|

Félix Nadar

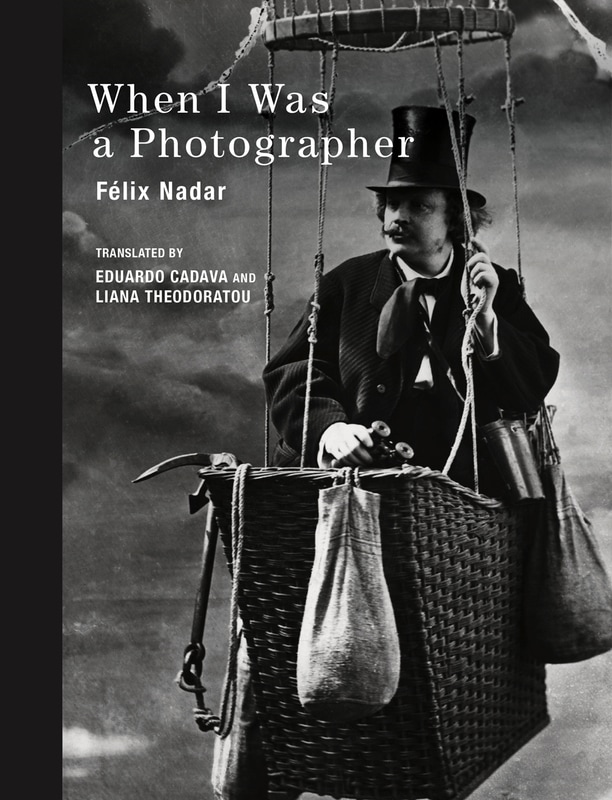

When I Was a Photographer Trans. Eduardo Cadava and Liana Theodoratou Cambridge, MA and London, UK: The MIT Press, 2015 336 pp. loth $25.95, ISBN 9780262029452 eBook $18.95, ISBN 9780262330701 As the nineteenth century ended, the same seemed to happen to Félix Nadar’s life in photography. Having sold his Marseilles studio in 1899, he published Quand j’étais photographe (“When I Was a Photographer”) in Paris the following year, and an image from 1909 reinforces the sense that he has quit photography.[1] It shows him seated at a large table, pen in hand, examining us deliberately if not unkindly, with no camera in sight. Apparently, his work has shifted from photography to literature. However, since Nadar took the picture himself, it unsettles the pastness of the book’s title. As Eduardo Cadava notes in his introduction to this lively rendering—the book’s first complete translation into English—Nadar never stopped taking pictures, so the title “figures his death by anticipating it” (xiii). Or, as Rosalind Krauss suggests in “Tracing Nadar,” a sensitive account of the awkward amalgam of science and spiritualism that influenced Nadar, maybe this “curious” title signals that photographers, like photography, had morphed from astonishing to unremarkable.[2] Perhaps Nadar wants to recover the “universal stupefaction” provoked only fifty years before by what he called that era’s “most astonishing and disturbing discovery” (2–3). Given the competition—Freud, Darwin, steam, electricity, anaesthesia—privileging photography in this way might seem excessive. But one purpose of When I Was a Photographer, which comprises thirteen anecdotes rather than a single autobiographical narrative, is to highlight photography’s psychological impact. By freezing the world, photography captures things that our eyes miss. The camera trumps the eye, with effects that explode in Nadar’s fourth chapter, “Homicidal Photography:” a young woman dies because “PHOTOGRAPHY wanted it…” (53). The incident concerns a wife who, having betrayed her husband, is dragged into abetting her lover’s murder. However, instead of the acquittal usually produced by such cases, this one ends with the crowd demanding the wife’s death and the judge, in what Nadar calls stupefying intellectual poverty, agreeing. The difference, Nadar argues, is photography’s intervention: [T]he service of the Prefecture has photographed the horror [of the battered corpse pulled from the water], and a devil of a journalist, always on the lookout, gets hold of the first print: since yesterday, people have been swarming the newsroom of Le Figaro, and all of Paris will pass by there. (51) Photography, as Nadar says, pronounced “the sentence without appeal: DEATH!” (51). And herein lies photography’s interest for Nadar, elucidated slightly differently by each of this book’s episodes. Though the advances of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, and William Henry Fox Talbot captivated him, the improvements, phenomena, and effects that encircled photography once it emerged fascinated him more, including aerial and subterranean photography, which he invented, and microfilm, which he helped advance. And the bizarre fantasies that photography prompted also gripped Nadar, such as Honoré de Balzac’s notion that photography diminished one’s physical being. Many nineteenth-century trends intersected at photography and thus, since he was one of that medium’s most energetic adherents, at Nadar. The self-portrait (c. 1865) on this book’s cover nicely captures this position: Nadar floats in a balloon’s gondola, looking into the distance (or the future), right hand clasping binoculars while his left clutches a rope for balance. Although staged in Nadar’s studio,[3] the picture stresses the value he put on photography’s complicated intersection with flight: as he recounts in “The First Attempt at Aerostatic Photography,” his efforts produced not even “the suspicion of an image” until he realized that balloon gas was spewing onto the photographic plate, interfering with the chemistry, and developed a work-around (64–67). So too in Paris’s sewers and catacombs, or during the Franco-Prussian War, each new context requiring more ingenuity from Nadar, and each instance of ingeniousness getting its own delightful (there is no other word) treatment here. Nor did Nadar limit his intercessions to science and engineering. He knew the landscape painter Charles-François Daubigny, buying two pictures from him in 1859. More famously, in April 1874, he hosted the first Impressionist exhibition in his rooms on the Boulevard des Capucines.[4] Moreover, Nadar illustrated, published caricatures, and wrote prolifically.