|

Stan Dragland, with an appreciation by Michael Crummey

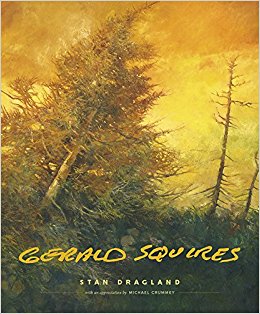

Gerald Squires St. John’s, NFLD: Pedlar Press, 2017 240 pp. 240 colour and b/w illus. $80 (hardcover) ISBN: 978-1897141823 Gerald Squires (1937–2015) was born in Newfoundland, but moved as a child to Toronto, where he received his early schooling and art education. A reluctant student at the Ontario College of Art, he dropped out to travel and self-instruct, and was successful enough to become an editorial artist for The Toronto Telegram in 1960, where he illustrated a column devoted mainly to local church architecture and news. Meanwhile, he was pursuing his researches in paint and ink, often exploring religious subjects in a style that was figurative, but certainly not realist, and probably best described as expressionist—a kind of fusion of figurative and abstract expressionism seen in the work of such painters as André Masson or the early Jackson Pollock. By 1965, he was gaining some important recognition: he won the Bronfman “Best Young Artist Award,” participated in group shows in Montreal, Hamilton, Ottawa, and Toronto, and had solo exhibitions at the Pollock and Helene Arthur galleries in Toronto. But 1965 was also the year he made a visit to Newfoundland with his family, which eventually led to a permanent return there in 1969. “Heading back to Newfoundland at the time he did,” Stan Dragland understates, “was no career move" (48). Indeed, it led to serious economic hardship for his family at a time when Newfoundland had little artistic infrastructure, but it also stimulated him to branch out and learn ceramics with his wife, Gail; to establish a studio for metal sculpture; to work on portraits, paintings, and sculpture commissioned by churches and public offices; and to take an active part in the astonishing ebullience in all the arts, throughout the island, starting in the late 1970. In a rather apologetic introduction to an exhibition entitled Painters in Newfoundland at Memorial University in 1971, curator Peter Bell opined, “Newfoundland may seem isolated, but away from snow-balling North American eclecticism, in a challenging and virgin landscape, the artist can find a new identity within himself.” Squires didn’t move to Newfoundland to escape artistic eclecticism, he had plenty of his own, but it is true he never showed much interest in geometric abstraction, pop- or op-art experiments, or the well-publicized and widely admired adventures into conceptual art that were all the rage at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax from 1967 to 1973 (satirized in a delightful 1987 film, Life Classes, by William MacGillivray, also Newfoundland-born with a mainland art education). Nor does he seem to have been tempted by the cool hyper-realism (hints of the metaphysical within the middle-class mundane) of Nova Scotia’s Alex Colville or Newfoundland’s Mary and Christopher Pratt, or the Gothic retrospection of David Blackwood, whose subjects are firmly based in Newfoundland, where he was born, although his professional life unfolded in Ontario. However much Squires may have liked and admired these fellow East-Coast artists, he certainly took a different route. Dragland sees him as a mystic in the great tradition of William Blake, a maverick like another tormented modern painter he admired: Francis Bacon. For Dragland, “[Squires] embraced the imperative to be who he naturally was, drawn to the sacred and out of step with his own secular time” (63). Despite a solid reputation in Newfoundland, Squires never caught on with those responsible for art museum collections on the mainland. He is not represented at the Art Gallery of Ontario, and he is barely present even in their library. The National Gallery of Canada has ignored him, though one of his works is in the Portrait Gallery of Canada (Library and Archives Canada). Exceptions to this indifference outside Newfoundland include the Confederation Centre Art Gallery in PEI and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, each of which has two works; York University, the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, and the McLaughlin Gallery also each have one work. It’s a sad state of affairs that makes Dragland’s book all the more important, because Squires is an eccentric and powerful artist who deserves to be more widely recognized. This book investigates Squires the visionary and the man more than it concentrates on art history and method. But there is, for example, a chapter devoted entirely to his imposing Cabot Tower, Signal Hill (1987), which compares different critical approaches to this surprising and complex painting, and there are others devoted to landscapes and portraits and places where the twain occasionally meet. The book is a generously illustrated volume of a size and quality that does the artworks justice, while also showing Squires’ wide range of techniques and materials, and illustrating the progress of an adaptable, community-oriented man whose intensely personal work reflects and affects his chosen environment. An important quality of his work is a tendency to create series in various media that involve themes of spiritual quest, sometimes but not always specifically Christian (Squires was raised as a Salvation Army Protestant, but was ecumenical in his interests), often stimulated by, or referring to, scriptural or poetic texts. Series based on the Canticles of St. John of the Cross and the writings of St. Francis of Assisi were among his early works shown in Toronto in 1966, and the inspiration found in Christian texts can be seen in drawings related to the Book of Job as early as the 1960s and as late as the Legend of Job (2015). These works exhibit Squires’ graphic skills, often in ink or gouache on paper, and depict