|

Lora Senechal Carney

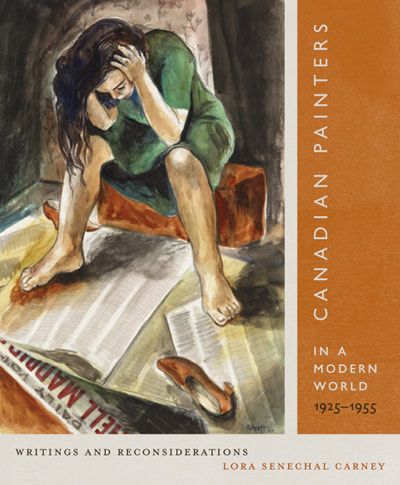

Canadian Painters in a Modern World 1925–1955: Writings and Reconsiderations Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017 352 pp. colour illus. $120 (cloth) $44.95 (paper) ISBN: 9780773551152 Lora Senechal Carney’s Canadian Painters in a Modern World 1925–1955: Writings and Reconsiderations is an extensively researched work and a valuable addition to Canadian art history. The book consists of a selection of primary source texts, reprinted artworks, and photographs, which Carney has framed with contextual narrative essays. The author has pored over thousands of letters, newspaper and magazine articles, reviews, private journals, and artists’ statements to carefully select primary sources that illuminate the artistic developments and discourses in Canada from 1925 to 1955. These writings are organized into eight chapters that address the artworks, as well as the public and private lives of specific artists, including Lawren Harris, David Milne, and Emily Carr, while also revisiting the socio-cultural context of the Spanish Civil War, the Second World War, and the early Cold War and their impact on artists in Canada. In the texts that introduce each chapter, Carney reflects upon how artists’ writings, art criticism, and personal correspondence constitute “a gathering of evidence of [artists’] perspectives on the issues that mattered to them” (xxvii), whether they be aesthetic, social, or political. The book is organized chronologically. It begins with Lawren Harris, focusing on the artist’s changing attitude toward Europe and its influence in the world. The first reprinted primary source is a little-known review, published in 1926 by Harris in the Canadian Forum, which considers Romain Roland’s book on Mahatma Gandhi. Harris sets Ghandi and Europe in moral opposition, praising the former’s non-violent policies as a counterpoint to Europe’s own colonial ones. What becomes clear from the selection of writings by Harris and others included in this chapter is that, for Harris, Canada and North America’s quest for a sense of nationhood is quite separate from Europe’s and is rooted in the spiritual. The following year, Harris shifted his position, defending recent artistic developments in Europe. As he argued in a review of the 1927 Société Anonyme exhibition presented at the Art Gallery of Toronto, the abstract paintings on view were “emotional, living works, and were therefore capable of inspiring lofty experiences; one almost saw spiritual ideas, crystal clear, powerful and poised” (29). The reprinted sources indicate that Harris, like Emily Carr and others, was searching for and trying to articulate what it meant to be a modern artist in Canada in the 1920s and 1930s; they also demonstrate how he used the language of Theosophy and spirituality as a means of establishing his approach to modern aesthetics. The following chapter, “Discovering David Milne,” reveals the important support Milne received from Canadian philanthropists Vincent and Alice Massey, as well other Toronto-based artists, while he persevered with his practice despite his isolation from the urban centre, working away in Six Mile Lake, Ontario. Chapter Three focuses almost exclusively on Emily Carr’s journals in an effort to “understand the course of her spiritual life,” and “her quest to find God” in both art and life (63). In the reprinted excerpts, Carr comes across as a less self-assured artist than Harris, but one who, like her Ontario peer, was driven by a deep need to express herself through art and to articulate her spiritual search in this regard. The last five chapters of the book are broader in scope. The author’s examination of the Spanish Civil War in Chapter Four offers a collection of writings that address “how individual artists and critics saw their roles in the growing crisis [of the Spanish Civil War]” (97). There was no consensus as to whether artists had a moral duty to respond to world events, and the well-known debate between Elizabeth Wynn Wood and Paraskeva Clark is here given more context with writings from both English and French Canada, including an excerpt from Walter Abell’s Representation and Form: A Study of Aesthetic Values in Representational Art (1936), the first book on aesthetic theory published in Canada. In the chapter “Defending Art vivant in Montreal,” Carney brings to life the story of how modern art slowly advanced toward the boiling point in wartime Montreal. While she claims this story is well-trod territory, the narrative is less familiar to those unable to read the French-language art history and primary sources of this period. While Montreal (and Quebec) were more open and generally more accepting of international and European artistic styles than English Canada—as the reprinted texts demonstrate—this chapter is a reminder of the constraints felt by Montreal artists in the face of the Catholic Church. The Automatistes (discussed in Chapter Seven) would, of course, throw off these shackles, and Carney’s narrative and choice of source documents in her chapter on this well-known group reasserts their importance and avant-garde status in the history of Canadian art, while also revealing the international connections developed by many members, such as Paul-Émile Borduas, Jean-Paul Riopelle, and Françoise Sullivan. Chapters Six and Eight focus on the Second World War and the Cold War. They examine the responsibility many artists felt with regards to democracy and politics, and chart their responses to wartime. Carney includes here texts by writers such as Robert Ayre and Walter Abell, as well as Pegi Nicol MacLeod’s account of her involvement with the Women’s Services, during which she painted women in the armed services in the 1940s. Chapter Eight examines how artists including Alex Colville and Miller Brittain grappled with an entrenched sense of fear as the Cold War era dawned; excerpts by Jack Shadbolt, Alexandra Luke, and Jock Macdonald, the manifesto of the Plasticiens, and a piece by Guido Molinari provide a sense of the changing attitudes to art and culture into the 1950s. The book includes numerous high-resolution reproductions of artworks and photographs that will be new to most readers. Carney does little, however, to analyze and connect these images to her claims about the artists and their social context, leaving the task of critical analysis to students and scholars of historical Canadian art. Carney’s book would have been strengthened had she laid out her selection criteria in more detail—not just in terms of the primary source texts she reproduces—but in her choice of artists for stand-alone chapters. Why do Harris, Milne, and Carr warrant their own chapters, while other modern artists—including Pegi Nicol MacLeod, John Lyman, Paul-Émile Borduas, and Paraskeva Clark—do not? Carney’s choices reinforce the notion that Harris, Milne, and Carr—three artists who have arguably received some of the most attention in Canadian art history—might be the most important of their day. Canadian Painters in a Modern World 1925–1955: Writings and Reconsiderations will be of particular use to those teaching Canadian art history at the post-secondary level. Since the publication of George Fetherling’s Documents in Canadian Art in 1987, there have been few easily accessible volumes with primary source material for scholars of Canadian art history. That Carney has put these writings into context and offered a narrative framing device for each chapter is of great benefit for those trying to engage new and current generations of students learning about historical Canadian art. The book is written in accessible prose and a general public with a vested interest in historical Canadian art will find within its pages anecdotes and new perspectives on well-known figures like Harris and Carr, while Carney’s assessment of the social aspects of the period under examination offers new insights into hitherto overlooked material and gives a strong sense of changing viewpoints, atmosphere, and artistic developments in Canada. Devon Smither is Associate Professor in Art History/Museum Studies at the University of Lethbridge. Vertical Divider

|

|

|

|||

|

|