attention in Canada and the United States more broadly, where her writing and photographs continue to be the source of much popular and scholarly attention. In 1992, for instance, she caught the eye of Lucy Lippard, who identified one of Schäffer’s photographs as the impetus behind her important edited volume Partial Recall: Photographs of Native North Americans. And as recently as 2011, Schäffer’s travel photographs were the subject of a publication by Michale Lang entitled An Adventurous Woman Abroad: The Selected Lantern Slides of Mary T. S. Schäffer. However, though Schäffer may be widely recognized, it remains extremely difficult, as with all authors who make their fame through travel writing, to separate the persona from the person, the tale from the actual event. Yet this is the ambitious goal Colleen Skidmore sets herself in Searching for Mary Schäffer: Women, Wilderness, Photography, the latest addition to the University of Alberta Press’ Mountain Cairn series. In the author’s own words, this book “aspires to ask new questions and to tell new stories with new or more fully formed characters” (45), so that the reader may gain a different perspective on a woman whom others have built into a great Canadian heroine. The project rests firmly on the work Skidmore undertook as the editor of This Wild Spirit: Women in the Rocky Mountains of Canada (2006), an anthology of women’s writing also featured in the same series. What Skidmore accomplishes with Searching for Mary Schäffer is primarily an insightful reinvestigation of Schäffer’s life by way of thorough archival research. Already familiar with the reams of correspondence, manuscripts, and photographs that make up Schäffer’s fonds in the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Skidmore was also able to locate the extant documents of Mary (Molly) W. Adams, Schäffer’s long-time travel companion, whose diaries and letters were still in the hands of her descendants. Using her substantial talents as an evocative writer, Skidmore animates this archival material, bringing to life the personalities of these two women, while adamantly reiterating the futility of seeking out a “genuine” Mary Schäffer. This is not the impassioned adulation of a devoted admirer, although Skidmore’s respect for Schäffer’s nerve does come through. Rather, it is a careful and much-needed re-evaluation of a well-known but little interrogated icon. The result is a superbly illustrated monograph that complicates the legend of Mary Schäffer by insisting on primary sources, by looking beyond her best-known work, and by focussing inquiries along the three thematic lenses of women, wilderness, and photography. It must, however, be mentioned that Skidmore’s approach to these politically laden themes is largely bio-historical, and some seminal theory falls by the wayside. Key names like Abigail Solomon-Godeau and Linda Nochlin are surprisingly absent from this feminist visual study, and the work of Joan Schwartz on archives and James R. Ryan on colonial photography, for instance, might have been used more extensively. There is no question, however, that this book makes a significant contribution to the field of Rocky Mountain studies, and others, too, will find use in its probing reflections on the unreliability of authorial voice, the subjectivity of photography, and settler/indigenous relationships. The first two of these topics are central to Skidmore’s guiding assertion that “Schäffer’s work is a mixture of fact and invention” (135), a claim she supports by recourse to Margaret Atwood’s musings on the writer’s persona and Stephen Jay Gould’s concept of “literary bias.” As for the treatment of Schäffer’s interactions with First Nations peoples, much energy is focussed on her portrait of the Beaver family, whom she met while in Îyârhe Nakoda territory, and whose members Skidmore attempts to track through governmental censuses, revealing the spottiness and gaps of those records that document Indigenous lives. As an answer to twentieth-century critics, such as Julia V. Emberley who condemn Schäffer’s work as racist opportunism, Skidmore quotes Louis Owens, a novelist and scholar of Indigenous and Irish-American descent: “It seems that a necessary, if difficult, lesson for all of us may well be that in giving voice to the silent we unavoidably give voice to the forces that conspire to effect that silence” (179). That Schäffer was a white woman who made use of her colonial privileges is certainly an important issue to consider, but what Skidmore finds far more problematic is the fact that her photographs have since been appropriated by the tourism industry, academia, and other interests to make generalist claims that do not shed further light on the actual people involved. Beyond addressing such sensitive subjects, Skidmore does an excellent job of signposting further reading. Her bibliography alone represents an important resource to anyone carrying out research on Canadian travel literature, gender studies, photography, or national parks. Skidmore begins her book by addressing the ethical dilemmas of reprinting private or unpublished material and of writing women’s biographies, bemoaning the fact that “women’s personas … are rarely reconstructed without attention being paid to the woman’s intimate relationships, especially marriage (or lack of it)” and that “most writers of Schäffer’s life refer to her by her first name only … [which is] jarring and presumptuous” (41). Much of the opening chapter is dedicated to a survey of the praise and criticisms directed at Schäffer over the years. In particular, Skidmore touches on the problems of various republications of Schäffer’s work, such as E. J. Hart’s A Hunter of Peace (1980), which included a verbatim transcript of Schäffer’s 1911 memoir Old Indian Trails of the Canadian Rocky Mountains, but failed to maintain the original relationship between the writing and its photographic illustrations. Skidmore also remarks that few scholars who have accused Schäffer of being affected, bourgeois, or colonial in her attitudes have taken the pains to look much beyond Schäffer’s published output, which they often take to be of a documentary nature rather than memoirs. “Over-reading photographs,” Skidmore warns, “is easily done; but, like reading narrative literally rather than literarily, it leads to unsupported and misleading claims, and