|

Andrea Kunard

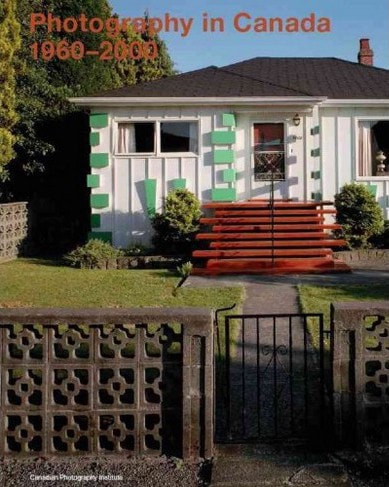

Photography in Canada 1960–2000 Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 2017 175 pp. 179 colour and b/w illus. $49.00 (paper) ISBN: 9780888849489 This catalogue, like the exhibition it accompanied, presents photographs from the National Gallery’s (NCG) collections made by individuals born, living, or having lived in Canada. Published under the auspices of the NGC’s newly formed Canadian Photography Institute, the catalogue is a much-needed survey of art photography in Canada. Each of the seventy-one, double-page catalogue entries, which are alphabetized by artist’s name, offers a short biography, a note on the artist’s place in Canadian photography history, and interpretive comments on the works reproduced. Each entry features a full-page reproduction on the right-hand page, accompanied by smaller reproductions. The entries are bookended by a historical essay and endnotes. The catalogue strives for clarity, balance, and equal representation, and avoids lionizing particular artists. Despite some shortcomings, it deserves consideration as an affordable, portable, and accessible panorama of Canadian art photography for the general public and for students. There were four previous volumes in the NGC’s photography series on modernist, French, British, and American photography. Each identified its corpus with the subtitle “from the National Gallery of Canada,” thus laying no specific claim to definitive or exhaustive coverage. That subtitle belongs on this volume as well, since a little more than half of the catalogued works are from the former Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography (CMCP), which evolved out of the Still Photography Division of the National Film Board (NFB). The remainder consists of works acquired by the NGC itself. Based on the acquisition information available in the book, this seems to exclude recent donations David Thomson made to the Canadian Photography Institute. Each work is identified by title, physical description, measurements, and reference number. Acquisition information is supplied where relevant, but incomprehensibly, the original collection is only indicated for works reproduced at a smaller size. The layout and typography, which is pretty much set in stone for the whole series, distinguish the various items of description lumped in the top left corner, but sometimes these conventions are lost on the reader. For example, the entry for David McMillan (cat. 50), born in Dundee, Scotland 1945, is a photograph entitled Winnipeg, Manitoba 1979. The juxtaposition of the two dates and place names is perplexing to the eye, until the brain resolves the confusion. A small vertical space between the two lines of type would have been helpful. The introductory essay attributes the origins of art photography patronage and collecting in Canada to the NFB and the NGC, under the respective tutelage of Lorraine Monk, Executive Producer, and James Borcoman, Curator of Photography. Arguing that little aesthetic activity was happening outside camera clubs prior to the 1960s, Kunard downplays the foundational role of turn-of-the-century pictorialism across the country, as well as the importance of independent artistic milieus, such as Montreal’s bohemia, which provided the Still Photography Division with many valuable, experienced contributors. She sketches the activity of the Still Photography Division up to 1967, then turns her attention to James W. Borcoman, who was tasked initially with collecting high-quality international work. The artistic concerns of the 1970s—pop art, conceptual art, intermedia, and critical approaches—worked against the fine-arts tradition of museums, but Kunard shows that both institutions tried to catch up with the trends in photography, championing photomontage, installations, feminist, and post-modern works well into the 1990s. Traditional topoi of photography, such as landscape and documentary, eventually returned, albeit in a more critical way that questioned environmental issues or the nature of representation. Although photographic artists all across Canada have been animated by critical social concerns in recent decades, Kunard singles out those from Quebec in relationship to the nationalist project—a relevant but limited approach. The catalogue entries mean to portray a “singular and culturally rich history” (11). The artists chosen are predominantly male (three quarters); those born in Canada mainly come from Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia, giving little exposure to artists from the Prairies and the Maritimes. Artists from outside the country are primarily from the United States. More than half of the artists were born right after World War II and came of age during the 1970s, getting attention for their work while they were in their thirties. The decade of the 1960s is the least well represented, and we may infer that this reflects the current critical fortunes of the early years of the Still Photography Division. Even though there was a great deal of activity at the Division, the work collected at that time is not as well regarded by critics today (and the NGC was itself mainly collecting high-value, international photography at the time). Readers with an interest in photography will recognize quite a few names among these entries: Edward Burtynsky, Michel Campeau, Fred Herzog, Yousuf Karsh, Michael Snow, Jeff Wall. The last, perhaps because of his fame, is not given