|

Mark Cheetham

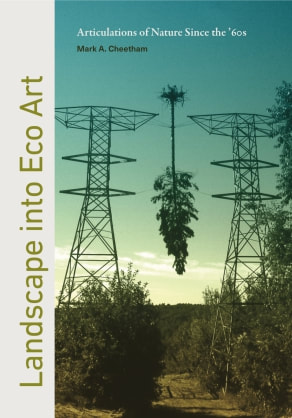

Landscape into Eco Art: Articulations of Nature Since the ’60s University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2018 256 pp. 27 colour; 36 b/w illus. $34.95 (paper) ISBN: 978-0-271-08004-8. In his wide-ranging new book Landscape into Eco Art: Articulations of Nature since the ’60s, Mark Cheetham proposes to consolidate the connections among three artistic practices: the historical tradition of nineteenth century landscape art, the conceptual explorations of land art, and the contemporary gestures of eco art both in and outside the museum. With deliberate titular reference to Kenneth Clark's Landscape into Art (1949), a text based on a series of lectures Clark gave as Slade Professor of Art at Oxford and republished to popular acclaim in 1976, Cheetham builds an argument meant to “complicate and ultimately justify the linkage of historical landscape as a genre, land art, and eco art [...] to address in new ways the questions of how ‘land’ comes in to eco art” (5). In doing so, Cheetham offers an appreciation for the dialogic connections across these various practices rather than accepting the art historical accounts of radical break and rejection that are often applied to the works of post-1960s artists. Whether you agree with the argument of ongoing continuity and interaction between these practices, or are more inclined to see breaks and disruptions, Cheetham's deeply researched and thoughtful book will give you much to consider. Rooted in his thorough understanding of Western philosophy of art and the growing field of environmental humanities, as well as in the literature on land art, earth art, and eco art, including recent works by Amanda Boetzkes and James Nisbet, Cheetham makes a convincing claim for the ongoing relevance of landscape art in all its forms. Such a claim of continuity requires the reader to accept criticisms of some of the most important writings on nature, land, and landscape in the last two decades, from W. J. T. Mitchell's Marxist takedown of an exhausted genre in Landscape and Power (2nd ed. 2002) to Timothy Morton's object-oriented ontological exegesis of “nature” (2007). Instead, the reader will find intriguing and sometimes surprising uses of the contemporary ideas of Mieke Bal, Lauren Berlant, Lorraine Code, Bruno Latour, and Michel Serres, as well as references to the current debates about the Anthropocene from scholars such as Donna Haraway and Jason W. Moore. Equally important are Cheetham's re-readings of the writings of nineteenth century natural philosopher Carl Gustav Carus, and the words of key land and eco artists. Indeed, one of the strengths of this book is the presence of artists’ writings and ideas, giving the text a deep grounding in the ideas and intentions of land and eco art-makers. According to Cheetham, eco art emerged in the 1970s in North America and Europe, becoming, by the 1990s, a vibrant and relevant practice that “questions our understanding and experience of nature” (1). As climate change and ecological collapse, at both the local and global levels, become increasingly urgent issues, artists and scholars are pressed to address the threats and concerns of a changing planet, employing interdisciplinary approaches to research and creation beyond the realm of the art world. Cheetham uses this book as an art historical forum to explore the connections between landscape art (and its imperialist impulses) and the land art of mid-twentieth century, embedded in the nascent environmental movement. Nevertheless, the bulk of the book focuses on key artists and artworks in the contemporary period, employing visual and discursive analysis to highlight their contributions to the period of anthropocenic disruption that we currently inhabit. The monograph includes five chapters, each with its own overarching theme supported by interesting reads of specific works by well-known contemporary artists such as Mark Dion, Basia Irland, and Tacita Dean. Chapter One, “Manipulated Landscapes,” explores Cheetham's thinking on the history and debates around landscape art's connections to later land and eco art practices. In the second chapter, “Beyond Suspicions: Why (Not) Landscape?” he takes this point further to discuss how postmodernism informed a negative engagement with the tradition of landscape in the works of 1960s and 70s land and eco artists. The third chapter, “Remote Control: Siting Land Art and Eco Art,” further expands on Cheetham's claims of the dialogic relationship between land and eco art through a discussion of the “siting” of these artworks in remote or urban places. Chapter 4, “Contracted Fields: 'Nature' in the Art Museum,” explores the ways that the museum has been and continues to be important in the art historical divide between the practices of land and eco art. In the last chapter, “Bordering the Ubiquitous: The Art of Local and Global Ecologies,” Cheetham discusses the importance of borders in eco art as a metaphor for the boundaries that must be overcome in both ecological thought and eco art history. While Cheetham begins and ends the book with reference to Olafur Eliasson’s celebrated The Weather Project (2003), a central example of eco art in Cheetham's conception and an inspiration for his research, the artist whose work and ideas inform this book most powerfully is none other than the polymath Robert Smithson, who is mentioned in every chapter. This is not surprising. After all, Smithson's theoretical writing on the picturesque and on the tradition of landscape, his challenge to the art museum in the form of earthworks and the site/non-site paradigm, and his influence on subsequent generations of artists make him a charismatic figure linking landscape, land art, and eco art. Yet, this reader finds herself wondering if his significance is not overstressed in Cheetham's pages. Perhaps this is my bias, but what makes Smithson more necessary