|

Sarah Milroy and Ian Dejardin, eds.

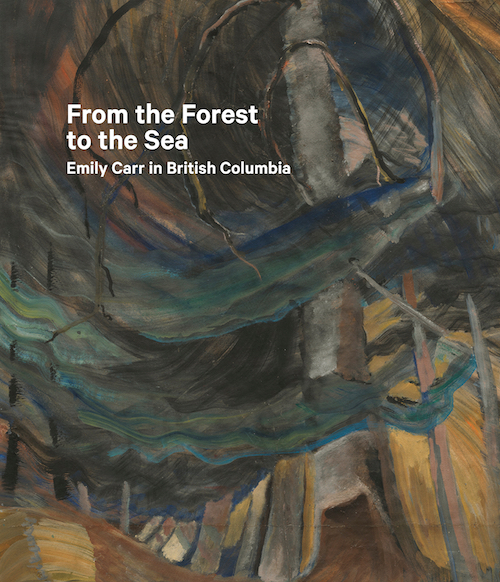

From the Forest to the Sea: Emily Carr in British Columbia Toronto, ON; London, UK; and Fredericton, NB, exh. cat., 2014 304 pp., colour illustrations $39.95, ISBN-13 978-1-894243-77-3 The catalogue From the Forest to the Sea: Emily Carr in British Columbia was published to accompany the exhibition of the same name organized conjointly by the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London and the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto and co-curated by the Toronto art critic Sarah Milroy and Dulwich’s director Ian Dejardin. It reproduces more than one hundred colour reproductions of Carr’s work, which it brings in dialogue with about the same number of images of historic Native art of the Northwest Coast. The volume focuses on the years after Carr’s participation in the Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art: Native and Modern (1927) and presents her as an artist channelling the influence of her homeland and its Native peoples. Building on the success of Painting Canada: Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2011, this exhibition and catalogue introduced Emily Carr to the British public as Canada’s next major national icon, an artist who manifested – as the Group of Seven had – the stark forms and abundant colours of Canadian modernist landscape painting. The Art Gallery of Ontario had the harder task of presenting “seemingly familiar works with fresh eyes” (11): Carr has had more national retrospectives than any other artist in Canada, the most recent in 2006.[1] From the Forest to the Sea attempts to offer a new look at Carr’s work by pursuing a political agenda that reveals a specifically Canadian sensibility built upon a diversity of voices, while still addressing the country’s colonial history. The custom of juxtaposing Native objects and Canadian landscape painting goes back to the National Gallery’s 1927 Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art: Native and Modern, which post-colonial scholars have roundly criticized for its appropriation of Native design for a nationalist purpose.[2] Carr nonetheless emerged from this exhibition as a nationally important artist. At the same moment, Native art was being appropriated by white Canada as a patrimony. After her death in 1945 and the first national retrospective that followed a few months later, Carr was said to be the mediator between the Canadian settler society and the Native peoples of British Columbia. It was not until 1990, when Carr’s third national retrospective, organized by the National Gallery of Canada, was met with a First Nations protest at Oka, that her supposedly deep understanding of First Nations culture – as promoted by her own writing (Klee Wyck, 1941) – began to be questioned.[3] It then became impossible to ignore Carr’s settler colonial identity, and scholars such as Marcia Crosby[4] and Gerta Moray subsequently raised questions of appropriation and assimilation of “Indian Design” in Carr’s work. Moray was the first scholar to link Carr’s ethno-artistic project of creating a complete pictorial record of Native villages with international primitivism, though she differentiated European practices from Carr’s direct contact with and address of the social realities of her own province.[5] In her monumental 2006 monograph Unsettling Encounters: First Nations Imagery in the Art of Emily Carr, Moray unfolded the socio-historical and settler colonial reality behind Carr’s production of “Indian Images” and considered the roles of Canadian ethnography, Christian missionaries, and wider political circumstances as well as Carr’s ambitions as a woman in Canada’s modernist art scene. From the Forest to the Sea clearly builds upon Moray’s groundwork by focusing on Carr’s rootedness in the B.C. land in the presence of First Nations material culture: in their effort to develop a better and more nuanced understanding of Carr’s relationship with British Columbia, the editors state that they intend to “encourage a discussion of Carr’s engagement with Indigenous art and the paradoxes of the colonial imagination” (12). For example, in her introductory article “Why Emily Carr Matters to Canadians,” Milroy tells the history of Alert Bay (‘Yalis) from the nineteenth century onward, in order to provide a specific illustration of the deep effects of the Indian Act and the Canadian residential schools system. Milroy reads Carr’s interest in First Nations people and culture during a time when they were most repressed as a protest against “the inhumanity of the colonial project” (37). The catalogue contains introductory essays by the two curators on Carr’s life, work, and importance for contemporary Canada. These are followed by six sections that mirror the configuration of the exhibition. The editors have ensured that the perspectives of contemporary B.C. artists, representatives of First Nations peoples, and scholars from art history and anthropology have been integrated into the chapters: “In the Forest” (James Hart, Jessica Stockholder, Robert Storrie), “The Modern Moment” (Gerta Moray, Charles Hill, Marianne Nicolson), “Drawing and Experimentation” (Ian Thom), “A New Freedom” (Peter Doig), and “Out to the Sea, up to the Sky” (Karen Duffek, Kathryn