|

Diana Sherlock, ed.

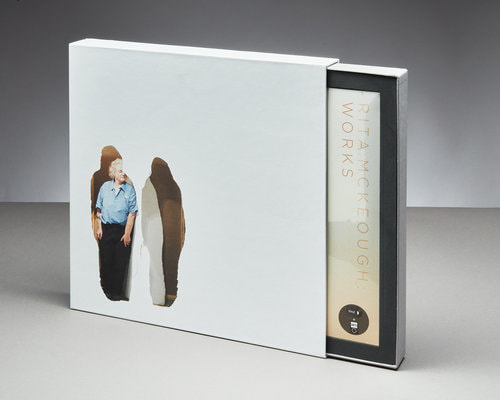

Rita McKeough: Works Calgary: EMMEDIA Gallery & Production Society; M:ST Performative Art Festival; Truck Contemporary Art in Calgary, 2018 162 pp. colour illus. $45.00 (hardback); $75.00 (hardback with 12-inch vinyl boxset); $280.00 (hardback with vinyl and limited edition art multiple). ISBN 978-09867369-2-6 Rita McKeough: Works is a substantial monograph spanning over forty years of the artist’s collaborative and performative multimedia works. Edited by Diana Sherlock and published by three Calgary artist-run spaces, it is a critical acknowledgment of the major productions of this leading Canadian contemporary visual artist whose installations address violence against women, human and animal relations, and environmental deterioration. Mirroring McKeough’s fierce feminist practice, thirteen texts bear witness to the collaborative process of layering very distinctive voices into a collection that nevertheless remains resolutely provisional. Rita McKeough: Works exists in three versions: as a standalone book, as a book with a vinyl record reworking five key soundtracks, and as a set including the book, the record, and a playful multiple: a carrot with its adoption certificate. Designed by Dana Woodward and printed by Friesens, the quality of the production is remarkable, from the rounded page corners that recall artists’ sketchbooks to the abundant colour illustrations, including a close-up of leaves enhancing the inside front and back hard covers, lifted from McKeough’s Veins, a multi-media installation that makes reference to the Alberta landscape (2016). This comprehensive monograph complements the many catalogues of single projects already published, such as Rita McKeough: The Lion’s Share (2012), Rita McKeough: an Excavation (1994), and Dancing on a Plate (2000). Over the years, McKeough’s oeuvre has held the attention of many feminist scholars such as Jayne Wark and Joan Borsa, to name a few, and her work is featured in broader feminist anthologies such as Caught in the Act: an anthology of performance art by Canadian women (2004) and Inversions: the female grotesque (1998). This monograph supplements personal evidence of her inclusive process through the voices of her collaborators, at the same time giving evidence of the importance of artist-run culture in the development of her practice. Thus, it significantly expands our understanding of a leading feminist artist, one who has also drawn the attention of authors of other types of thematic anthologies such as Alberta Art Chronicle: adventures in recent contemporary art (2005) or Oh Canada: contemporary art from North North America (2012). The foreword attests to the artist’s enduring impact and her contribution to the politics and ethics of artist-run culture. Vicki Chau (EMMedia Gallery and Production Society), Desiree Nault (M:ST Performative Art Festival), and Ginger Carlson (TRUCK Contemporary Art in Calgary) acted as publishers for the monograph, having also been co-producers of recent installations by the artist. This collaboration among artist-run centres was vital as none had the necessary resources on their own. In their foreword, Chau, Nault, and Carlson emphasize the need for spaces that make room for difficult conversations and marginalized voices otherwise swept under the rug of dominant narratives. The introduction presents a succinct summary of the book, and is followed by “Thinking Out Loud,” a sizable investigative exchange between Diana Sherlock and McKeough. As elsewhere in the book, the text emulates the artist’s practice by constructing a feminist space through the convivial exchange of ideas. The conversational space thus created allows for queer and gender-fluid identities and experiences. Moreover, the cordial tone is an invitation to all readers to join in, thus enacting the possibility of a more inclusive future. The following three essays and an additional conversation by former fellow collaborators Jude Major, Eli D.Campanaro, Deirdre Logue, and Cheryl L’Hirondelle give evidence of their participation in key works. This allows readers privileged access to very complex productions. Tellingly, their voices overlap when recollecting In bocca al lupo—In the mouth of the wolf (1991–92). This ninety-minute