|

Martha Langford, ed.

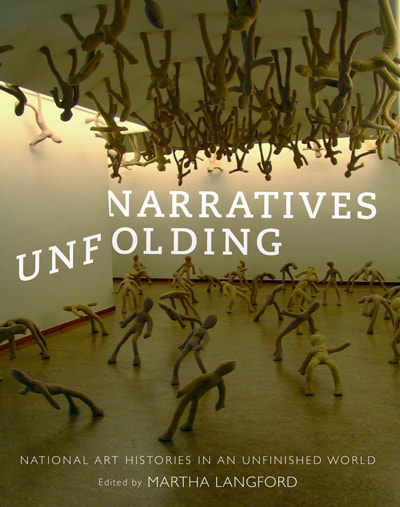

Narratives Unfolding: National Art Histories in an Unfinished World Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2017 437 pp. 100 colour illus. $39.95 (paper) ISBN: 9780773549791 $120 (cloth) ISBN: 9780773549784 Narratives Unfolding: National Art Histories in an Unfinished World is a complex collection of sixteen new essays that tackle the difficult and persistent problem of art history and its national frameworks. Unlike many critical anthologies that emerge as topical or thematic collections offering a divergent direction in a field, Narratives Unfolding presents a retrospective conundrum that lingers in the conjoined and overlapping fields of art history and visual culture since their disciplinary shake up in the 1970s and 1980s. Langford begins by naming the global as the “éminence grise” that has, for some time now, irreversibly complicated the relationship between the discipline of art history and the metric of nationhood. In this collection, the global is not conjured up as an artefact of recent history (post–1989). Instead, its beginnings are teased out in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as margin notes in a range of national art histories that are inherently modernist projects. As such, Langford has intentionally steered away from editing a volume that attempts to cover a global perspective, outlining instead the shortcomings of “global art” history and its orientalizing operations. Though the conference that preceded this collection took place in London in 2014, the resulting volume offers a broad compendium and seeks to renew discussions about the shortcomings of the globalized art world, which tend to remain ahistorical and embedded in the contemporary moment. Langford’s emphasis on national art histories telescopes in from the conditions of the global. The collection proceeds in a roughly chronological fashion, starting with the “unfinished” or latent features of nineteenth- and twentieth-century national projects, which sit uncomfortably in the present geo-political moment, and includes case studies from Turkey, Ireland, Scotland, Egypt, Israel/Palestine and Palestine/Israel. The second half of the collection concentrates on contemporary issues emerging from the ways in which contemporary art has performed its exchange value as a globalizing function over the last few decades. Narratives Unfolding assembles diverse case studies of modern and contemporary art, architecture, art history, and visual culture, and offers alternative geographies of art that deviate from the familiar, Western place-based narratives as singularly urban or national phenomena. Many contributions also address transculturation and decolonization as specific forms of circulation that move within and beyond the framework of the nation. Taken together, the essays in this collection trace complex relays in the decentralizing networks of the global that highlight local or “unorthodox” anomalies in national contexts, stories that, in Langford’s words, “could never take hold in national art-historical accounts, but really belong nowhere else” (35). This is where the collection becomes deeply compelling, but also where readers must work to suture connections between the historical and temporal points on an itinerary that, with a few exceptions, remains weighted toward the Global North. Langford’s introduction to the collection is a tour de force, highly valuable in its own right for artists, art historians, and theorists navigating the interstices of networked art history and the archives of modernism and contemporary art. She charts a labyrinthine history that goes between the historical foundations of national art histories in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the late twentieth-century projects of “world art history,” and subsequent global art histories and counter-histories after the Cold War. Throughout, she entertains a healthy suspicion toward the shortcomings of the turn toward global art histories and visual culture in the 1990s, a necessary turn that seems to have left the field in disarray. She points out that the “study of global art history can be taxed for its lack of historical distance” and cites a range of art-historiographic positions that emphasize the shifting “texture of experience” of microhistory (Mark Salber Phillips), as well as the macrohistorical ideas of “belatedness” and “anachronism” put forward by the art historian Keith Moxey (13-14). The crux of the collection seems, however, to be intergenerational, and revolves around “emerging scholars of national art histories” whose “relational” practices test the “equilibrium of the nation state” and “form fluid socio-political formations.” Here, contributions from Carla Taunton and Erin Silver engage settler-colonial histories and decolonial