|

Erin Morton

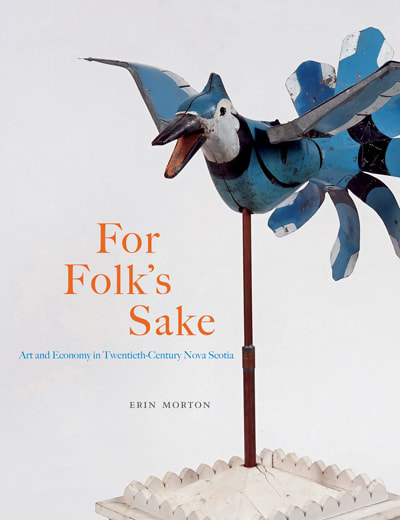

For Folk’s Sake: Art and Economy in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press/Beaverbrook Canadian Foundation Studies in Art History Series, 2016 424 pp. 76 colour illus. $ 108 cloth ISBN 9780773548114 $ 49.46 paper ISBN 9780773548121 For Folk’s Sake: Art and Economy in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia is a richly documented and beautifully illustrated exploration of folk art’s cultural ascendancy in Nova Scotia. Erin Morton draws from an impressive range of research to offer the reader a truly interlinked study of art making, cultural policy history, and economic development in the province during the second half of the twentieth century. The book is set against the backdrop of the 1950s, a “decade of development in tourism, technology, cheaply manufactured consumer goods, and infrastructure (plumbing, electricity, highway expansion)” (6). It tracks the shift from plentiful government funding of culture in the province around the centennial (1967) to increased private sponsorship, in line with broader, transnational restructuring trends in the 1980s. In the face of this change, Morton contends “many visual artists, writers, government bureaucrats, and tourism promoters produced nostalgic renderings of Nova Scotia’s past as its future charged forward” (6). For Folk’s Sake is set squarely within Nova Scotia’s transition to a neoliberal economy and makes a strong case for the myriad ways this form of late capitalism emerged—in this instance, through the institutionalizing of folk art by the province’s leading cultural agents (8). Morton explains that folk art in Canada has been implicated frequently “in particular nostalgias that long for a rural, settler-colonial Canadian past that heritage promoters, such as [Marius] Barbeau, largely constructed by denying the realities of capitalist expansion” (26). She draws extensively on the work of scholars like Lauren Berlant, whose focus on affect theory as it relates to temporality informs the book’s critical assessment of late capitalism’s nostalgic sentimentality for the past. Significantly, even as Morton situates For Folk’s Sake within national and transnational developments shaping public and academic ideas about folk art, she underlines the necessity of a critical regional exploration attending to local particularities. A focus on the tension in Nova Scotia over the past six decades between the self-taught and the schooled artist, on the interrelationship between those with the privilege of formal art instruction and those who have taught themselves, is embedded in Morton’s use of the term “folk art,” which she describes as “the cultural objects of ‘folks’ who have largely not received art instruction, but who nevertheless produce things that the art world values from an aesthetic and economic perspective” (5). Yet even as it engages with the economy and pedagogy of the fine arts, this book is a call for the emergence (dominance even) of folk art in Nova Scotia to be situated within histories of cultural and economic development in the province under late capitalism. The twinned contexts of art and economy work in concert throughout the book to make it a valuable contribution to scholarship across many fields. Morton rightly points out that, “just as the rhetoric of recession and crisis in capitalism and the reality of economic disparity have appeared in cyclical patterns, so too has the birth and death of folk art in public cultural institutions.” Given this, she traces patterns of folk art’s “emergences, retreats and appearances” in Nova Scotia’s cultural institutions to demonstrate “connections with moments of crisis in the expansion of both modernism and the reshaping of capitalist modernity itself during the second half of the 20th century” (10). To my earlier point, Morton reminds the reader that “the folk art category is the product of a present that is constantly in the process of becoming the past, a transitory instant that exists both in tension and in consort with modernity as the cultural experience of liberal and neoliberal capitalism” (10). For Folk’s Sake opens with two thorough introductory chapters setting Canadian folk art within North American modernisms, offering an overview of folk art’s emergence in Canadian public life (particularly through federal and provincial cultural policy structures), and outlining the author’s strategies for a critical assessment of Nova Scotia’s local particularities of modernist practices and folk-art enterprise (14). Following these chapters, the book is laid out in two sections: the first looks at the “complexity of folk art’s emergence in private collecting circles, art galleries, screen media, popular writing, [and] global corporate sponsorship”; while the second reflects on the “institutional control of artists’ intellectual property in Nova Scotia.” These two complementary approaches reveal the processes through which “some objects of everyday use in rural Nova Scotia communities made the transition into art-world aesthetic economies such as modernism, while others did not,” and trace the “competing rationales that dictated folk art’s ascendancy over the province’s cultural identity” (14). This approach draws on the work of Ruth B. Phillips and Christopher Burghard Steiner in Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds (1999), and uses it as a roadmap for discussions of shifting cultural value and authenticity. Section one, “Art Institutions and the Institutionalization of Folk Art,” focusses its attention on the “most influential pair of cultural institutions” in Nova Scotia in the 1960s–1970s: the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD) and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (AGNS). Provincial and federal funding for art education and museum development in Atlantic Canada was largely funnelled through them. Given this, Morton claims “artists, collectors and curators working within these particular art institutions helped to transform folk art from a material object of creative and economic importance in rural Nova Scotia communities to one worthy