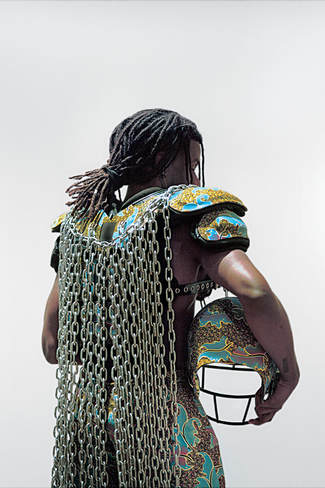

Esmaa Mohamoud, Untitled (No Fields), 2018, ink-jet print. Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects and the artist. Here We Are Here: Black Canadian Contemporary Art, May 12 to September 16, 2018, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Curators: Dr. Silvia Forni, Curator of African Arts and Culture, ROM; Dr. Julie Crooks, Assistant

Curator, Art Gallery of Ontario; and Dominique Fontaine, Independent Curator.

|

From Africa to the Americas: Face to Face, Picasso Past and Present

Curator for the Montreal adaptation: Nathalie Bondil, Director General and Chief Curator of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; assisted by Erell Hubert, Curator of Pre-Columbian Art, MMFA Organized by the Musée de quai Branly—Jacques Chirac, in collaboration with the Musée national Picasso-Paris, and adapted by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts Here We Are Here: Black Canadian Contemporary Art Curators: Sylvia Forni, Julie Crooks, and Dominique Fontaine; assisted by Geneviève Goyer-Ouimette, Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Curator of Quebec and Canadian Contemporary Art (from 1945 to Today), MMFA Organized by the Royal Ontario Museum and adapted by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal May 12, 2018 to September 16, 2018 In the early weeks of May, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) welcomed its patrons and a series of special guests from various Black Canadian communities to the opening reception of two exhibitions: From Africa to the Americas: Face to Face, Picasso Past and Present and Here We Are Here: Black Canadian Contemporary Art. These exhibitions were presented side by side in a continuous layout. The Picasso exhibition presented an overview of Western attitudes regarding art from Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, and purported to tell “the story of ‘the museum of the Other,’ from the legacy of a colonial world to its current redefinition as a globalized one.”[1] The exhibition also featured several contemporary African diasporic artists, thus placing them in direct conversation with the colonial histories broached. Here We Are Here, on the other hand, called into question established perspectives on Blackness in Canada through the work of eight contemporary artists—Sandra Brewster, Michèle Pearson Clarke, Charmaine Lurch, Esmaa Mohamoud, Bushra Junaid, Gordon Shadrach, Sylvia D. Hamilton, and Chantal D. Gibson—who “blur the longstanding perception that Black bodies belong on the edge of Canadian history.”[2] This iteration of the exhibition, which was initially presented earlier in the year at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto, also included three Montreal artists: Eddy Firmin, Manuel Mathieu, and Shanna Strauss. Here We Are Here aims to affirm the longstanding histories of Black Canadians and correct the erroneous notion that Black people are necessarily immigrants or newcomers in Canada.[3] Let us address the elephant in the room right away. Like me, you may be wondering why these two shows are being presented together and why visitors are compelled to view them by starting with From Africa to the Americas and ending with Here We Are Here. This implies that there is some kind of narrative current threading the two exhibitions together, yet this relationship is not clearly explained to the public. What is made clear, however, is that they were produced separately. From Africa to the Americas was arranged by the Musée du quai Branly—Jacques Chirac with the Musée national Picasso-Paris, and modified with new texts and additional artworks by the MMFA for its appearance in Montreal. Here We are Here was developed by the ROM and is the first major exhibition ever presented by a large-scale Canadian institution featuring exclusively Black Canadian artists. This exhibition stems from the Of Africa Project, and was initiated by the ROM as a means of repairing its relationship with Black Canadian communities following the controversial events surrounding the exhibition Into the Heart of Africa (1989).