|

Monique Brunet-Weinmann

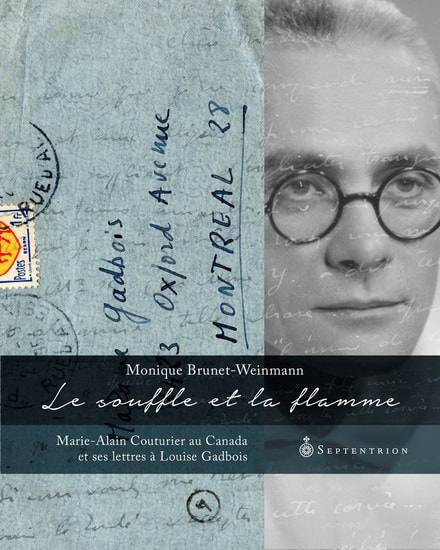

Le souffle et la flamme: Marie-Alain Couturier au Canada et ses lettres à Louise Gadbois Montreal: Éditions du Septentrion, 2016 336 pp., 33 colour illus., 42 b/w Paper $49.95 ISBN: 978-2-89448-865-2 This is a very complex book. At its core is the story of a fascinating man, a French Dominican monk named Marie-Alain Couturier, who was sent at the outbreak of World War II to the United States to minister, teach, and paint, and who moved mainly between New York and Baltimore, often in well-heeled and influential circles. Well known among Catholic intellectuals, he was invited to Montreal in March 1940 through the efforts of the philosopher Étienne Gilson. There, he renewed contact with the Montreal painter Paul-Émile Borduas, whom he had met at the Ateliers d’Art Sacré, which was founded by Maurice Denis and Georges Desvallières in Paris in 1929. Through Borduas and others, Couturier made the acquaintance of some of the major actors in the struggle for “l’art vivant” in Montreal, including the painters John Lyman and Alfred Pellan, the writer, critic, and teacher Maurice Gagnon, and the architect Marcel Parizeau. Soon recognized as a powerful ally against the rigid academic tastes and teaching methods of the art establishment in Montreal, Couturier played an important part in a modernist revolution of art in Quebec. Couturier also made the acquaintance of Louise Gadbois, a painter who was well respected as part of the “independent” group associated with Lyman and Borduas, and who was trying to balance her artistic ambitions with her role as a mother and hostess. Her comfortable Montreal home became a kind of oasis for Couturier over five turbulent years. As their friendship developed during that period and after, Couturier wrote to Gadbois. At the same time, she kept a journal, often reflecting on events mentioned in his letters. Le souffle et la flamme contains these letters, which have been well-annotated and published alongside selected passages from Gadbois’s journal. An extensive introductory and explanatory essay of over 170 pages precedes the whole. The complexity of this book has much to do with Couturier himself, who was a cleric often at war with conservative factions in the church; a supporter of General de Gaulle when such a stance was not appreciated among conservatives and Catholics in the United States and Canada; a practicing painter and expert in stained glass whose work appears in collections and buildings in Canada, France, the United States, and Europe; and a critic, curator, and artistic entrepreneur who had a real impact in several countries. Brunet-Weinmann wants to give the reader a sense of Couturier as an artist as well as an intellectual and agitator, and to give Louise Gadbois her due as an artist and facilitator (hence more than thirty pages of colour illustrations juxtaposing the artworks of the two). Couturier was much talked about in the newspapers of the time and in later histories, but he was also a rather mysterious figure, seen for a moment in Ottawa, Montreal, or Quebec, then disappearing for long periods. This book fills in the gaps, explaining his movements between Canada and the United States, where he was working on ambitious artistic projects as well as teaching. It also provides an important extension of that history, following him back to France after the war and showing how he encouraged great modern artists to return to sacred art, while also collaborating with the likes of Bonnard, Rouault, Braque, Lipchitz, Léger, Miro, and Matisse. Along with much new information about the man and his activities, Brunet-Weinmann gives pertinent discussions of Couturier’s art in which she shows, for example, the influence of El Greco (101) on his work, or analyzes his painting Chemin de la croix, which he created in the Elkins Park Hermitage in Philadelphia (105). Couturier’s letters to Gadbois also show a more intimate side of him as an engaging person often exhausted and discouraged by his activist battles and occasionally plagued by self-doubt. In spite of my admiration for this book as a source of new information on a fascinating man in a difficult time, I am bemused by an important section covering the 1945–1950 period. Here, Brunet-Weinmann’s tone and tactics change radically, and she inserts entire letters from Borduas, Fernand Leduc, and Jean-Paul Riopelle, all previously published in several books. Why are they here? The answer, it would seem, is to bolster the argument that Borduas and his younger, Automatists associates were hypocrites, previously expressing admiration for Couturier and then turning maliciously towards sabotaging his efforts to organize an exhibition of contemporary Canadian painting in France; their duplicity is to be matched only by the treachery of Maurice Gagnon and the shilly-shallying of the Quebec government in the person of Under-Secretary Jean Bruchési. One segment is actually entitled “Leduc contre Couturier: ‘Les