of fine art collection, display, presentation, and study in the province and beyond it” (4). Yet it is often the former legacy of folk art that resonates in the creative practices of many contemporary do-it-yourself Nova Scotia “crafters.” This first section looks at the relationship between professional artists being trained at NSCAD and self-taught folk artists supported by institutions like AGNS, as well as collectors such as US American art dealer, collector, and landscape painter Chris Huntington, who played a major role in developing a contemporary folk art field in the province (14). Two other chapters look more closely at the many social and cultural agents and institutions forming a network for the promotion of folk art within Nova Scotia and, more broadly, within art-world economies of folk art. This section includes an in-depth examination of federal, provincial, and corporate sponsorship of the arts in Canada from the 1960s to the 1990s, which constituted the larger sphere of influence in which these agents operated (including a whole chapter tracking changing cultural funding policies). Overall, section one lays bare the institutional actors and social agents most invested in discovering folk art at this time. Section two, “Maud Lewis and the Social Aesthetics of the Everyday,” offers a series of case studies of Marshalltown-based painter Maud Lewis (1903–1970). Morton suggests how Lewis’s work helped AGNS to negotiate global corporate sponsorship in the 1980s–1990s, a development that largely took place without the influence of Huntington or other private collectors (15). As such, she contends, “it is worth considering how Lewis’s march to the top” came about largely through public history projects (from the CBC and the National Film Board, for example) (177). This section also includes a critique of the “foundational mythology” of Lewis, which Morton argues was “anything but unified and consistent.” In Nova Scotia, public history slowly developed from a “model of cultural preservation for community social and economic betterment” to a heritage industry that “played an important role in the dramatic social and economic reorganization of late capitalism” (186). Thus, in order to illustrate the full transition of AGNS to neoliberalism, the chapters in section two analyze the gallery’s control of Maud Lewis’s intellectual property rights through the copyrighting of her work (15). These case studies address the preservation of the Maud Lewis Painted House and the establishment of the Maud Lewis Authority and explore the tension between community and corporate commemoration and preservation tactics. For Morton, these interpretations of Lewis “say much more about those who curated her image and the historical presents they were variously grappling with than about Lewis herself” (214). In this way, For Folk’s Sake is also a contribution to the emerging field of critical heritage studies and complements scholarship by cultural theorists, such as Susan Luckman, who write on the location of cultural work in the creative economy. The section concludes with a nuanced examination of how intellectual property copyright was useful for an increasingly neoliberal institution like AGNS, while less so for the artist herself, who frequently copied her images for sale in a tourist market (292). This book builds on a wealth of scholarship across many fields, among them folklore and material culture, art history, tourism, economic history, critical museology, political science, cultural studies, public history, heritage, and craft. The author cites the work of heavy hitters like James Clifford, Henry Glassie, Nelson Graburn, Griselda Pollock, Donald Preziosi, and Raymond Williams, while also including Canadian scholars Sandra Alfoldy, Ian McKay, Sandra Paikowsky, Kirsty Robertson, Ronald Rudin, and Anne Whitelaw, among others, in the comprehensive bibliography. A strength of this book lies in Morton’s ability to synthesize the work found in her sources, but particularly that of McKay, whose book The Quest of the Folk (1994) has informed most research in this area since the 1990s. Morton rightly claims her book builds on McKay’s work by looking at the second half of the twentieth century, while also shifting the focus from folk art within the discourse of tourism in the province to its “visual and material culture emergence in the fine arts world” (4). While For Folk’s Sake is replete with interdisciplinary research, there is little to no mention of craft scholarship as it intersects with—underpins, really—the use of folk art throughout. For this craft historian reader, its near complete absence means craft haunts the book, hinting at the stakes involved in choosing to address folk art partially through an art-historical lens, or attaching it to a fine-arts discourse, even for the sake of challenging the latter’s limits. Alternative approaches are found in craft scholar Stephen Knott’s book Amateur Craft: History and Theory (2015), which explores the same tension between amateur and professional makers through an explicitly craft lens, or in curator Sean Mallon’s unpacking of the term “traditional” within critical museology, which suggests ways of engaging with such laden terms. The book’s attractive layout, clear writing and generous amount of crisp, colour images make it a pleasure to read, while its content merits discussion in university and college classrooms. Erin Morton has argued convincingly for the ways “folk art has been as much a vehicle for historical fiction in Nova Scotia as it has been a source of both economic possibility and cultural sentimentality” (303). For Folk’s Sake: Art and Economy in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia explores the relationship between the past and present in the historical and ongoing framing of folk art in Nova Scotia to offer the reader a model of what historian Hayden White describes as an ethically responsible transition from present to future. Dr. Elaine C. Paterson is Associate Professor of Craft, Chair of the Department of Art History, at Concordia University, Montreal. Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|