[4] While a re-examination of the relationship of Picasso and his contemporaries to African art is certainly pertinent and necessary, it seems curious for this conversation to be paired with an exhibition focused on contemporary Black Canadian art and history, especially when no clear context has been given to the relationship between these two critical endeavours. Given that From Africa to the Americas is presented as a critical rereading of Picasso’s artwork and an homage to historical African art, it is disheartening to note that, once more, African diasporic art is forced to play second fiddle to the career of a prominent white, male, European artist. Beyond this disappointing curatorial choice, this presentation by the MMFA offers many discussion points. From Africa to the Americas is divided into seven and a half spaces and, from the onset, the exhibition claims that its aim is to examine Picasso’s work from a critical perspective, and to consider his practice within the contexts of colonialism, naming the histories both of so-called “primitive” art and of transatlantic slavery in the wall texts. The first room, titled “Preface: Obscurationism in the Age of Enlightenment,” drives home this point by presenting the work of contemporary African artists exclusively; featured artists include Yinka Shonibare MBE, Mohau Modisakeng, and Omar Victor Diop. The choice to introduce the exhibition with contemporary African art is powerful and asserts that the exhibition will not fit within the realm of “easy listening art,” which Adrian Piper defines as “art that is meant to be looked at rather than seen.” In her words, this kind of art “does not make trouble; instead it makes nice.”[5] Indeed, the political charge of this room demands discomfort and engagement from its viewers. While the space makes a powerful statement through the absence of European artists, the mention of Canadian slavery—though groundbreaking, considering the ongoing refusal of various institutions to acknowledge this history—seems misplaced, especially in the absence of any Black Canadian art in the space.[6] The next several spaces offer an overview of Picasso’s artistic career and life from the late nineteenth century onward, and underline a series of seemingly disparate themes, including evolving terminology, fetishism, Picasso’s tumultuous love life, Minotaur and African mythology, upcycling, and canonical appropriation. Many of these spaces feature vitrines displaying books and important texts accompanied by detailed timelines that juxtapose Picasso’s life with continental African and Black diasporic histories. These underline a variety of historical events ranging from the Conférence de Berlin (1884–85) to the 1960 declarations of independence by seventeen African countries. The curatorial team and advisory committee have made clear efforts to provide detailed information and ample context for the African and Indigenous artworks featured. Indeed, only very few items are left without didactic panels. The exhibition thus presents a complex combination of artwork and histories and positions a myriad of mid-century African, Indigenous, and contemporary Black diasporic artists, including Montreal’s own The Woman Power collective and Moridja Kitenge Banza, African-American artist Mickalene Thomas, and South African artist Zanele Muholi, alongside Picasso and his white comrades. Throughout the exhibition, however, there are some notable, and perhaps telling, slippages. In the fourth room of the exhibition, titled “‘Exquisite Corpses’ and Transformation”— the didactic text accompanying a Taíno “anthropomorphic axe blade” (1200–1492) first asserts that the Taíno, the Indigenous people of the island of Hispaniola (among other Caribbean areas)–were “decimated” by Columbus, only to aloofly note later that the Taíno are “now vanished.” This phrasing muddles the fact that this “disappearance” is the direct result of the “deadly encounter” with Columbus. In fact, recent studies have found that the Taíno are still present.[7] The insistence on erasing Taíno people from the contemporary moment falls in line with ongoing settler-colonial efforts to make invisible Indigenous presences across the globe. The language used here marks a disconnect from the exhibition’s introductory texts, which boldly mention the world-shifting impact of the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), when Saint-Domingue (formerly Hispaniola) was reclaimed by enslaved Africans and renamed Haiti. The egregiously dismissive and misleading account of the history of the Taíno people throws into question the intentions of this exhibition to “[decolonize] the colonial gaze,” as the MMFA website repeatedly states. The following space, “1946 to Today: Towards the Decolonized Gaze,” also features questionable commentary. In this area, a text panel seems to imply that Picasso’s friendship with the prominent Martinican scholar, poet, and activist, Aimé Césaire, touted as the father of Négritude, is somehow a sign of his moral character and essentially pulls the “Black friend card,” a strategy often used to mask racist behaviour or to justify a lack of accountability for colonial relations.