multidisciplinary opera made overwhelmingly visible the collective fear and trauma associated with patriarchal violence. A feminist tour de force performed five times around the country, it is rightly seen as a decisive deployment of queer genealogy in feminist performance art that is now informing the practice of younger generations of feminist artists. Mary Scott intervenes just past the middle of the book with “If I.” Scott is known for her polyvocal feminist reworking of language. Scott’s poetic text makes sure the reader is not getting too celebratory or comfortable in “(t)here.” Repeating words make their meaning unstable. “If I” is slippery. It slips, slips, and slips, and thus emulates McKeough’s insightful practice and process of making the familiar seem peculiar. Jeanne Randolph follows with a piece of speculative ficto-criticism set in 2084. Dr. Randolph’s “Dr. Doolittle’s Death Diary” aptly maintains the feeling of displacement enacted by Scott. Dr. Doolittle is the only human survivor of the end of the world. His journal recounts his delirious conversation with, among others, a salamander and a parrot. The colourful eccentrics concoct a parable of all that has gone wrong between human and non-human animals, echoing McKeough’s concerns, as expressed in several installations. This post-anthropocentric future is picked up by Johanna Householder, who forays into a discussion of two works: Long Haul (2006) and H (2013). Her text also signifies a shift towards broader analytical stances by the remaining authors. Long Haul and H gave agency to a robotic tree and a giant squirrel. In the first instance, the tree and the artist strolled the streets of Banff in amiable companionship. In the second, the robotic tree becomes the assistant of the giant squirrel running an emergency hospital for old or sick cell phones. Householder’s analysis shows how McKeough deploys these characters as capacious metaphors for aging and death, and as exemplars of the place of care and empathy. Anthea Black analyzes slipping by, an installation she organized with McKeough while working for Stride Gallery in 2005. This performative installation aimed at making viewers collectively aware of the paradox of capitalist time. On closing night, surrounded by sixty viewers, McKeough dangled disquietingly from the ceiling for sixty minutes, while sixty one-minute audio pieces marked the passing of the hour. The last two texts are by emerging critics Elizabeth Diggon and Areum Kim. Diggon discusses compassion, reciprocity, and humour as explored in tender (2015), a hospital for the rehabilitation of hot dogs traumatized by their previous fate. (The hot dogs were part of the artist’s earlier installation titled The Lion’s Share.) Kim examines Veins, the artist’s most recent work. The complex, immersive multi-media installation disrupts the logic that defines some as non-human by giving voice to all, and from shifting viewpoints. The only analysis missing from Rita McKeough: Works is an examination of the challenges facing transformative artists, such as McKeough, under our prevailing economic and political neoliberal conditions. To read a work critically one needs to see the underlying infrastructure that makes legible its aesthetics and political condition. In a few instances, the artist and a few authors briefly refer to the anthropologist Marcel Mauss’ notion of “the gift” but do not pursue an in-depth critical analysis of how the gift functions in a capitalist context. Similarly, the genuine circulation of deep love in the “bocca family” is very tangible; but love cannot shed a clear light on supporting infrastructures. This criticism does not diminish the book’s achievement of archiving McKeough’s manifestations of marginalized voices and her legacies of collaboration on such a comprehensive scale. On the contrary, it glaringly reminds us of the work that still needs to be done in order to make certain the feminist futures for which McKeough so fiercely wishes will remain in our reach. Mireille Perron is a visual artist, writer, educator, and founder of the Laboratory of Feminist Pataphysics (2000). She is Professor Emerita at the Alberta University of the Arts (formerly the Alberta College of Art and Design). — [email protected] Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|