Bridge). The section “Trying to understand,” which focuses on Carr’s contact and engagement with Indigenous peoples, is the only one without scholarly essays. While the volume covers various aspects of Emily Carr’s oeuvre including her use of photography (Hill), her pictorial strategies in representing the vast B.C. landscape (Stockholder), and her influence on international contemporary artists (Doig), its emphasis through its structure, illustrations, and writing lies on Carr’s relation to Native peoples of British Columbia. Milroy’s introductory essay asserts that Carr’s work was grounded in a veritable will to understand Native cultures, and that her merging of local experiences and international influences has made her a role model for contemporary B.C. artists such as Jeff Wall, Damian Moppett, Christos Dikeakos, Liz Magor, and Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun. Carr’s influence and persisting importance as a local heroine is reinforced in subsequent essays by contemporary artists Corrine Hunt, James Hart, Jessica Stockholder, and Peter Doig. Milroy’s interview with Kwakwaka’wakw artist Corrine Hunt provides an Indigenous perspective within the catalogue’s introductory section. Hunt asserts that First Nations people still fight the conception expressed by Carr and her contemporaries of an idle and dying Native society. This misconception can only be fought, she says, by listening to voices such as Haida hereditary chief and contemporary master carver James Hart, who explains in his essay “The Tow Hill Pole: Emily Carr’s Totem and Forest” that Carr’s painting Totem and Forest (1931) actually depicts the house frontal pole of Hart’s forefather in the village Taaw Tlaagaa. Although Carr might have lacked knowledge about these monumental wooden sculptures and their meanings, Hart does acknowledge her sensitivity to the materiality of the totem pole, made of the same red cedar as the woods that surround it. The catalogue reproduces images of nineteenth-century objects including miniatures, amulets, rattles, bowls, and feast dishes, predominantly from the Tlingit/Tsimshian and Haida Nations, distinctive in their simple but expressive formline design. The works shown in the gallery space and presented in the catalogue were drawn from public and private collections in British Columbia and Great Britain. The curators seem to have chosen them for what they saw as a resonance between the aesthetic or spirit of the objects and Carr’s paintings, and for their capacity to bridge the colonial past and the lived reality of First Nations people (Carr had no direct experience with any of them). In his essay “Ambiguity in Northwest Coast Design,” Robert Storrie, an anthropologist and former curator at the British Museum, points to settler cultures’ difficulty in understanding Northwest Coast design. He argues that the objects used during the great feasts (potlatches) resist the orthodox classification methods used in typical ethnographic collections. Most of the time, he contends, we even lack an adequate vocabulary to describe either their form or their meaning. Marianne Nicolson’s and Karen Duffek’s close reading of objects may lead to new insights. By explaining the meaning and use of the Weather Dance Mask during the weather dances of the Kwakwaka’wakw people, Nicolson highlights Northwest Coast First Nations’ dependency on favourable weather conditions for fishing and harvesting (and she jumps forward in time to discuss the threat global warming poses for Native economic survival). Duffek explains that Nuu-chah-nulth objects such as the Wahling Harpoon Head (Takamł) always stand for and are embedded in a wider cultural context than the ones from which they were taken, and that they function as markers of detachment and connection at the same time, “inseparable from an ancient and still vital cultural complex specific to the inheritance, territories and values of the Nuu-chah-nulth people” (260). The central chapter of the catalogue, “The Modern Moment,” focuses on the years 1928–30 and features Carr’s iconic female figures such as Guyasdoms D’Sonoqua (c. 1930) and Totem Mother, Kitwancool (1928). The paintings are juxtaposed with a selection of expressive and colourful ritual masks from the Northwest Coast and with commentary from Gerta Moray and Charles Hill as well as Marianne Nicolson. Moray asks us to acknowledge Carr’s mission to reconcile Canadian settler and First Nations people through art, even though Carr sometimes misunderstood Native culture profoundly and accepted the settler conception of the First Nations as an expiring race. She suggests that by fusing post-Cubist techniques with the motifs of traditional pole carvings, Carr was able to portray the affective qualities of the colonial encounter with the Native totem poles, qualities that can also be found in the drawings and sketches of the B.C. forest that took the place of Native subject matter in her late work. In his chapter on Carr’s works on paper entitled “Drawing and Experimentation,” which presents an extensive selection of Carr’s charcoal drawings of the years 1928–33 and of her brush drawings executed between 1938 and her death in 1945, Ian Thom, Senior Curator at the Vancouver Art Gallery, identifies two major shifts in Carr’s post-1927 work: firstly, she