|

Bodies in Translation: Age and Creativity

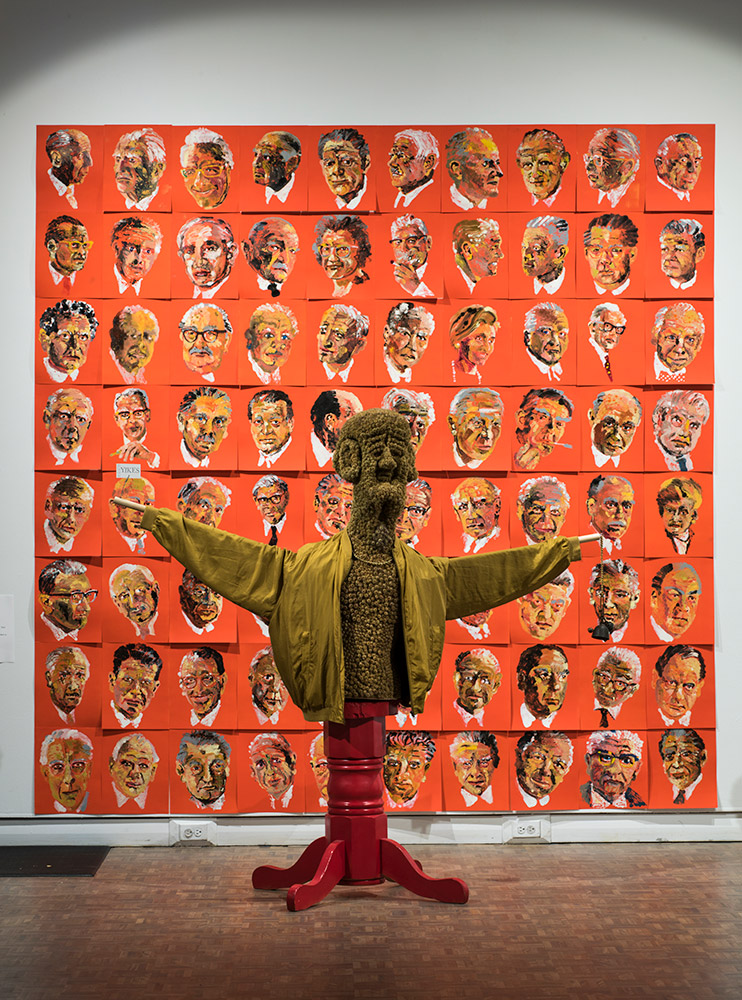

Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery September 9, 2017- November 12, 2017 Co-curated by Eliza Chandler, Lindsay Fisher, and Ingrid Jenkner According to Carmen Papalia, a blind social practice artist, “it's about time that patrons of the museum get an experience, besides a detached and alienating one, in return for their patronage” (Papalia). The exhibition Bodies in Translation: Age and Creativity, held at the Mount Saint Vincent University (MSVU) Art Gallery from September 9th to November 12th, 2017, provided the kind of experience Papalia calls for. Bodies in Translation was a collaborative effort of the MSVU Art Gallery, the SSHRC-funded project “Bodies in Translation: Activist Art, Technology, and Access to Life,” and the Nova Scotia Centre on Aging at MSVU. In both its artistic content and curatorial strategy, it proposed an alternative approach to the deferential and limiting ways visual art is typically selected for and displayed in galleries. Co-curated by disabilities scholar Eliza Chandler, primary investigator of “Bodies in Translation” Lindsay Fisher, and MSVU Gallery Director Ingrid Jenkner, its focus was on accessibility as a critical framework for reconsidering the function of the gallery. The exhibition featured the works of seven Maritimes-based artists: Cecil Day, Michael Fernandes, Karen Langlois, Onni Nordman, MJ Sakurai, George Steeves, and Anna Torma. All addressed various facets of aging as an artist, including the stigma surrounding disability, injury, sexuality, illness, and death. The approach to curation was animated by the critical potential of gallery access. In her curatorial text, Chandler explained that there is an ongoing interest in interrogating, rather than taking for granted, the ways that bodies and art interact: "Buoyed by the lessons passed down from disability arts, we, the curators of this exhibition, specifically sought out work by aging artists who wittingly, subversively, subtly, whimsically, intimately, and culturally animate the particular interaction between aging bodies and the artistic process…The binding thread between these works is the provocation for us to consider the dynamic ways that aging invigorates art-making as well as the art that is produced." (“Bodies in Translation”) In this sense, the curation of Bodies in Translation “cripped” the gallery space for the duration of the show — and beyond.[1] As Jenkner has acknowledged, the preparations for mounting Bodies in Translation have led to a commitment to systematically transform the MSVU Art Gallery’s approach by implementing accessible presentation practices for all future exhibitions. MSVU Art Gallery’s engagement with institutional accessibility in the arts isn’t unprecedented nationally or internationally, as the Deaf and disability arts movement has had global presence since the 1990s.[2] However, it is locally exceptional, as Deaf and disability arts have remained under-developed in the Atlantic provinces of Canada (Jacobson 33). Being able-bodied has extended to me the privilege of relatively unchallenging access to art spaces. However, as someone with poor eyesight, I found that the curatorial approach of Bodies in Translation resonated with me; it deepened my conception of what it means to be a “viewer” of art, challenging assumptions surrounding art-making in relation to aging and disability. The exhibition provided a model for presenting art in more accessible ways by providing gallery attendants to aid visitors during open hours, flexible seating, American Sign Language interpreters at events, artist-described audio guides, the option to touch some of the art, and didactic materials available in large font and Braille. Among the pieces that invited visitors to use their tactile senses was Onni Nordman’s Scarecrow Among the Chancellors (2017), in which seventy monotype portraits of German chancellors hanging in a grid on the wall were accompanied by a life-size figure made of thousands