|

David Smith

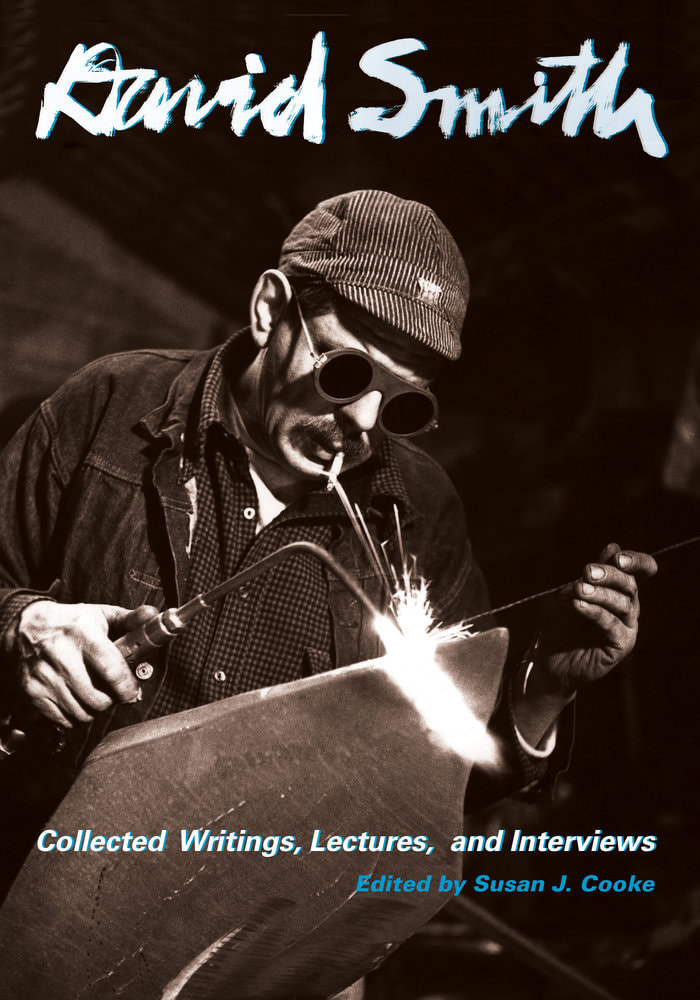

Collected Writings, Lectures, and Interviews Susan J. Cooke, ed. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2018 312 pp. 28 color photographs, 11 b/w illus. $38.00 (paperback) ISBN 9780520291881 Now that you’ve started reading this sentence, you can’t stop. This silly psychological fact would have annoyed David Smith had he lived to see this review, given the antipathy for art historians like me that repeatedly surfaces in this collection of his essays, lectures, interviews and occasional writings. “There is no true art history, no true appreciation,” he observes in a speech from 1960 (332). Expanding this complaint a few paragraphs later, he adds: "We have all let anthropologists, philosophers, historians, connoisseurs and mercenaries, and everybody else tell us what art is or what it should be. But I think we ought to very simply let it be what artists say it is. And what artists say it is, you can see by their working. I would like to leave it just like that." (333) For Smith, only art says anything worthwhile about art. The work speaks for itself. By contrast, with rhetorical tricks and gold-plated erudition, critics, historians, and curators distract the art-going public from the heart of the matter—the art—instead piling up irrelevancies like influence, biography, context, meaning, and stylistic analysis. Moreover, for Smith, this is about principle. That’s an ethical “ought” in the passage above (“[W]e ought to very simply let it be. . . ”). Art flows from individuals asserting or expressing themselves. Art historical bafflegab interferes with the right and obligation of artists to express who they are. As Smith writes in an essay from 1955, “The theory-laden historians’ truth-beauty calculations of past ages have no connection with us” (247). Sauve qui peut. Stop reading now. Or don’t: Smith hedged on this matter more than these excoriations suggest. While teaching drawing and sculpture at Sarah Lawrence College in 1950, he produced a typescript several pages long wherein he directs students to sympathetic bookstores, provides an annotated bibliography of books by and about artists like Hieronymus Bosch, Paul Klee, Pablo Picasso, and André Masson and, coming to his conclusion, lists among the “untold numbers of books you should have or should read” Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists along with Robert Goldwater and Marco Treves’s Artists on Art (94). And artists never outgrow the value of reading about art. In an interview from 1964, when he was in his late fifties, he said, “I love to read art books. I want to know everything that has ever been known by any man” (382). But that interview itself warrants a comment: it is the book’s longest and most generous conversation and its interlocutor is Thomas B. Hess, at the time among the United States’ most prominent art critics. And other art writers also appear in this volume in conversations with Smith, including dancer-become-dance critic Marian Horosko and Frank O’Hara, better known as a poet but seen here courtesy of his day job as the Museum of Modern Art’s assistant curator of painting and sculpture. Reading these interviews alongside the extensive question-and-answer sessions that often follow his talks, one gets the sense, despite Smith’s prickly message, that he is happy to discuss art historical and critical concerns. And the archival footage available online (such as the substantial excerpt from the O’Hara conversation posted on vimeo.com as “David Smith: Sculpting Master of Bolton Landing”) reinforces this impression, as does Smith’s interest in the literary activities of painters like Robert Motherwell (founding editor of the “Documents in Modern Art” series to which this book belongs) and Barnett Newman, a regular contributor to such mid-twentieth century small magazines as The Tiger’s Eye. Moreover, Smith appointed Clement Greenberg an executor of his estate (though he might have reconsidered had he anticipated Greenberg’s tampering with his sculpture’s colour).[1] Given this ambivalence, what should we make of this usefully expansive collection, which undoubtedly would have been even weightier had the artist not died in a car wreck at the age of 59? Perhaps (to invoke the heady discourse that Smith disdains) his dismissals of attempts to write about, explain, or describe art exemplify what Jacques Derrida memorably calls the pharmakon: writing as “both remedy and poison.”[2] For instance, the speech quoted above, titled “Memories to Myself,” comes from a conference organized by the National Committee on Art Education, sponsored by the Museum of Modern Art and featuring among its speakers Alfred H. Barr Jr. and Rene d’Harnoncourt, MoMA’s director of education and director, respectively. The event took Smith into the shark’s mouth, where he tries to protect art from writing by participating in the discourse that he decries. He sees the irony—the contradiction that twentieth-century dialectical materialism would have viewed as inevitable. He’s read his Marx, he assures Hess, and approbative references to Marx, socialism, and unions scattered through these writings support Smith’s left-wing formalism, a view espoused by influential commentators like Greenberg in “Avant-garde and Kitsch” (1939) and Theodor Adorno in “Commitment” (1962) that positions art’s autonomy as a bulwark against what it sees as capitalism’s inevitable attempts to manage our imaginations. Smith’s thought in some ways anticipates Donald Judd’s prominent writing of the 1960s: both artists developed their sculptural practice out of painting, and both therefore saw painting and sculpture as one discipline. However, Smith’s insistence on the need to overcome the paradox by which art never escapes instrumentalization, but ought to, links him not to late Modernism’s art as tautology but to the earlier form of art for art’s sake: high Romanticism and its commitment to art for the sake of a way of life. “Liberty—or freedom—of our position is the greatest thing we’ve got,” he tells David Sylvester in 1960 (317), replaying the mid-twentieth century equation of radical abstraction with autonomy that would become the object of landmark analyses by, inter alia, Serge Guilbaut, Eva Cockroft, and Jane de Hart Mathews.