questions around the violence of the nation state that are currently at the forefront of Indigenous struggles for sovereignty in the Americas and world wide. In divergent ways, Johanne Sloane and Steve Lyons write of the difficulties in moving beyond the idea of the “avant-garde,” which is usually as located in specific formations associated with specific cities, while also performing specific cultural functions in the ways in which art history is written. In this Langford senses an urgency in the imperative to keep art history alive as a political project that resists the levelling effect of visual culture, while also remaining sensitive to the many forms of social justice that relational art practices activate. Reflecting on years of teaching and supervising art history students, Langford highlights a driving conundrum facing many graduate students: “They ask who will write these histories if I do not?” As we witness the rise of resurgent and reactive nationalisms worldwide, this collection seems to anticipate the question: Are we entertaining the notion of a post-global era? Like many academic books that went to press in late 2016 or early 2017, the carefully constructed positions around art history and nationalism are in conversation with an earlier phase of globalization that preceded the neo-nationalist spasms of Brexit and the election of Donald Trump. The positioning of the global in Narratives Unfolding indicates that globalization underpins the “unfinished world” alluded to in the subtitle of the volume, but here the global remains relatively under-theorized, or at least not as fully developed as theories of nationhood or nationalism. References to Homi K. Bhabha, Arjun Appadurai, and Benedict Anderson crop up throughout the volume, yet the mechanisms of the global are not always clearly in sight, despite their impact on the forms of political consciousness that are activated throughout the collection. Ideas about the global can be found, for example, in the essays by Beatty, Silver, Ilea, and Sigurjónsdóttir, which tackle transcultural translation or cultural negotiation of citizenship outside of national frameworks. This is not a shortcoming of the collection, but rather an indication that the relationships that exist between art history, visual culture, and globalization occur in an ambivalent nexus that is still evolving. I am a product of the academy of the 1990s, an acolyte of the ill-defined field of visual culture (which was denounced almost as quickly as it was named). Emerging from cultural studies, visual culture tends toward a fundamental mistrust of nationhood and singular identities, beginning at the margins with the rise of postcolonial theory and queer theory, to name only a few of the many disciplinary shifts that were taking place at the time. While art history and visual culture are intimately related areas of study, there are many unresolved tensions between the two fields, which this collection makes evident. Alice Ming Wai Jim’s essay on the “twinned visions” of Vancouver and Dubai, for example, performs the work of visual culture in its exploration of the uncanny repetitions of global portal cities. It is perhaps the outlier in this collection, as it activates an understanding of technologies of vision and spectacle as concepts necessary to parsing the work of the Vancouver-based collective Maraya. Where shifting borders and migration are concerned, as in the essays of Merav Yerushalmy, Inbal Ben-Asher Gitler, Ceren Özpinar, and Corina Ilea, the centrality of the artwork or archive under analysis in each case situates the analysis more firmly as “art historical.” I mention these essays in particular, because anthologies of visual culture frequently focus on migration and bordering practices as leitmotifs of globalization, and visual culture has often claimed this territory when art history has proven resistant to exploring extra-national or migratory concepts. But where visual culture begins and art history ends is perhaps a moot point. An emergent question from Langford’s introduction—again, the “unfinished world” that she invokes—concerns what visual culture might still achieve or activate. It is worth speculating much further on art history’s relation to the formation of modern nation states in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, while at the same time keeping in mind that visual culture and globalization share disciplinary origins in 1990s. The enduring connection between questions of territoriality (whether at the level of the globe, the nation, or the city block), visuality, and cultural production that binds this collection together suggests a beginning rather than an end. Lee Rodney is Associate Professor of Art History and Visual Culture at the University of Windsor. [email protected] Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|