[5] By the time of Quand j’étais photographe, he had authored numerous books including, forty-five years earlier, another compendium of episodes, Quand j’étais étudiant.[6] Thoroughly familiar with his epoch’s literary world, he referenced Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Black Cat” in his account of photography as homicide (the perpetrators and accusers, Nadar says, need “to strike at the wall of Poe’s cellar from where the denouncing meowing will come out” [50]) and channelled Poe in his use of overly formal prose to, paradoxically, energize his narrative. He knew Honoré Daumier and Charles Baudelaire, affectionately skewering the latter in an early caricature.[7] Yet Nadar was not alone as a nineteenth-century artist-cum-literatus. In fact, life writing by visual artists specifically had a “moment” in the years just prior to Quand j’étais photographe, the diaries and autobiographies of Maria Bashkirtseff, Adrian Ludwig Richter and William Powell Frith attracting considerable interest, and excerpts from what became Paul Gauguin’s Noa Noa appearing in La Revue blanche in 1896.[8] And while Nadar does not mention any of this literature, it is hard to imagine that he did not know of Bashkirtseff’s book, and perhaps the others as well. He certainly knew of the interest in artists’ life writing since he twice mentions (favourably) his association with Léopold Leclanché, both times identifying Leclanché as the translator of Benvenuto Cellini’s Vita (13, 143). Given this pre-existing interest in artists’ life writing, and Nadar’s fame and story-telling verve, I am mystified that Quand j’étais photographe, as Krauss says, sank without a trace in 1900. Perhaps this edition will garner the attention Nadar’s memoir deserves. Not that others have not tried. Krauss’s article was an afterword of sorts for Thomas Repensek’s translation of the book’s first three chapters in October (which raises another mystery: why stop there?).[9] More recently, Stephen Bann’s “‘When I Was a Photographer’: Nadar and History” nicely frames the way Nadar’s writing positions photography within an awareness of the impact this invention would have—Bann’s point being that one only can take account of Nadar’s photography by considering how Nadar himself took account of photography.[10] But for the most part, discussions of Nadar’s work at best mention his writing only in passing, thus distorting our picture of his cultural contribution. This book’s corrective fits into broader patterns of recovering not only the active literary lives of nineteenth-century artists but also photography’s trajectory during that time from miraculous to commonplace. It fleshes out our understanding of Nadar, of the astonishment that greeted photography’s birth, and of the vigour with which visual artists participated in the late nineteenth century’s literary culture. In general, this book performs these functions well, which is not surprising given that Eduardo Cadava, a Professor of English at Princeton, has written two books on photography, and New York University’s Liana Theodoratou has extensive experience rendering complex French texts into other languages. However, a few disconcerting slips do appear. One concerns Nadar’s description of the academic system as “this St. Helena,” which a footnote oddly claims alludes to the site of Napoleon’s exile (yes) and to his “role in creating a Salon des Refusés…in 1863” (uh, no) (256). And a later footnote again elides uncle and nephew, stating that “Napoleon” granted composer Jacques Offenbach French citizenship (258). These slip-ups make me wonder if further problems mar this generally engaging, useful project. Still, the overall level of care that Theodoratou and Cadava accord Nadar’s exploits and writerly verve makes When I Was a Photographer valuable for anyone interested in photography or nineteenth-century French culture—or, in fact, just a great read. Charles Reeve is an art historian at OCAD University in Toronto and president of UAAC/AAUC [1] Félix Nadar, Quand j’étais photographe (Paris, 1900). [2] Rosalind Krauss, “Tracing Nadar.” October, 5 (Summer 1978): 29–47. [3] Maria Morris Hambourg et al., Nadar (New York, 1995), 110. [4] Ibid., 237, 254. [5] Ibid., 10–14. [6] Félix Nadar, Quand j’étais étudiant (Paris, 1856). [7] Hambourg, Nadar, 60. [8] See Wayne Andersen’s introduction to Paul Gauguin The Writings of a Savage, trans. Eleanor Levieux (New York, 1996), xi. [9] Félix Nadar, “My Life as a Photographer,” trans. Thomas Repensek, October 5 (Summer 1978): 6–28. [10] Stephen Bann, “‘My Life as a Photographer’: Nadar and History,” History and Theory, Theme Issue 48: Photography and Historical Interpretation (December 2009): 95–111. Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|