of burrs from the burdock plant. The figure had a heavy red table leg in place of his lower half, and his rigid wooden arms were outstretched, scarecrow-like. Nordman described him as “weathered survivor before a monument of top dogs… experiencing a moment of status vertigo.” Although I was able to first experience the visual aspects of the piece, I decided to commit myself to the realm of touch and I closed my eyes. I began to explore the burdock sculpture, the exposed chest and face made entirely of the velcro-like burrs. In contrast, the scarecrow was wearing a smooth, silky zip-up jacket. His height was similar to mine, although his proportions were unusual; his barrel-like torso was oversized and his outstretched arms were extremely long. As I moved my hand along one of the wooden limbs, I noticed a detail I had missed when I took in the work with my sight: he was holding a bell and it rang when I touched it. Perhaps this aged scarecrow might have acted as a guard for the chancellors behind him, the bell warding off unfavorables such as myself. Although he might not possess the clout of those depicted in the portraits, he was resilient and bore the mark of distinction in his robust and rough form. The monotypes also gave some tactile form to an otherwise two-dimensional medium as the features of the chancellors could be faintly discerned by touching the stucco-like raised paint. Tactility is even less likely to be associated with printmaking than with painting, but it was incorporated in an innovative way in Cecil Day’s linocuts Grasses, Fall Cinnamon Fern, and Winter Goldenrod (2016). The plants are portrayed as stark black silhouettes against a white background. Directly in front of the prints on the wall, the printing plates used to create the images are displayed on a table. Gallery visitors were invited to use their own hands to feel the relief textures and patterns of the images, which would otherwise remain trapped behind glass and inaccessible to the visually impaired. Day’s work confronts us with the fact that the visuality of printmaking relies entirely on a textural process. The choice to display the plates alongside the finished prints deconstructs the supremacy of the visual art object over the sensuous process artifact. In the described audio accompanying the work, Day said that her images are analogous to “thinking of death and regeneration” as the earth is “a repository for the dead: plants, birds, animals, humans; but also the place of their regeneration in the rich array of grasses and groundcovers.” As arthritis develops in her hands, Day has begun to make black-and-white prints, discarding colour as superfluous in favour of a simpler process. In both her method of production and in her imagery, Day confronts the poetics of aging and the reality of mortality. Although audio description is a fairly conventional form of accessibility support in galleries and museums, it is unusual that the artists themselves provide the scripts. As independent curator Amanda Cachia has written, artist-described audio can become an extension of the creative process, prompting critical thinking “about a fuller spectrum of audiences, and how they might access…art beyond the ocular...adding new dialogical layers to a work that is predominantly visual or aural” (29). The artist-described audio in Bodies in Translation was dynamic, and enhanced both sighted and non-sighted art experiences. Michael Fernandes’s piece Group On (2017) toys with linguistic associations and everyday objects. He claims that “as I grow older, my work has become less obvious and revisits the mundane with an eye to simplicity...Day by day, life finds me less critical, more playful.” This work was made up of what Fernandes describes as “assistive devices”: a spring-loaded cane, running shoes size 9 ½ M, a 25lb dumbbell with skipping rope, ping-pong paddles with taped ball, etcetera. An audio component to the installation, “Michael, Michael, Michael” plays on headphones mounted on the wall beside the objects. As I listened to the described