[3] Even more striking, perhaps, is this collection’s explicit display of the masculinism that Marcia Brennan, for one, has shown underpins mid-twentieth century formalism.[4] When, talking with Hess, Smith says he wants to know everything that any “man” has known, his use of the word “man” to mean any sentient, agential person is characteristic of this writing. But so too with his art, which he proudly says he welds himself (and so, much as he appreciates Picasso, he’s maybe more appreciative of Julio Gonsález, who did much of Picasso’s welding) and which became bigger and heavier throughout his career. Several times in this book, Smith discusses scaling up his practice of putting wheels under some sculptures by building a series of works on train cars. To Hess, Smith says, “I’ve sat on those goddam 4-8-4s welding them up, hoping that I could someday make sculptures as big as that” (379). An endnote observing that “4-8-4” designates the wheel arrangement of a type of steam locomotive, though right, stops too soon. Weighing close to 40 tons, this massive engine led passenger trains across North America at speeds approaching (or, on some reports, exceeding) 100 miles per hour. It epitomized brute locomotive power—almost certainly why Jeff Koons chose a 4-8-4 to star in the ill-fated 2012 proposal for his Train sculpture (a full-size model of the engine to be dangled above one end of New York’s High Line). What better, more manly, way to support his aspiration to build a sculpture the size of a locomotive than to refine his welding chops by building said fire-breathing monsters? However, this book goes beyond documenting and reflecting Smith’s era. For one thing, the judicious selection and chronological arrangement by Susan J. Cooke (who, as Associate Director of the Estate of David Smith, knows these archives well) shows Smith working to make his writing interesting—unlike Judd, for example—and avoiding the bathos that often plagues artists’ notes when they shade into poetry. For another, Smith’s interests in sincerity and monumentality still resonate (see his show at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in late 2019). And if his insistence on art as the site of liberty feels like so much ideological capture, surely that assessment flows at least partly from our current conviction that spectacle inevitably subsumes culture. Our time produces us as much as his produced him, and what he says through his work (as he would put it) doesn’t reduce to passive echoing of his era’s spirit. By assembling this collection, Cooke builds on the work of painter Cleve Gray and archivist Garnett McCoy, who edited anthologies of Smith’s writings forty-five and fifty years ago. Cooke exploits her access to superior archives to supersede those earlier collections, though her prefatory note remarks that most of Smith’s correspondence remains unpublished. It’s tricky ground. Increasingly, editors of such collections seek to be exhaustive (perhaps because current technology makes these projects easier than they once were). But I often wonder if the outcome repays the effort: not every scrap needs broad circulation. By contrast, Cooke seems to have selected representative samplings from across Smith’s three decades as a mature writer, which strikes me as usefully mirroring the skepticism with which scholars should approach all life writing: as a thoughtful friend once put it, such material isn’t nothing, but nor is it the final word. And, as Cooke says, those who need access to every last fragment can visit the archives. For the rest of us, this substantial reference volume usefully contributes to the historicisation of the 1950s and 1960s and to the fathoming of that era’s persistent chaos, never more profound than when it seemed most calm. Charles Reeve is associate professor in Liberal Arts and Sciences and Art at OCAD University and was president of the Universities Art Association of Canada/L’Association d’art des universités du Canada from 2016 to 2019. —[email protected] [1] Rosalind Krauss, “Changing the Art of David Smith,” Art in America 62, no. 5 (September-October 1974), 30–33. [2] Jacques Derrida, “Plato's Pharmacy,” Dissemination, translated by Barbara Johnson (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1981), 63–171. [3] Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom and the Cold War, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1983); Jane de Hart Mathews, “Art and Politics in Cold War America,” The American Historical Review 81, no. 4 (October 1976): 762–787; Eva Cockroft, “Abstract Expressionism, Weapon of the Cold War,” Artforum 12, no. 10 (June 1974): 39–41. [4] Marcia Brennan, Modernism’s Masculine Subjects: Matisse, the New York School, and Post-Painterly Abstraction (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2004). Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|