|

Carol Zemel

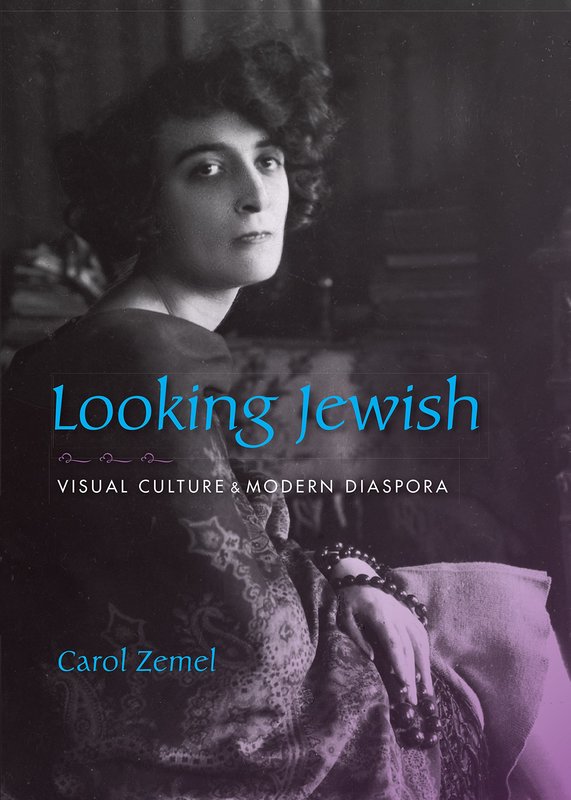

Looking Jewish: Visual Culture and Modern Diaspora Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015 216 pp., 72 b/w illus. $45 (hardback) ISBN: 978-0-253-01542-6 In her 1948 book A Short History of Jewish Art, Helen Rosenau, an art historian educated in Germany, but forced to flee the country in 1933 due to National Socialism’s persecutory policies toward Jews, discusses artists of the diaspora—the painful dispersion or scattering of the Jewish peoples—a reality Edward Carter draws attention to in his preface to her book. With respect to modern diasporic artists, Rosenau remarks, “The variety of these artists is such that it seems almost impossible to gauge any specifically Jewish traits…. However, in spite of the impact of their respective national schools, certain traits of abstraction, of individualization, of interest in personality and the moral content of the work of art survive, even with assimilated Jewish artists, and relate them to their own past history” (19). For Rosenau, cultures of the diaspora are sensitive to social change. She observes that, “in our own age the Jewish evolution enters a new and contrasting phase, confronted as it is with attempts of destruction in the physical sense, and by the problems of nationalism versus assimilation, and liberalism versus orthodoxy” (21). The problems Rosenau identifies feature significantly in Carol Zemel’s Looking Jewish, a thoughtful and sophisticated analysis of art and visual culture in the modern diaspora. For Zemel, diaspora refers not solely, or simply, to a displaced ethnic group living in a broader national milieu. Her aim is not to celebrate an ethnic art production, thereby rescuing Jewish artists from relative obscurity and elevating them to the modernist pantheon. Drawing on remarks about diaspora by the artist R. B. Kitaj, she outlines the term as referring to modes of living and working across two or more distinct, yet interrelated societies at once. This “working across” provides a means of resistance against conforming to “any conventional aesthetic or national style” (2). Modern diaspora therefore potentially constitutes an enabling dislocation, a form of opportunity to look beyond extant categories and positions, a promise to be explored. Diasporic identity is often conceived negatively as incomplete assimilation, yet this ambivalent status may also provide liberating aspects. Through her engagement with diasporic art, Zemel makes an important contribution to ongoing debates in diaspora studies about how to conceive and study diaspora. By way of the importance she accords art and visual culture of the diaspora as forms of social resistance, and also as a result of the attention she pays to ambivalence as a characteristic of diasporic identity, she positions herself alongside postcolonial thinkers such as James Clifford, Homi K. Bhabha, Franz Fanon, and Paul Gilroy. Zemel, however, differs from these thinkers, who have each influenced art history, in the sustained focus she accords to the visual as a locus of reflection upon diaspora. Looking Jewish is a work of art history that explores painting, photography, prints and other media. Because of its spirit of experimentation, as art history it merits being placed alongside endeavours such as Adrian Rifkin’s Ingres Then, and Now (2000), T. J. Clark’s The Sight of Death: An Experiment in Art Writing (2006), and Griselda Pollock’s Encounters in the Virtual Feminist Museum: Time Space and the Archive (2007). Its narrative is not straightforwardly linear, even if it is roughly chronological. It also does not track relations among artworks through a prism of categories including nation, style, or period. Zemel, rather, allows the concept of diaspora to travel within and across various periods and media. Looking Jewish performs something of the conceptualisation of the diasporic it ultimately elaborates, not straightforwardly accommodated within art history as it has been traditionally conceived yet all the more promising for this lack of ready fit. Zemel begins with an analysis of the photographers Alter Kacyzne and Moshe Vorobeichic, Jews from the Pale of Settlement, who were active in the 1920s and 1930s. Although Kacyzne and Vorobeichic took on very different projects—the former using pictorialist documentary to record a changing society and an emergent nationalism for a North-American audience, the latter employing modernist photomontage to foster nostalgia and distance in an international Jewish cultural elite—Zemel suggests that both photographers capture “the pride and ambivalence of modern diaspora consciousness and minority nationhood” (52). The second chapter considers the paintings, prints, and drawings of the Polish artist and writer Bruno Schulz. Schulz is best known for his Polish-language short stories; his art has received less critical attention. Zemel’s close reading of the play of gazes among a young Jewish man wearing orthodox garb, two women dressed à la mode, and the putative spectator in Schulz’s Encounter: A Young Jew and Two Women in an Alley (1920) enables her to tease out how the painting figures separateness and difference and the impact of a fast-changing world upon Jewish life in Galicia. Zemel also provides a sustained and powerful analysis of Schulz’s The Booke of Idolatry (1920–1922), a series of erotic prints in which the artist explores his desire for female domination. Schulz’s foot fetishism, already