Frères Ennemis?’” It is true that Borduas and the other signatories of Refus global, once widely condemned in Quebec, have, over the past fifty years, been increasingly lionized, written into the history of the “Quiet Revolution,” and treated as if they emerged suddenly to enlighten a dark world of religious and political repression, single-handedly dragging Canada into the world of contemporary abstract painting. Not surprisingly, there have been voices raised to question such oversimplifications, among them Jean-Philippe Warren. His book L’art vivant: Autour de Paul-Émile Borduas (2011) places Borduas in a historical context that includes Catholic intellectuals, and in which the thinking and writing of the Automatists were influenced by people such as Jacques Maritain and Couturier. Brunet-Weinmann’s book supports this general argument, while adding colour and personal detail. While I see these books as providing important nuance, I think they have a tendency to overstate the positive and understate the negative in their defense of the “personalist Christian” position. Concerning Couturier’s proposed exhibition, the documents Brunet-Weinmann provides actually show that Riopelle and Leduc had good reason to worry about a government-sponsored exhibition, and that their concerns about a priest’s involvement were understandable, given their connections with the anti-clerical surrealists in Paris. Meanwhile, back in Montreal, Borduas and Pierre Gauvreau were at first ready to collaborate with Couturier, and their eventual withdrawal was no denial of their early expressions of admiration for the man. Couturier, having returned to France with other fish to fry, didn’t suffer much from this event or others that followed in Quebec, but for Louise Gadbois things were different. Her close association with John Lyman and the Contemporary Arts Society (CAS) made her resent strongly what she saw as an attack from within by Borduas and his young friends. Unfortunately, almost a whole year (1947) of her journal has been lost or was unavailable to Brunet-Weinmann. Those pages might have shed light on some complicated events, including Borduas’ resignation from CAS and his break with Lyman, which was due mainly to the latter’s cool reaction to a first draft of Refus global. Brunet-Weinmann regards Borduas’ behaviour as disgusting, but she says little about the vehemence of the eventual attacks against him. Her judgement of Borduas as someone projecting his death wish onto others is as bitter as any I have read (p. 154), much harsher even than contemporary reactions against the manifesto, its author, and his young co-signatories—reactions that were often ferocious, patronizing, and occasionally downright silly. Brunet-Weinmann suggests that the missing year of Gadbois’ journal might have shown Couturier trying to “amoindrir les conséquences néfastes du manifeste” (158). In a similar vein, Robert Élie, Borduas’ friend and the author of the first important study of his work, published an extensive article entitled, “Au-delà du refus,” in the Revue dominicaine in 1949. Brunet-Weinmann sees this as a “très sérieux effort de conciliation entre les chrétiens et les artistes rebelles héritiers du surréalisme” (159); I see it as a condescending call to ignore Borduas’ writing (he’s a painter, after all) and to forgive his actions as misguided. For a view of Élie that Brunet-Weinmann does not provide, see Gilles Lapointe’s L’envol des signes: Borduas et ses lettres (1996), or Ninon Gauthier’s essay “Charles Delloye et la promotion des automatistes en Europe,” in Lise Gauvin’s collection Les automatistes à Paris: actes d’un colloque (2000). For the most comprehensive analysis to date of reactions to Refus global over the years, see Sophie Dubois’ Refus global: Histoire d’une réception partielle (2017). I could argue at length over details in Le souffle et la flamme while still being totally absorbed by it. The excerpts from Louise Gadbois’ journals give us a real sense of the social and artistic milieu of Montreal at the time as they centre both on this rather privileged class and a woman’s struggle to keep painting and maintain her confidence in the face of many other demands on her time and energy. I wish we had more of her writing. Admired as a portraitist whose influences included John Lyman and Philip Surrey, she was one of those painters who remained figurative while exploring modernist perspectives opened by Matisse and others. It is fascinating to see her artwork juxtaposed with Couturier’s, and I think the comparison is to her advantage. In the final analysis, however, what this book provides, through its emphasis on the very itinerant Couturier, is a broad view of art and artists in the context of national and international politics and artistic debates and developments over two continents at a crucial period of the last century. Ray Ellenwood is Professor Emeritus and Senior Scholar at York University in Toronto. Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|