audio, I sat some distance away and noted discrepancies between the work’s description and what I saw; for instance, a spring-loaded shower curtain was identified as a “trusty spring-loaded walking stick.” He also mentioned that there was a banana present as one of his assistive devices. This was notably missing. Why was there no banana? Was it eaten? Was it ever really there? Perhaps Fernandes meant to demonstrate that aging can incite new forms of interpretation, resourcefulness, and creativity, or he toys with the signifiers associated with the care of aging bodies through an absurd refusal to use the objects as expected. It’s only through the multi-sensory exploration of Group On via the accessibility supports that one comes to notice its subtle inconsistencies. As Cachia anticipated, the artist-described audio added a layer of meaning to the work; Fernandes made visitors consider their own limited perspective as embodied subjects, regardless of age or disability status. As I experienced the works in the show through a multi-sensory mode, I began to confront internal anxieties surrounding vision degradation, even though I am still young by both social and physiological definitions. Yet Bodies in Translation offered solace by demonstrating that visuality does not have to be given primacy as a vehicle for experiencing art. The use of accessibility strategies made “visible” the stale reliance on sight in the gallery and challenged the stubborn paradigm of acceptable gallery conduct. The show reimagines how different bodies, abilities, and senses are valued in society, drawing attention to the vitality with which aging artists create. The exhibition gave visitors permission to touch the art, and as a result, the art was able to touch them in unexpected ways. Jolee Smith is a graduate student in art history at Concordia University. As an undergraduate, they pursued a research internship, focusing on Deaf and disability arts in Canada and accessible curatorial practices. [1] “Crip” is a term of reclamation used between disabled people to signify identity, culture, and community [...] to open up with desire for the ways that disability disrupts” (Chandler, “Creatively Engaging”). [2] Since the 1990s, activists, artists, and academics involved in the disability rights movement have shifted from a materialist framework (which focused on economic equity for people with disabilities) to a sociopolitical analysis (which includes the development of art, culture, and media of people with disabilities) (Meekosha 48-49). Works Cited Cachia, Amanda. “‘Disabling’ the Museum: Curator as Infrastructural Activist.” Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, Vol 2, No 4. (2013). http://cjds.uwaterloo.ca/index.php/cjds/article/view/110/227, (accessed Mar 10, 2018). Chandler, Eliza. “Bodies in Translation: Age and Creativity.” Bodies in Translation: Activist Art, Technology, and Access to Life. Halifax: Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery, 2017, http://bit.mat3rial.com/bodies-in-translation/, (accessed July 14, 2018). Chandler, Eliza. “Creatively Engaging: Disability Arts, Aesthetics, and Accessibility” (lecture, Halifax Public Library, Halifax N.S., September 21, 2018. Jacobson, Rose and Geoff McMurchy. Focus on Disability & Deaf Arts in Canada. Canada Council for the Arts, 2010. canadacouncil.ca. Accessed Mar. 10, 2018. Jenkner, Ingrid. “Foreword.” Bodies in Translation: Activist Art, Technology, and Access to Life. Halifax: Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery, 2017, http://bit.mat3rial.com/foreword/, (accessed July 14, 2018). Meekosha, Helen and Russell Shuttleworth. “What's So ‘critical’ About Critical Disability Studies?” Australian Journal of Human Rights Volume 15, 2009 - Issue 1: Special Issue on Human Rights and Disability. Papalia, Carmen. “A New Model for Access in the Museum.” Disability Studies Quarterly, Vol. 33 No. 3 (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v33i3.3757, (accessed Mar. 10, 2018). Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|