signalled in Encounter (in which the young Hasid, bowing, seems to focus particularly on the legs and feet of the women he passes in the alley) reaches its apotheosis here. For Zemel, however, The Booke of Idolatry is much more than a masochist’s “spank bank.” Her remarkable reading traces how Schultz uses eros and idolatry in the prints “to evoke the tensions of Jewish difference and accommodation at the same time” (67). Zemel argues that the tableaux stage an encounter between the individual and the social, embodying both private fantasy and social metaphor. The diaspora Jew’s social anxiety as it intersects with his masculinity registers through Schulz’s iconography, an iconography in which women disdain and ignore the men who form their entourage—a lack of acknowledgment between individuals that provides broader insights into the conditions of cultural subjectivity and of the realities of a subject requiring the recognition of an Other in order to be. The third chapter examines Roman Vishniac’s photographs of Eastern-European Jews, which were taken prior to World War II, but published in its aftermath as A Vanished World. These photographs, framed by the horrors of the Shoah, are conceived as a eulogy to the diaspora. For Zemel, the collection “presents a curiously costumed and pathetic people, a people without potency or agency” (102). This lack of agency places the images in stark contrast to many of the other case studies in Looking Jewish. Zemel’s focus “on images of Jews by Jews and for Jews” (2) frequently allows her to draw attention to agency as it manifests through diasporic cultural productions—the Jewish “look” being self-produced. This is evident, for example, in Chapter Four, which centres on representations that examine stereotypes of Jewish femininity, the Yiddishe Mama (the Jewish Mother) and the Jewish princess. Zemel considers how artists, including Eleanor Antin and Amichai Lau-Lavie, contest and subvert such stereotypes. Rhonda Lieberman and Cary Liebowitz’s Chanel Chanukah (1991), for instance, calls attention to the Jewish Princess and critiques the stereotype for the vacuous materialism it embodies. The chapter foregrounds Zemel’s sensitivity to gender issues, a sensitivity already signalled in Chapter Two in relation to masculinity, but here it involves a more expansive exploration of Jewish gender ideals. The final chapter examines diasporic values in contemporary art, focussing on three artists unified by their perceived use of allegory—R. B. Kitaj, Ben Katchor, and Vera Frenkel—as a means of providing a subtle and sophisticated engagement with how specific works think the nature of diaspora. The reading of Kitaj as an artist provocateur, whose paintings, at times, embody “the anxieties and uncertainties of diasporic emigration” (143) through complex interplays of style and subject matter and a de-forming of the figure, is particularly striking. Zemel demonstrates a rigorous and perceptive understanding of the painter’s craft, one likely honed through her earlier work on Vincent van Gogh, which permits her to attend insightfully to complex intersections of the ideological and the material in Kitaj’s work. Her sensibility towards paint as a means of meditation—towards paint as philosophy—lets Zemel investigate how Kitaj’s aesthetic articulates a vision of diaspora as unfixed possibility, as a source of both tension and pleasure. Through her readings of Kitaj, Katchor, and Frenkel, Zemel, as elsewhere in Looking Jewish, compellingly advances a notion of diaspora “not [as] a choice between separatism or assimilation, but instead [as] a more negotiated and changing space-between” (160). Community and home are conceived by these artists as negotiated and tentative. Zemel identifies a specifically Jewish experience of “disquiet, dislocation, disruption, and fear” operating within works by Kitaj from the 1980s. Specificities of Jewish experience, shaped by history and cultural tradition, were also recognized by Rosenau, who observed that “the spirit in which a subject may be approached is more important than the subject-matter as such” (pp.57–58). It is this spirit—a particular pictorial intensity, a characteristic excess—that enables Rosenau to perceive works by a Catholic convert, Anton Raphael Mengs, as retaining a Jewish look. For Zemel, Kitaj appropriates aspects of the formal vocabulary of modernist painting, embraces its aesthetic structures, yet also brings a supplementary intensity, a diasporic sensibility, to bear upon those structures. Other artists in Looking Jewish share this spirit of openness and innovation, one facilitated by feelings of dislocation generated by diaspora. Neither Rosenau nor Zemel regards such a spirit as unchanging. In their different ways, they both seek to describe the particularities of modern diasporic identity, an identity not given but continuously made and remade. Rosenau concluded her short history of Jewish art reflecting on how “a productive assimilation of … new values” might “lead to hitherto unseen expressions in artistic creation” (71). For Zemel, a similar promise—an as-yet uncharted journey—is in the process of emerging in the art and visual culture of the modern diaspora. Nicholas Chare is Associate Professor of Modern Art at the Université de Montréal, Diane and Howard Wohl Fellow at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and a member of the RACAR Editorial Board. Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|