strips the image of the nuances and complexities of looking and looking back that are at play” (177). Skidmore makes it clear that her aim is not to make Schäffer either a whipping post or a saint, but to provide readers with a more nuanced understanding of her as someone who worked just as much within as against gender and racial conventions, and whose many projects—whether botanical publications, survey maps, or photographic essays—should be read as collaborative endeavours that encompass a far greater cast of characters than is usually acknowledged. The introduction is followed by four geographic and roughly chronological chapters, each headed by a letter to or from Schäffer—an editorial choice that allows us to imagine Skidmore herself sifting through hundreds of pages of correspondence. Schäffer is first introduced to the reader as the wife of the eminent botanist Charles Schäffer, thanks to whom she is initiated into Philadelphia’s many erudite groups, from the Academy of Natural Sciences to the Photographic Society and the Geological Society. It is her husband’s research and eventual death that brings her to the Rockies, year after year, to complete the work they began on alpine flora. The next two chapters are devoted to her subsequent expeditions into the mountains and her growing association with Molly Adams, a fellow American whose bushwhacking enthusiasm matched Schäffer’s own. This is the Schäffer most are familiar with, the one who trekked through the brush beyond the Canadian Pacific tracks, who befriended Îyârhe Nakoda tribes, and who located the mythic Chaba Imne lake (now Maligne Lake), as told in her highly acclaimed adventure account, Old Indian Trails. Here, Skidmore stresses how Schäffer’s best-known work would not have been possible without the help of Adams, whom Schäffer herself credited for her photographic contributions to Old Indian Trails. The assistance received from different mountain guides the women hired is also highlighted by Skidmore, as is that of the many Indigenous peoples Schäffer and Adams encountered along their travels. The final chapter is concerned with the four-month trip Schäffer and Adams made to Japan in 1908. In this vastly different setting, the two women’s interests appear to have been more ethnographic than botanical or geographic, with the pair spending a good few weeks recording the Ainu and the Atayal, Japan’s aboriginal communities. The voyage ends in tragedy with the death of Adams, and Schäffer returns home alone to embark on other notable, but less famous adventures. Such is Schäffer’s life as Skidmore tells it, and this makes for a pleasant read, to be sure. However, despite claims that the book “proceeds from Schäffer’s visual practices, particularly photography,” (45) the more avid photography historian will be left hungry for more. The medium itself, along with the various formats Schäffer favoured (the print, the lantern slide, the book illustration) are discussed rather summarily. This is perhaps due to the fact that Skidmore’s principal resources are personal archives, which speak more to life events than to photographic decisions. Still, especially because coloured slides were such a point of pride for Schäffer, it would have been interesting to get more of a sense of how these images were put to use by their maker. The writings of Elizabeth Edwards, Janice Hart, and Geoffrey Batchen—scholars who are all concerned with the “objecthood” of photography—might have helped shed more light on how the material specificity of Schäffer’s pictures influenced their reception and meaning. That Skidmore is lean on photographic theory is less of an issue than her choice to stick very closely to Schäffer herself, which means that the socio-historic reality of the Canadian West at the turn of the century—a cultural landscape that is well worth exploring—is relegated to background scenery. Had Skidmore instead opted to present context through the life of Schäffer, as she does in the brief section on the rivalry that opposed pictorialist and realist photographers in the late-nineteenth-century, the book would have read less like a straightforward biography. Rebecca Solnit accomplished something of this sort in her book River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West (2003), in which she interprets the massive social shifts of late-nineteenth-century California using the renowned photographer as a lens. Moreover, besides Adams’ photographs, which are virtually undistinguishable from Schäffer’s, Skidmore does not bring in many comparative images by other female photographers who were also active in the Rockies at the time. The reader is afforded two small illustrations from Julia Henshaw’s Mountain Wild Flowers of Canada (1906) and one snow-capped peak from Henrietta L. Tuzo, which was pasted in one of Schäffer’s albums. The prolific Mary M. Vaux, who is mentioned several times in the text, is only granted two photographs that, in any case, present Schäffer as their subject. More could have been included here to give a greater sense of Schäffer’s position among her peers. These quibbles aside, Searching for Mary Schäffer does accomplish the revisionist mission it set out to achieve. Skidmore’s language is compelling and clear, and when she takes the time to slow down her storytelling and provide an in-depth analysis of an image, it is done with brilliance. This is especially true of her handling of the striking cover photograph, She Who Coloured Slides, a hand-tinted glass slide that Schäffer painted and that portrays her, but which was taken by Adams, and which displays a buckskin coat skilfully made by an unknown Métis woman. As such, this image serves as a fulcrum for Skidmore’s various reflections concerning Schäffer’s self-presentation, the impact of visual mediation on her work, her conception of the Rockies as a “peopled wilderness,” and her interactions with other women and Indigenous peoples. Skidmore’s readers will be left not only with an alternate interpretation of Schäffer’s life and work, but with useful strategies for tackling the mythic auras of other figures that loom large in the public imaginary. Stéphanie Hornstein is a PhD student in the Interuniversity Doctoral Program in Art History at Concordia University and an FRQSC-funded scholar. [email protected] Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|