changed her medium from watercolour to charcoal – allowing her to give her forests greater weight and volume –, and secondly, she began to use oil paint thinned with gasoline on manila paper – which offered her the speed of watercolour but with stronger colours, supporting her move away from object-centred imagery and toward a more atmospheric one. A complementary essay in the last chapter of the catalogue by Kathryn Bridge, archivist at the Royal B.C. Archives in Victoria, draws special attention to Carr’s thirteen sketchbooks, which contain more than four hundred images in pencil, charcoal, and watercolour from her travels, her study of books, and her museum visits. Bridge considers these indispensable for scholars wishing to understand not only Carr’s change of style, subject, and media, but her work as a whole. While the sketchbooks on display in the exhibition and reproduced in the catalogue show that drawing was for Carr a means to understand her environment, there is no in-depth discussion of her practice of copying forms and motifs from ethnographic books and collections that can be seen in the sketchbooks. Carr’s 1920s production of pottery and rugs in Native designs is missing altogether. Instead, the authors of the catalogue focus on her wider respect for the First Nations peoples of British Columbia and discover in her work the attitude that would become indispensable for a settler culture such as Canada to adopt in order to overcome its colonial past. From the Forest to the Sea can be credited with inviting the reader to see Carr as based in a place shared by Native and settler colonial peoples. The catalogue devotes as much space (in both text and image) to Native objects as to Carr’s works, and the small-scale Native items (ceremonial as well as domestic), enlarged and set against black or white backgrounds, sometimes surpass in their expressiveness even Carr’s monumental red cedars, totem and house poles, canoes, and other figures. (In the exhibition spaces, in contrast, these objects were grouped together in display cases and placed centrally in the rooms; and spectators, turning their backs to the showcases to study the paintings, risked overlooking them, although those who used the audio guides in the exhibition would have learned more about them.) In the evident concern for what the two organizing institutions called “cultural diplomacy” between Canada and England, the artists’ artist Emily Carr threatens, at moments, to disappear. The curators skim over the impact on Carr of her years abroad – particularly her studies in Paris and Brittany in 1910 with Harry Phelan Gibb – which makes it difficult for them to fully explain Carr’s fascination with the artistic production of First Nations people. It would be worthwhile to investigate Carr’s affective relationship with Native art of the Northwest Coast of British Columbia on an international scale. We can pick up where the catalogue leaves off and imagine new possibilities for thinking about Carr’s highly individual modernism with its specifically regional content together with the discourses of international primitivism. This is essential in order to do justice to an artist whose body of work shows its full complexity only when examined in relation to European modernism as well as locally. Elisabeth Otto is a Ph.D. candidate in art history at the Université de Montréal, where she is currently working on a dissertation on Emily Carr and Gabriele Münter. [1] Curated by Charles C. Hill, Johanne Lamoureux, and Ian M. Thom, Emily Carr: New Perspectives on a National Icon was presented at the National Gallery of Canada (2006) and then travelled to Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal, and Calgary. [2] For an extensive discussion of the 1927 exhibition and its critical reception, see, for example, Charles C. Hill, “Backgrounds in Canadian Art: The 1927 Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art: Native and Modern,” Emily Carr: New Perspectives on a Canadian Icon, exh. cat., National Callery of Canada, Ottawa (Vancouver, 2006), 92–121; and Leslie Dawn, “Northwest Coast Art and Canadian National Identity, 1900–50,” in Native Art of the Northwest Coast: A History of Changing Ideas, ed. Charlotte Townsend-Gault, Jennifer Kramer and Ḳi-ḳe-in (Vancouver, 2013), 304–12. [3] See Gerta Moray, “Exhibiting Carr: The Making and Remaking of a Canadian Icon,” and Charles C. Hill, “Backgrounds in Canadian Art: The 1927 Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art: Native and Modern,” in Emily Carr: New Perspectives on a Canadian Icon, ed. Charles C. Hill, Johanne Lamoureux, and Ian M. Thom, exh. cat. (Ottawa and Vancouver, 2006), 259–79. The 1990 retrospective was guest-curated by Doris Shadbolt and coordinated by Charles Hill. [4] Marcia Crosby, “Construction of the Imaginary Indian,” in Vancouver Anthology: The Institutional Politics of Art, ed. Stan Douglas (Vancouver, 1991), 268, 276–78. [5] Gerta Moray, “Wilderness, Modernity and Aboriginality in the Paintings of Emily Carr,” Journal of Canadian Studies 33, 2 (1998): 43–65; and “Emily Carr and The Traffic in Native Images,” in Antimodernism and Artistic Experience: Policing the Boundaries of Modernity, ed. Lynda Jessup (Toronto, 2001), 71–94. Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|