biographical details. This inconsistency obliterates his evolution as an artist, and consistency is a cardinal virtue of this book. Other well-known figures include Raymonde April, Lynne Cohen, Donigan Cumming, Evergon, Pierre Gaudard, Tom Gibson, Michel Lambeth, John Max, Nina Raginsky, and Sam Tata. The notes expand on the essay and the entries, and do a good job of providing the reader with core references and further readings, though some take shortcuts. For instance, on the subject of pop art’s attitude towards photography as a reproducible ready-made, Kunard notes briskly, “Up to this point, photographs were seen mainly in magazines” (170, note 17). The hordes of Canadians with family albums and boxes of slides may silently beg to differ. Readers interested in the long history of vernacular photography in Canada should consult Lily Koltun’s Private Realms of Light: Amateur Photography in Canada 1839–1940. Finally, Kunard does not provide an index, nor is there a single-page list of all the photographers, as is common practice for group exhibition catalogues. Those two tools would have helped the reader to fully grasp the breadth covered here. For the first time in print, the period covered in this catalogue is presented as historical and not contemporary. Recent books, such Martha Langford’s Scissors, Paper, Stone: Expressions of Memory in Contemporary Photographic Art (2008) and Penny Cousineau-Levine’s Faking Death: Canadian Art Photography and the Canadian Imagination (2006), considered a large cross-section of the works Kunard addresses to be contemporary. Although not surveys of Canadian photography per se, both are wide-ranging and richly illustrated scholarly studies that treat half of the artists Kunard discusses under their respective frameworks of memory and imagination. Martha Hanna’s catalogue Confluence: Contemporary Canadian Photography (2003), while more modest in scope, is Kunard’s most direct predecessor. A joint project between the NGC and the CMCP—prior to the latter’s dissolution into the former—it also defined the national locus of photography as the sum of the two institutions. Offering a more comprehensive selection than Hanna, but limited to the NFB corpus, Kunard’s true ancestor in form and coverage is Martha Langford’s Contemporary Canadian Photography from the Collection of the National Film Board (1984). The two books have forty artists in common. Retrospective rather than historical, Langford’s book was published on the eve of the creation of the CMCP out of the Still Photography Division. With more than a hundred full-page reproductions, Langford’s “Blue Book” summarized the intense activity of the 1960s and 1970s at the NFB. It was a capstone to the NFB’s photo-stories, exhibitions, catalogues, and installations, as well as the latter’s IMAGE series of books and the 1967 Centennial publications, Call them Canadians, Stones of History and Canada: A Year of the Land. Going further back in time, The Banff Purchase (1979), though not an NFB endeavour, was another important, lavishly printed catalogue of a major acquisition of contemporary Canadian photographers by the Banff Centre that marked the rise of a new generation of artists also included in Kunard’s catalogue. Readers who wish to have a larger picture of Canadian photographic history would do well to search for the photography books newly referenced in artexte.ca’s online catalogue, or look at contemporary anthologies, such as Robert Bean’s Image and Inscription: An Anthology of Contemporary Canadian Photography (2006). Despite the presence of some photojournalism, photographs outside the artistic sphere are not well covered in Kunard’s survey, something she and Carol Payne attempted to do more explicitly in The Cultural Work of Photography in Canada (2011). Likewise, Payne’s The Official Picture: The National Film Board of Canada’s Still Photography Division and the Image of Canada, 1941–1971 (2013), still the only major published study on the topic, considers the Still Photography Division more for its impact on Canadian identity than as an artistic powerhouse. Like all surveys, Kunard’s book makes the reader hungry for more. Such a superbly and generously illustrated catalogue of Canadian photographers has not been seen in print for almost thirty years. The value of the book in disseminating photography goes without saying, and it is nice to see the artists being paid proper respect through good production values (200 lines per inch halftone, thick semi-gloss paper, sewn binding). The prepress is also free from the mistakes that plagued some reproductions in earlier volumes of the series: look for example at an over-sharpened scan of W. Eugene Smith Spanish Wake (cat. 55) in American Photographs 1900–1950 from the National Gallery of Canada (2011). Kunard’s book does not reach the stratospheric heights of specialized publishers’ photographic reproductions, but it goes quite above commercial standards, notably in the reproductions from black and white, the warm-toned ones in particular. The title may allude to this book being a follow-up to Ralph Greenhill’s seminal Early Photography in Canada (1965); it is not, by a long shot, but it is a volume waiting to be put on the reading list of an unfortunately still-hypothetical “History of Photography in Canada” university course. Michel Hardy-Vallée is a PhD candidate in the Interuniversity Doctoral Program in Art History at Concordia University. Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|