|

Rina Arya and Nicholas Chare, eds.

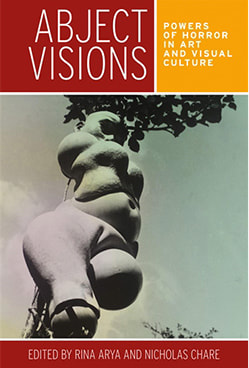

Abject Visions: Powers of Horror in Art and Visual Culture Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016 208 pp. 7 b/w illus. $31.31 (paper) ISBN: 978-0-7190-9629-7 Rina Arya and Nicholas Chare’s edited collection Abject Visions: Powers of Horror in Art and Visual Culture (2016) argues that the theory of the abject continues to be an enduring and productive site of thinking in contemporary visual culture. This volume developed out of Arya and Chare’s ongoing work on the subject, Arya’s Abjection and Representation: An Exploration of Abjection in the Visual Arts, Film and Literature (2014) and Chare’s Auschwitz and Afterimages: Abjection, Witnessing and Representation (2011). In Abject Visions, the editors gathered writing from eleven scholars who pursue this field of study and address the abject through the manifold contemporary arts. Although the majority of essays in this collection focus on the visual arts, Abject Visions develops a broad range of commentary related to cinema, literature, and performance art from the late-nineteenth century into the contemporary period. This collection proceeds from the model of abjection proposed in the germinal psychoanalytic theories of Julia Kristeva (1980–1982) and combines it with Georges Bataille’s concept of “base materialism” (1934–1970) and Judith Butler’s development of abjection as a strategy of performativity in which queer bodies constitute the abject figures of the heterosexual matrix (1993). Arya and Chare’s introduction to this volume provides a succinct summation of Kristeva’s well-known theory, which she laid out in her influential book Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (1980). Working within the Lacanian paradigm, Kristeva introduces a theory of psychic refusal that envisages a variety of abject bodily materials—a gamut of human excretions that divulge an often gruesome, frequently moist and disquieting underside to psychic formation. The editors note that Kristeva locates her frame in a modernist temporality, and much of the existing commentary on the abject in this book refers to a 1993 exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art entitled Abject Art: Repulsion and Desire in American Art, where four curators chose a selection of post-1945 artworks exploring the extreme limits of the abject body, primarily in terms of gender and sexuality. This exhibition included artworks dripping with bodily excesses, such as Robert Mapplethorpe’s Self-Portrait with Whip (1978), Eva Hesse’s Untitled (Rope Piece) (1969–70), and Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document (1974), many of which have come to represent our contemporary understanding of the abject—or at least what it looks like. As Chare and Arya point out in their introduction, this corpus of works, now largely familiar in twentieth-century art surveys, deals in our abject human materials and the horror provoked by these substances, which includes dirt, hair, excrement, menstrual blood, baby diapers, and perishing food (3). Indeed, as the contributors to this volume note throughout, the influence of the Whitney exhibition cannot be understated, yet the critique underscored here is at the level of representation, where the state of being abject is signalled by the visual character of these works (3). The Whitney exhibition explored abjection as it appeared in Judy Chicago’s Menstruation Bathroom (1972), a plastic garbage pail overflowing with used menstrual pads, or the disturbing force of dripping wax in Kiki Smith’s Untitled (1990), to name two more examples. To look at the range of art included in this exhibition attests to the importance of visuality in abject art: abject art shows abject stuffs, or rather, their invocation has become the signal of unequivocal abjection in art. In her contribution “Queering Abjection,” Jayne Wark is helpful in pointing out that the curatorial objectives of the Whitney exhibition slip between Kristeva’s fundamental work and the lesser-known ideas from Bataille’s 1934 essay “L’Abjection et les forms misérables” (1970). Bataille’s aims were sociological as opposed to psychoanalytic: “A critique of how the oppressors subordinate the oppressed through the mechanisms of exclusion and degradation that consigns them to the realm of abjection” (32). Bataille was echoed later in Butler’s advancement of the theory of abjection, which shows the abject at work in representations of homophobic, racist, and sexist acts, and the role they play in constituting unstable subjects. Wark explains that this is the context from which the exhibition at the Whitney emerged, and how it served to highlight gender and sexuality at a time when right-wing powers had launched an attack on bodies, particularly queer and female ones. Wark argues that the show’s curators were initially guided by Bataille’s socio-political conception of abjection, but, in the process of developing the exhibition, this perspective became conflated with the elements of repulsion and expulsion that were specific to Kristeva’s theory (33). As Wark sees it, the version of abjection that rose from this combination was a necessary counter-commentary on the context of the American Culture Wars, but it has confused a contemporary understanding of the abject in art since that period (33). John Lecht and Ernst van Alphen’s essays each point to this confusion of approach, showing how the condition of abjection (to be abject) and the operation of abjection (to abject) are mistakenly taken as one and the same. Van Alphen quotes Hal Foster to clarify: “To abject is to expel, to separate; to be abject on the other hand is to be repulsive, stuck, subject enough only to feel this subjecthood at risk” (121). The trend in art from the 1980s and 1990s reflected this conflation, as evidenced by works such as Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ (1987), which both represented the condition of abjection and provoked the viewer to react with disgust, thus rendering the work abject (121). Given that so many of the writers in this volume grapple with the theoretical ensemble of Bataille, Kristeva, and Butler, and that each, in their own way, comes to terms with the limitations imposed by the Whitney curators—that is to say what it means to name abject art as such—the essays as a collection may seem caught in a previous time. The art they discuss is difficult to disassociate from the identity politics and power abuses attendant to the 1980s and 1990s. On the other hand, it is worthwhile to note that our current social climate not only reflects, but intensifies these questions of identity and power. Although the present political condition does not figure among the essays in this volume, Arya and Chare note that “the curators of the Whitney exhibition also recognized the political potential of the abject” (4). The editors also assert the continuing relevance of the theory of the abject in aesthetic and social life. Some of the essays depart from the framework put in place by the Whitney Exhibition, going beyond the largely white canon that has become associated with abject art: Wark analyzes Métis artwork, and Rex Butler and A. D. S. Donaldson’s study of Chilean-Australian artist Juan Davila similarly introduces diversity. Writings from Kristen Mey and Estelle Barrett provide further contemporary perspectives that move beyond the Whitney show. Because so much of the corpus of abject art hinges on the visual aspects of the grotesque or shocking, much related criticism centres upon the challenges of representation. Barrett’s essay is grounded firmly in Bataille’s conception, contending that the operation of abjection—the ambivalence, attraction, and repulsion experienced by the viewer as they encounter art—is necessary to the aesthetic experience. As Arya and Chare point out, Barrett “[shifts] the focus from the reading of an artwork to an experiential encounter,” thus drawing the study of abjection into timely commentary on embodiment and the sensory in the reception of art, asking what is the force and function of abject works such as those produced by artist Catherine Bell, whose photographic and video works give rise to a complex of affective sensations (9). The jacket cover for Abject Visions promises a “path-breaking volume” and it is clear this collection marks a useful attempt to reread the abject in the present day, however difficult it is to leave behind the temporal period and theoretical ensemble from which the abject art movement was born. The scholars in this collection demonstrate how the abject in art destabilizes the field of identity and ruptures social and political norms through disturbing confrontations with the viewer. Arya and Chare, along with their contributors, are successful in developing a critical scholarly examination of the history of abject art. Yani Kong is a PhD candidate in Contemporary Art History and an instructor at Simon Fraser University, School for the Contemporary Arts. [email protected] Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|