[8] The panel does little to discuss if and how Picasso may have leveraged his power and privilege to undo his part in the mistreatment of African art. Instead, it seems to excuse Picasso and his white contemporaries from the impact of their actions, and thus serves to reflect the underlying tone of the exhibition. Furthermore, this panel repeats another recurring theme in this exhibition. Many of the men featured in From Africa to the Americas are known to have been unapologetically sexist and abusive. As noted by scholars Michel Hausser and Véronique Halpen-Bessard, Corps perdus, the collaboration project between Picasso and Césaire mentioned in this wall text to bolster the painter’s credentials, is but one example of the demeaning treatment of women in these men’s work.[9] Meanwhile, the exhibition features only one mention of Suzanne Césaire, whose oft-overlooked work as a writer, teacher, scholar, anti-colonial and feminist activist is nowhere to be found in this show, despite her important contributions to both the Négritude school of thought and the history of surrealism.[10] A single portrait on the back cover of a book introduces her simply as Aimé’s wife. The final exhibition space, “Postface: Atlas Fractured and the Traffic of Worlds,” discusses the appropriation of Eurocentric canons and aesthetic devices by contemporary artists such as Kehinde Wiley, Samuel Fosso, and Theo Eshetu, who insert Black narratives into these white spaces. Yet, there is little critical engagement here with the history of museum institutions in relation to African art. Indeed, beyond Susan M. Vogel’s video Fang: An Epic Journey (2001), there is minimal discussion of these institutions’ role in the treatment of African art as ethnographic and “primitive.” It is disappointing to note that the exhibition, which presents itself as a critical rereading of Picasso’s body of work aimed at underscoring the power and beauty of African art, does not do the work of decentering whiteness or Picasso. This curatorial approach repeatedly contradicts the exhibition’s ostensible critical intent. While African art history could have been the focal point, it is overshadowed by Picasso, whose life events are centred as the driving force behind the themes discussed. Vogel’s video is featured in a transition area following the final room of From Africa to the Americas. At this point in the exhibition, viewers are presented with a souvenir shop rather than a space dedicated to bridging the gap between Picasso and Black Canadian contemporary art, or to explaining the choice to present these shows together. This curatorial choice does little more than add to the general oddity of the experience, as visitors must walk through the entire Picasso exhibition and a small store in order to view Here We Are Here, regardless of which exhibition they came to see. Any discussion about how—if at all—these histories are connected is abruptly cut off. The lack of explanation for this choice implies that the exhibitions are connected simply because they both feature Black people, which further undermines the purported critical gaze of the Picasso exhibition and undercuts the historical importance of Here We Are Here. Crucially, there is a missed opportunity here to locate African art history as the narrative current within which Picasso inserted himself. Given the significance of Here We Are Here, the combination of the two exhibitions is unnecessary and unfortunate. This choice creates a power dynamic positioning Here We Are Here as an afterthought or by-product of Picasso’s life and work. Here We Are Here reflects a rich and complex Black Canadian art history, one that exists despite, and not because, of histories of slavery and colonialism. Fittingly, among the most impactful of the pieces included in Here We Are Here is Michèle Pearson Clarke’s three-channel video, Suck Teeth Composition (After Rashaad Newsome) (2017). The didactic panel notes that sucking teeth is “an everyday oral gesture shared by Black people of African and Caribbean origin and their diasporas, including those living in Canada.”[11] Originating in West Africa, this sound signifies a range of negative emotions that, in Clarke’s video, include “the anger and pain of Black people living in Canada, where the ‘multiculturalism’ veneer denies the racism that many experience in their daily life.”[12] The familiar sound of Black discontent echoes against the stark white walls of the gallery space, attracting viewers (and listeners) like moths to light. Black figures of various genders and hues stand sometimes facing the camera and at times turning away from it, making their disgruntlement known through the simple, yet unmistakable sound of sucking teeth. One of the final pieces shown in Here We Are Here is the exhibition’s namesake, the work of Sylvia D. Hamilton, a prominent figure in Black Canadian art and history. Her installation Here We Are Here (2013–2017) features a single projection of waves over a printed poem written by the artist, with an audio track of her voice reading the names and ages of hundreds of free(d) and enslaved Africans, as well as Black Loyalists, whose names are also listed on six tall panels on an adjoining wall. As wall text explains, these names were taken from the “public archives of Nova Scotia—T.W. Smith’s The Slave in Canada (1899), Sir Guy Carleton’s Book of Negroes (1783), and the War of 1812 Black Refugee List.”