human figures in an undefined, not entirely figurative context that suggests their suffering, doubt, and isolation. There is an obvious connection in theme and tone between these early works and the later Wanderer series (ca. 1969–71), with its semi-abstract, lonely humanoid figures moving through an empty, abstract landscape, as well as the Boatman (1976) and Cassandra (1983) series, in which the specific geography and history of Newfoundland are not so much depicted as suggested by ghostly references to landscape, sea, and boats. From the late 1970s to the end of his life, Squires produced related groups of paintings, such as the Ferryland Downs Series, a series of landscapes made using mostly acrylic on canvas and paper to depict rocks, barren land, vegetation, and tangled roots—what Dragland calls “seemingly representational landscapes” (134) charged with symbolic and spiritual meaning. In a neat reversal, Dragland argues that these more “accessible” paintings actually demand more of the viewer: Squires is still looking for what is hidden; it’s just that the surfaces, the likenesses, are now a closer match for what others see. That means they are not as challenging to the viewer as a Squires once was, or not in the same way. Some of the power of the unexpected, the grotesque, the amalgam of disparate elements, is also gone. More onus now rests with the viewer, to see into the fascinating surfaces of these later pictures, to reckon the continuing interplay of dark and light in them (120). This book has all the trappings of a conventional monograph on an artist, including an illustrated chronology of life events, movements, and exhibitions. But Dragland puts an unusual emphasis on Squires’ own writing when analyzing the paintings and drawings. There is plenty to work with. Squires not only sketched on any available surface, as do many artists, he also kept irregular journals with written and drawn accounts of his memories, visions, random thoughts, and quotations from philosophers and poets both ancient and modern, along with drafts of letters to a variety of correspondents, including Beelzebub. These journals and related “table scraps” have been made available to Dragland for the preparation of this book, as well as for a future, annotated edition of the writings themselves, on which he is currently working. At one point in the book we read, “[Squires] did set down quite a lot over the years, and he occasionally reached a certain eloquence, particularly in prose, but his natural instrument was the brush, not the pen” (88), a nuanced praise that I think undervalues Squires’ writing, judged by the samples that Dragland himself provides. In fact, for me, references to and illustrations of written and sketched journal entries and “table scraps” constitute a major attraction of this book. Gerald Squires is published by a small press best known for high-quality books mostly devoted to literature. And Dragland is best known as a writer of fiction, essays, and book-length studies on a variety of Canadian topics. He is Alberta-born, lived most of his professional life in Ontario, and decided to move to Newfoundland in 1997. If you wonder why he did such a thing, read Strangers and Others: Newfoundland Essays (Pedlar Press, 2015), where he explains his fascination with “The Rock” and confronts the vexed question of identity and belonging from a variety of angles, being a CFA (Come From Away) himself and living in a place where such people are often viewed with suspicion. Out of that fascination have come strong personal friendships in the literary, academic, musical, theatrical, and visuals-arts communities of Newfoundland with people such as Squires and Michael Crummey, the well-known poet and fiction-writer responsible for the “appreciations” at the end of this book. It’s obvious from the opening chapter that Dragland’s study of Gerald Squires relates to the “Strangers and Others” motif. Throughout the book, local belonging and community are crucial issues. In the Stations of the Cross and Last Supper, commissions done for Mary Queen of the World Parish Church in Mount Pearl (near St. John’s), Squires depicted very clearly, not only the Newfoundland environment, but familiar faces, many based on friends and acquaintances. He did many portraits, official and unofficial, in various media, of politicians and academics, writers and performers, family and friends, which were shown in public places or kept in the pages of his “Book of Souls” (portraits of people he liked or admired, 1986–2014). His public art graces church walls, St. John’s airport (Caribou on the Barrens, oil on canvas, 2002), the post office in Paradise (Winged Torso, a large, semi-abstract welded steel figure, 1977), and the woods of Boyd’s Cove (Spirit of the Beothuk [Shanawdithit], a life-size, realistic bronze statue, 2000). And his interdisciplinary interests are shown in his many collaborations with local writers and musicians. I was pleased to see an almost full-page review of Gerald Squires in the Globe and Mail (July 8, 2017). Such events are becoming more and more rare in the Globe, so Tom Jokinen’s comments were certainly welcome, but I had to smile at his comment that Dragland’s text is “a bit academic in places.” It’s not easy to deal with a widely read artist whose paintings and titles, journals, letters, and scribbled notes are filled with references to the Bible, Bertrand Russell, William Blake, Dylan Thomas, Rainer Maria Rilke, Yeats, Descartes, John Donne, and many others. It’s fascinating for the reader to watch Dragland struggling to come to terms with that tangled web, and well worth the effort, in my opinion. Ray Ellenwood is Professor Emeritus and Senior Scholar at York University in Toronto. Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|