to this history, which is clearly not a chronological account, than artists such as Ana Mendieta or even Andy Goldsworthy, neither of whom are mentioned? Cheetham makes no explanation of the artists he chooses to discuss or those he neglects, leaving the reader to wonder if the vast variety of work that falls under the category of eco art is even possible to address in one book. While enormously rich with artistic and philosophical examples, the book may prove a challenge to some readers because of its idiosyncratic structure. On top of the integrated examples that support each chapter are eight "dossiers" which Cheetham treats as "purposefully individual and thus not symmetrical in detail or methodological approach" (27). These mini-essays, on topics such as “deracinated trees,” “earth-death pictures,” “Indigenous landscapes,'” and “the crystal interface,” also include deep studies of particular works such as Michael Heizer's Levitated Mass (2012) and Roni Horn's Vatnasafn/Library of Water (2007). It is irritating that the publisher has chosen not to list these sections in the table of contents, as these discrete case studies would function nicely as teaching excerpts for the eco art history instructor. This formatting lessens the usefulness of the text as an overview for undergraduates, though it will certainly appeal to the graduate student seeking out examples of an ecocritical art historical approach and to the advanced scholar looking for an in-depth overview of the topic. With this book, as Cheetham explicitly states, he is contributing to a growing trend: eco art history. As a form of research and analysis that works to reveal and engender stronger relationships among art, science, and ecology and between the human and non-human, eco art history has its roots in the interdisciplinary environmental humanities. It is particularly indebted to the last few decades of ecocritical literary scholarship, a forceful subfield which has, through its engagement with many creative practices, from nonfiction writing and cinema to new media and art, fostered a large international community of scholars. Such organizations as the Association for the Study of Literature and the Environment (ASLE) and the Association for the Study of Literature, Environment and Culture in Canada (ALECC) have been active supporters of the genre. While the work of scholars such as art historian Alan Braddock and literary scholar Christoph Irmscher—co-editors of A Keener Perception (2009), one of the first edited collections of eco art history—are acknowledged by Cheetham, few other ecocritical scholars find mention in this book. This is disappointing, as the work of Greg Garrard, Ursula Heise, Catriona Sandilands, and Stephanie LeMenager could have enriched Cheetham's discussion of aesthetics, representation, and the role of the artist in raising questions about the current state of our planet. There is no question that ethics and responsibility haunt the ongoing discussions of how eco art can address such massive problems as climate change or the human right to clean air and water. Yet rather than focusing on the elements of activism present in eco art, as the art historian T.J. Demos has done in several recent books, Cheetham aims to focus on the “articulation” (11) of the environment through aesthetics. Cheetham's methodology deliberately privileges the affective importance of eco art, underlining its intrinsic value and its potential impact on the viewer's growing awareness of the interconnectedness of all living things, which he treats separately from art’s political implications. In “Case Study 3: Indigenous Landscapes–,” Cheetham makes an exception to this affect-oriented approach by emphasising the role of land and environment in the practices of Indigenous artists working in Canada, including Kent Monkman, Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun, Arthur Renwick, and Bonnie Devine. In his evocative prose, Cheetham explores the environmental commentary of these artists, who use a variety of techniques, from nineteenth-century picturesque to modernist landscapes, alongside Indigenous ways of knowing, to comment on the ongoing impact of colonialism on Indigenous and settler relationships to land. He also makes important reference to the current debates around settler-colonial art history and the place of the privileged art historian in addressing these histories, drawing on the work of Ruth Phillips and Damian Skinner, to argue for the inclusion of Indigenous artists within his largely Western art history of eco art. While he acknowledges his position as a settler art historian writing in Canada at the beginning of the book, and gives mention to the writings of scholars such as Loretta Todd, Cheetham leaves out from this section mention of the rich work of Indigenous ecocritical thinkers, missing an opportunity for a stronger interdisciplinary discussion of Indigenous knowledge and artistic practices. Cheetham's primary commentary on eco art is that, as a practice, it does not require an artist to be activist. Instead he believes “that it is an encouraging development that artists who do not portray themselves necessarily as environmentalists, and whose practices include a wide range of concerns, nonetheless address ecological issues with great acuity” (204). In an age of global crisis and environmental collapse, this argument may not fully convince or satisfy readers who wish for a more materialist or social art historical engagement with the ecological in art. Nevertheless, Landscape into Eco Art offers a thoughtful and historically grounded reflection on an important and growing practice in contemporary art, and its promotion of “ecological thinking.” Dr. Karla Kit McManus is Assistant Professor of Visual Arts (Art History) in the Faculty of Media, Art, and Performance at the University of Regina. --[email protected] Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|