[13] The installation also includes vitrines of Blackface memorabilia, as well as artefacts and archives chronicling the history of Black Canadians, each accompanied by Hamilton’s written statements. Hamilton’s work, along with that of all the other artists featured in the exhibition, emphasizes the rich and complex history of Canada’s longstanding Black communities. Here We Are Here makes the necessary statement that issues of anti-Blackness in Canada and of appropriation in the art world are far from resolved, and offers a glimpse of the crucial work that artists and curators of colour across the country continue to do to enact change within museums and cultural institutions.[14] Together, these two exhibitions could have engaged in interesting and necessary discussions to complicate our understanding of Blackness, decolonization, and what institutional change means beyond superficial representation. What would it have meant for the MMFA to choose to decenter whiteness and focus on the importance of Here We Are Here? What would it have meant instead to begin with Black Canada? This groundbreaking exhibition should have been given the space and respect to stand alone, as had originally been intended, so that its clear message and obvious power could reverberate unabated in the minds of visitors. Joana Joachim is a PhD Candidate in Art History at McGill University. [email protected] [1] “From Africa to the Americas: Picasso, Face-To-Face, Past and Present,” Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, https://www.mbam.qc.ca/en/exhibitions/on-view/picasso (accessed May 8, 2018). [2] “Here We Are Here: Black Canadian Contemporary Art,” Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, https://www.mbam.qc.ca/en/exhibitions/on-view/here-we-are-here (accessed May 8, 2018). [3] Ibid. [4] “Of Africa,” Royal Ontario Museum, https://www.rom.on.ca/en/of-africa (accessed June 17, 2018; Shelley Butler, Contested Representations: Revisiting Into the Heart of Africa (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011). [5] Adrian Piper, “Goodbye to Easy Listening” in Adrian Piper: Pretend (New York: John Weber Gallery, 1990). [6] Charmaine Nelson, Ebony Roots, Northern Soil: Perspectives on Blackness in Canada (Newcastle: Cambridge Publishings, 2010), 16. [7] “Anthropomorphic ax blade (1200 – 1492),” didactic label, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, From Africa to the Americas: Face to Face, Picasso Past and Present. 2018; Samuel Meredith Wilson, The Indigenous People of the Caribbean (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1997); Tom Kirk, “Ancient Genome Study Identifies Traces of Indigenous ‘Taíno’ in Present-Day Caribbean Populations,” University of Cambridge, February 19, 2018, https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/ancient-genome-study-identifies-traces-of-indigenous-taino-in-present-day-caribbean-populations (accessed August 20, 2018). [8] “Aimé Céasaire: Sa biographie,” Fondation Aimé Césaire, http://www.hommage-cesaire.net/spip.php?rubrique8 (accessed June 17, 2018); Shae Collins, “Why ‘I Have Black Friends’ Is a Terrible Excuse for Your Racism,” Everyday Feminism, June 17, 2018, https://everydayfeminism.com/2017/03/black-friends-excuse-for-racism (accessed August 20, 2018). [9] Michel Hausser, “Du Soleil au Cadastre,” in Soleil éclaté, Mélanges offerts à Césaire (Türbingen: Gunter Narr Verlag, Ed., 1984) 187; Véronique Halpen-Bessard, Mythologie du féminin dans l’œuvre poétique d’Aimé Césaire. Contribution à l’étude de l’imaginaire césairien, PhD Dissertation, Université des Antilles, Fort-de-France, April 1999, 315. [10] Daniel Maximin, Suzanne Césaire: le grand camouflage. Écrits de dissidence (1941–1945) (Le Seuil: Paris, 2009). [11] “Suck Teeth Composition (After Rashaad Newsome),” didactic panel, Here We Are Here: Black Canadian Contemporary Art, Royal Ontario Museum, 2018. [12] Ibid. [13] Sylvia D. Hamilton, “Naming Names,” didactic panel, Here We Are Here: Black Canadian Contemporary Art (2013-2017). [14] Michael Maranda, “Hard Numbers: A Study on Diversity in Canada’s Galleries,” Canadian Art (April 5, 2017) https://canadianart.ca/features/art-leadership-diversity (accessed June 23, 2018) Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|